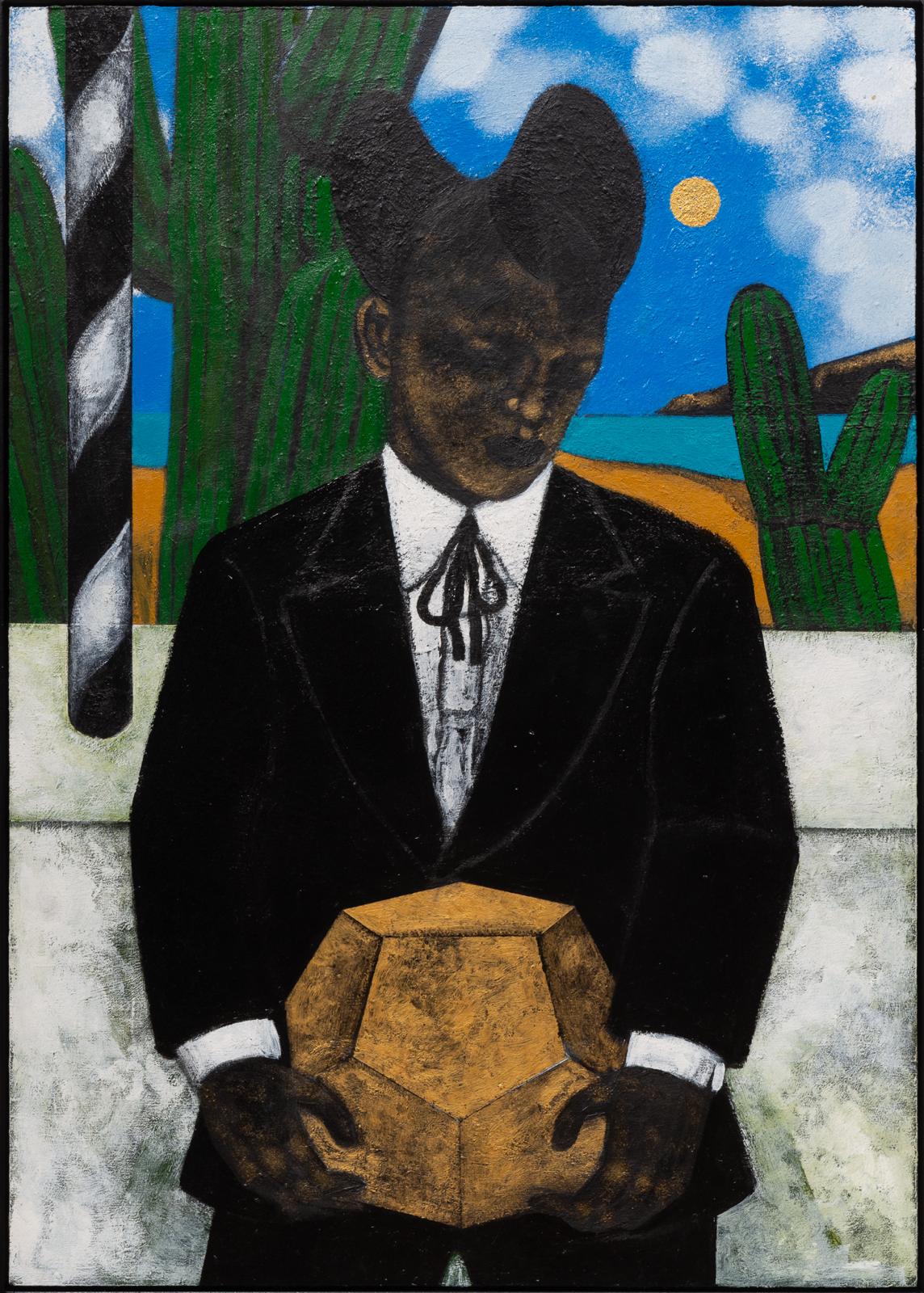

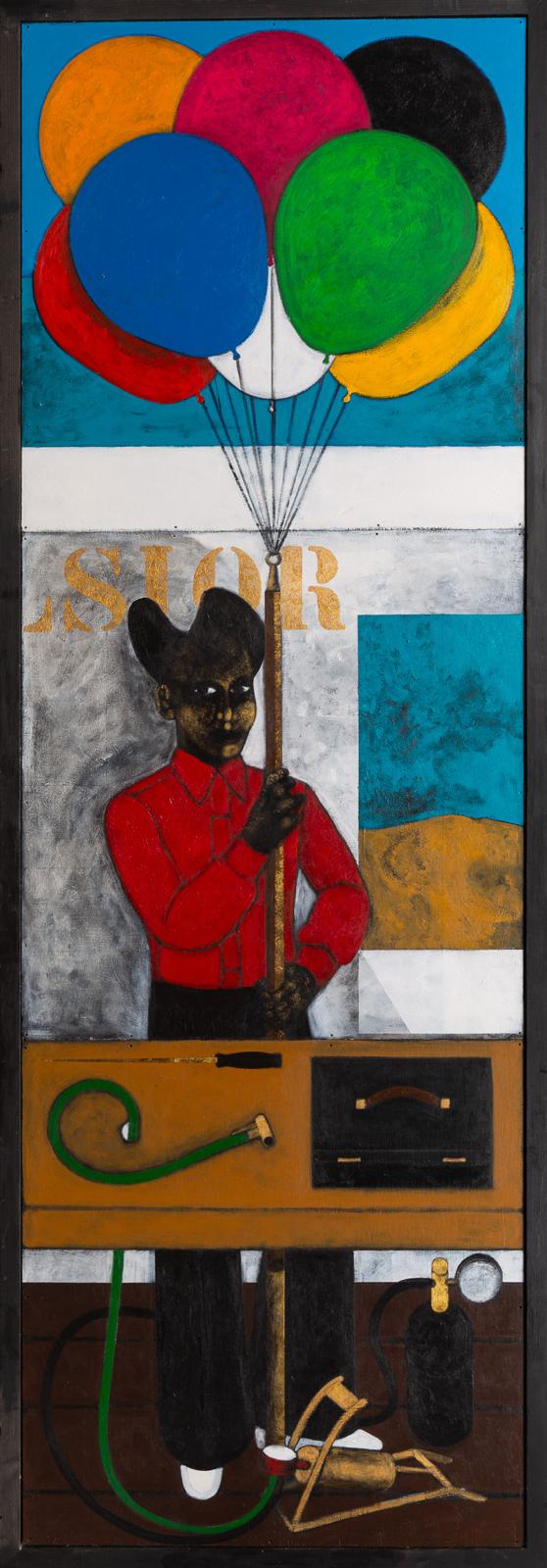

The award-winning architect-turned painter Abe Odedina wants you to experience the profound in the everyday, and use his art to truly contemplate the gift of being alive. He makes his British Art Fair debut this week at the Saatchi Gallery next week with Son of The Soil – an exclusive solo show presented by curator Virginia Damtsa in collaboration with leading London gallery The African Art Hub. Despite coming to art later in life, his mesmeric figurative work has already been shown in the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, the National Portrait Gallery (following a Portrait Award nomination for his The Adoration of Frida Kahlo portrait), Somerset House and Carnegie Hall. Odedina's work effortlessly blends deities and contemporary cultural commentary to evoke universal human stories, and provide a rich visual testament to the universality of the human experience. Drawing inspiration from Haitian Voodoo practitioners, painters of the Sacred Heart, anonymous African craftsmen, and his daily walks in Brixton, Abe’s work revives and deconstructs classic themes in order to spark dynamic narratives that bridge different eras and culture in a poetic fugue. In this exclusive interview, he tells House Collective Journal why we must celebrate the everyday and invest our spirit in all we experience.

Your work seems very much to be about celebrating the spiritual in the mundane, the ordinariness of things …

Yeah, it is that. What I'm saying as an artist is that everything is magical. It’s all about how you look at it. Every single life is worth exploring. You can see a guy walking across the road and think, oh, well, he's just coming back from work, and he does the same thing every day, and then some people might think, what's there to discover there? But everything is there. I find it very easy to imagine that all of life is going on within him potentially – it's all beautiful, tragic, heroic … it’s all going on within all of us, all at once. Whenever I'm painting in the studio, I'm not listening to music. I'm listening to Radio 4, because I like to know what's happening, and to get a sense of things to see what you can pull out from what is happening right now, what doorways it opens in thinking.

Where do the figures come from in your work, and what would you say you are seeking to transmit?

My figures are not drawn from nature. They're made up, so they're not burdened with biography, and I'm often placing my figures in very significant liminal spaces – such as a space behind a wall, or at a window. And that is because, if you think of contemplation, for example, somebody standing by a window begins to underpin that, doesn't it? Because, then it’s you in the painting – you are there by the window, and you're in that space between inside and outside. And, I just think those kind of spaces become very powerful. I like to put myself on the same side as the audience when I make paintings. I don't ever get that sense that, 'I'm an artist, and I have a privileged understanding.' No. I don't believe in that at all. I was an architect before being a painter, and drawing has always been core to what I do. I've just chosen to make this my job. I'm just a conduit. And I'm not that interested in introspection. I'd much rather look out the window than look in the mirror.

There is a very spiritual aspect to the work. Do you believe in any kind of faith or religion?

I guess I just like all of the Gods, all of them, in every religion. My understanding of them may be quite challenging to anyone who is traditionally religious, but I just think they are part of our supreme effort to understand what is going on. They're manifestations of our consciousness, across the board, and therefore, they are repositories of a huge amount of knowledge and beauty, and the beauty within religion still hits people on a daily basis. The first paintings I ever saw that really turned me on were baroque paintings made in churches and painted on wood, which is why I still paint on wood. There’s just such immediacy to those paintings for me, and there is the fact that it's art that is just steeped this sense of being very much a part of life, and an aspect of the everyday.

What would you say is ultimately the purpose of the artist?

You need to create a dialogue. You need to create something that's open. Everything in art comes in degrees of abstraction – even if you look at so-called realistic art closely, it's still a degree of abstraction. Between the interpretation of the viewer and my intention is the fertile ground where the work actually exists, because I then don't need to be there for the work to reveal itself. You will bring some hinterland; bring your own experiences to the painting. The more you as viewer bring something to the party, the more you get more from it. I think of paintings as tools of enchantment. That sounds a bit grand, but it's not meant to be. I see them very much as tools of enchantment; as things that spark off questions.

How does your notion of art as a tool of enchantment play into Son of The Soil?

In The Son of the Soil, there is actually an ideology at play, which is about people who are born in any area having a natural stake in it. If you extend that idea, it can get to an uncomfortable area, which is that only people that have a stake are the people who are born in an area. But what I'm interested in is to say that anybody who finds himself or herself in any part of the world where they feel that they belong because they're contributing in some way, then they too have a stake. And the protagonists in all the various paintings are exercising precisely that right to be – not by doing hysterically dynamic things at all, but by demonstrating various simple aspects of life, and how they're engaging with it.

It sounds almost like they are figures evoking a sense of belonging ...

These are various ideas of belonging, but you can belong in very ambiguous ways. For me, it’s not about saying this and that dramatically. It has to be more like poetry. There has to be space. There has to be distance in order to allow the work to be infused with other ideas. You need gaps. You need something that's open. I hope there's openness in these figures that could suggest a number of things and a range of possible meanings, which allows you to invest something of your own spirit in the work.

Son of The Soil is at The British Art Fair, Saatchi Gallery, London from September 26th-29th. Find out more about the artist here. All images form the show are courtesy of the artist.