London’s Foundling Museum has long told the story of Britain's first ever home for children at risk of abandonment. However, its current show shines a light on a previously overlooked chapter in its history and indeed that of 18th century London, presenting the forgotten lives of children admitted to the hospital from diverse backgrounds. Tiny Traces uncovers the stories of more than a dozen such children from the African and Asian diasporas admitted between 1739 and 1820 – piecing together incredible narratives that have been painstakingly researched by curator Hannah Dennett via personal items, physical artefacts and archival documents. These fragments of the lives of the ghosts of empire have been married with works of art from leading contemporary artists, forming a dialogue that enables visitors to explore the many emotions that arise from the archive, and ask questions about our collective past, present and future. Here, the fledgling curator tells Culture Collective why we must always look to the past to better understand the present, and explains why sharing the hidden stories of those whose voices are so often absent from history tells us more about the shaping of contemporary society than we can possibly imagine.

How did you become involved with The Foundling Museum?

I first became aware of the Foundling Museum and the history of the Foundling Hospital when my mum and auntie were researching our family tree. They discovered that my great-grandfather, Albert Owen, was a foundling. Albert was born in October 1875 to Jeannie Roberts, who worked at her aunt’s hotel in Betws-y-Coed, Wales. She had been having a love affair and became secretly engaged to Lowther Leigh Spencer, a student at Cambridge University. When she discovered she was pregnant she wrote to Lowther to ask to meet him as she had some important news, but her letter was returned unopened with a note added on the front that Lowther was dead. He had died of scarlet fever whilst at university, so never knew that he was to become a father. After Jeannie had her son, she cared for him for six months but was unable to continue to support them both, so applied to have him admitted into the Foundling Hospital in May 1876. Christened Albert Owen, my great-grandfather became foundling number 21624. I found the story of Alfred and his parents both heart-breaking and fascinating. Here was a human story which would have been lost in time without the existence of the Foundling Hospital archives, and it made me wonder what other stories were waiting to be discovered.

What attracted you to uncovering the stories of children from diverse backgrounds?

In recent years the Museum has been conscious of representing the diverse experiences of the children, to create a fuller understanding of the institution’s past. The Museum knew that there must have been some children of African and Asian heritage taken into the Hospital during the eighteenth century, because the British Empire was expanding in this period, in both the ‘East Indies’ and the Caribbean and America. This led to growing populations of the African and Asian diasporas in London, many of whom were of the poorer labouring classes.Therefore, it was probable that some people in these populations had sought the assistance of the Foundling Hospital. No one had systematically searched the archives to identify these children and trace their lives within, and beyond, the Foundling Hospital. Together with the University of Warwick, the Museum developed the PhD project to uncover the lives of African and Asian foundlings in the eighteenth-century, and I was fortunate enough to be chosen to undertake it. I loved the idea that, like with the story of my great-grandfather, I had the opportunity to uncover the hidden histories of these children. In doing so, I hoped telling their stories would bring a tangible humanity to their lives. I’ve always been interested in the everyday lives of people in the past; ordinary people whose experiences are often more difficult to uncover because they tended to leave very little evidence of their existence behind.

It took you three years to uncover these fragments of lives – what was your research process over that time?

When I began this project I knew that identifying children of colour in the Foundling Hospital archives would not be a straightforward process. Throughout the 18th century the governors did not require the origins of parents or the ethnicity of children to be recorded when infants were admitted into the institution. So, I knew I would need to search through a whole range of the Hospital’s records to try and find passing references and incidental comments which might indicate a child was of African or Asian heritage. I turned to the billets and the petitions as my starting points. In the early years of the Hospital, billet forms were completed for each child on their admission, which included the date, the unique identification number given to the child, their sex and the clothes they were wearing. On each form is a section ‘Marks on the Body’ under which any identifying marks on a child were noted. For example one child had a club foot and others were recorded as a twin to another child being admitted. This part of the billets provided the first clues to identifying African and Asian foundlings. There were references to the colour of infants’ skin in this section of the forms. Terms such as ‘tawny’, ‘a negro’ and ‘mulatto’ were written under ‘Marks on the Body’, suggesting that these children were not white. Though this language is not acceptable and no longer used, such terms were frequently employed during the 18th century to describe someone of African or Asian heritage. Therefore they are a strong indicator that a child being admitted into the Hospital was African or Asian.

That is fascinating. Tell us about the petitions mothers would fill in…

The petitions from mothers to have their children admitted into the Hospital provided my other starting point. These focus on the mothers and the circumstances surround their pregnancies and delivery, often including the names and addresses of referees or previous employers. Here, I discovered mothers who had recently arrived in London from India and the West Indies, and references to fathers described as ‘black’, as men ‘of colour’ and one said to be ‘a slave’. These were all indicators that the children born to the mothers were possibly African and Asian, so I turned to the admission books to discover the names and identification numbers of the babies received from these mothers. Once I had the identification number for each child, I was able to search further records in the archives to try and trace their time in the Foundling Hospital. It’s been a journey with moments of elation and sadness. As an historian, uncovering something in the archives which confirms what you imagined, or discovering another scrap of information which helps build the story of an individual, is everything one hopes for when undertaking research. However, searching through hundreds of petitions from mothers, which repeat tales of broken promises, abandonment, sexual violence, and destitution was upsetting. Coupled with these women then having to give their babies away, I can only imagine how they must have felt. Overall, it has been a privilege to uncover the stories of the children and their parents, and to be entrusted with telling them.

You are obviously very passionate about the show, is there a personal resonance for you?

As a single parent to three daughters myself, the mothers who came into contact with the Foundling Hospital have always resonated with me. I still find it staggering that the experiences of these unmarried mothers with illegitimate children echoed through the next two centuries, with very little changing in society’s treatment of and attitudes towards such women and their children. When we look at the lives of the women featured in the exhibition; that some arrived from around the British Empire, did not speak English, had no rights to parish relief and no support networks, these circumstances must have compounded the fear and trauma of giving birth to a child and having no means with which to sustain themselves.

What do you hope a visitor will take away from visiting Tiny Traces?

I hope visitors take away a greater awareness of the presence of peoples of the African and Asian diasporas in Britain’s past. There is a long and fascinating history of people of African and Asian heritage living in Britain, and whilst historians, archivists and researchers are increasingly telling their stories, there is still a lot of work to be done to ensure the experiences of these individuals and populations become embedded in our historical consciousness. Tiny Traces plays a small part in doing this, as part of the Foundling Hospital’s history, and of the wider history of African and Asian people in eighteenth-century London. Also, highlighting some of the Hospital Governors’ connections to the colonial world hopefully helps visitors gain a sense of the complexities of empire in this period, and it’s presence throughout everyday life.

How did you select the contemporary artists in the show?

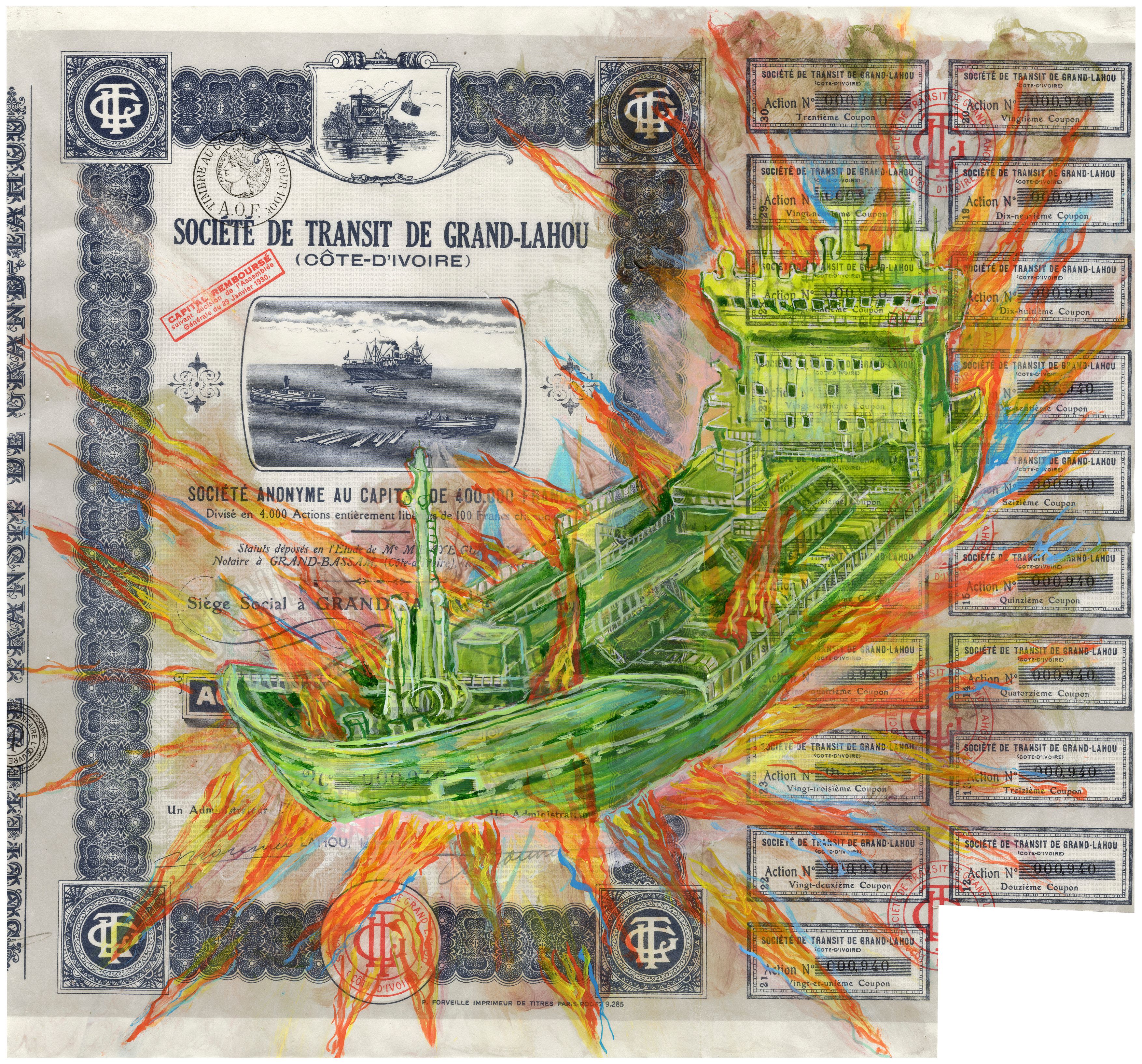

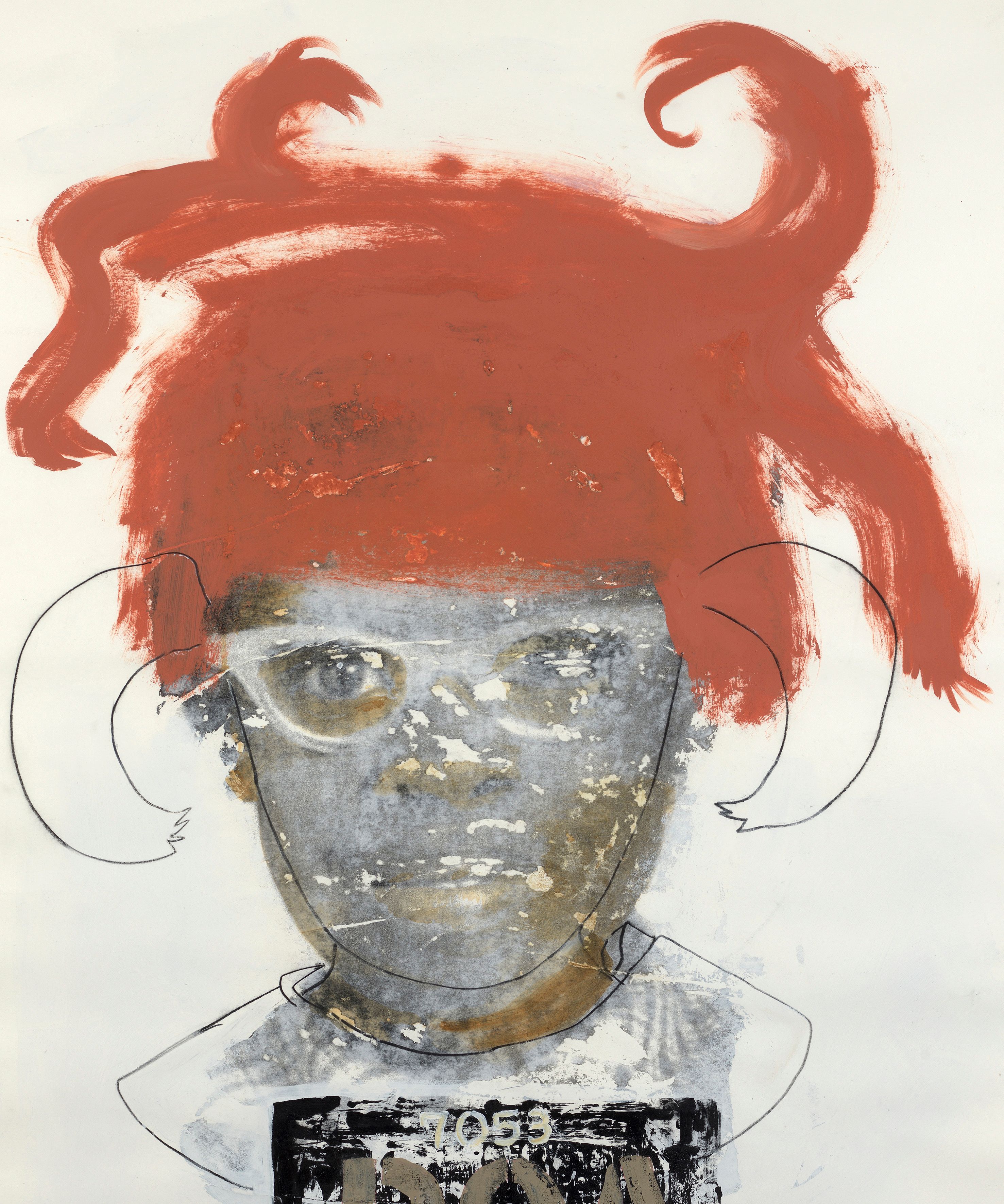

One of the challenges when putting together the exhibition was that most of the material is in the form of documents, rather than physical objects. Another was that we have no physical representations of the children, so their faces will never be known to us. I wanted to find a creative way to give the stories a more physical presence in the show, whilst also connecting them with the present. We approached contemporary artists whose work addresses the themes of colonialism, empire and identity, which run throughout the exhibition. Each artist was given the biographies of the children and we asked them to suggest a piece they thought would best speak to the stories in the exhibition. I think the pieces the artists have contributed are absolutely stunning and add another dynamic not only to the physical space, but also to telling of the stories. The results are powerful, thought-provoking art works which offer points of connection to human realities and emotions. They also bring the past and the present into conversation, raising questions about our historical story.

Does Tiny Traces have a political message that is still relevant today?

Understanding the past helps us understand the present. People of the African and Asian diasporas have lived and worked in Britain for centuries, and have therefore been part of shaping today’s society. Likewise, the British Empire of the 18th century and its role in the slave trade is still impacting the present, through the wealth this generated which created the personal fortunes of families, or which was invested in many institutions still operating. As with the Governors and the apparent disconnect they had between their colonial activities and the support they gave to African and Asian children, we too can have the same disconnect between, say, the clothes we buy and the people who made them, which often also includes the labour of people enslaved today. There will always be hidden stories of people whose voices have been silenced or are absent from the historical narrative, and they deserve to be told.

Tiny Traces is at The Foundling Museum until February 23, 2023

Images (top to bottom): Hew Locke, Société de Transit de Grand-Lahou 1, 2014 © Hew Locke. All rights reserved, DACSArtimage 2022; Deborah Roberts, 'Little Debbie (Bleached)', 2012 © Deborah Roberts. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London; Foundling Hospital token; Zarina Bhimji, Untitled (A Sketch), 1999-2010 © Zarina Bhimji. All Rights Reserved, DACSArtimage 2022; William Hogarth, 'Harlot's Progress plate 2', The Garrick Club.

All images courtesy of The Foundling Museum