James Vaulkhard is a classically trained artist who defies easy categorisation, and his latest series continues to platform not only his prodigious talent as a painter, but also his penchant for conceptual eclecticism. Inspired in part by a mythological notion of renewal drawn from Egyptology and the Japanese concept of ‘ma’, or negative space, his new series of deconstructed landscapes entitled The World Waxed Green – showcasing at Asia House this month – present the familiarity of traditional depictions of nature before dissolving into an ecstatic celebration of abstracted form, drawing the viewer into a space that the artist says is intended to inspire healing. Here, the often reticent British artist, who is selling a run of limited-edition prints from the series exclusively via Collective Culture (watch this space), waxes lyrical about his childhood in Kenya, peering into the emptiness, and the enduring power of art to heal.

When did you first fall in love with painting?

I grew up in Kenya and first remember painting wildlife and landscape in watercolour when I was around seven years old. The images that fascinated me as a child were those that focused on the silhouette – those ubiquitous paintings of African skies with that twilight zone feel of epic sunsets, and just a silhouetted figure against them. That's an image that still resonates with me from childhood. It was probably a few years later, on a family holiday to Italy, whilst being dragged around renaissance churches filled with religious iconography, that something much deeper was instilled in me – perhaps a sense that an artwork must feel like an artefact, something more than just a decorative drawing or painting. In a way, these new paintings in The World Waxed Green series hearken back to that fascination with the unseen silhouette, although not just the kind of cut-out black silhouette, rather they are about kind of looking through a landscape and discovering what actually lies in the negative space; pulling focus on that moment when you are glancing at a bigger picture but are drawn to smaller detail.

What inspired The World Waxed Green?

The paintings are influenced by the Japanese concept of ‘ma’, in that you're kind of looking through the landscape at a perceived emptiness, and peering within. If you look at a lot of Japanese art, then much of it is about the negative space – ‘ma’ is really that notion that the sort of silence between the words or the gap between the notes, actually make the cadence or music. These paintings are designed with that in mind, and they are almost sort of negatives – they’re not really focusing on the foreground, because the idea is that you are kind of looking deeper and finding all these abstract shapes in a deconstructed landscape. I wanted to explore different concepts, and ‘ma’ is such an interesting way of approaching painting. There is also a sense of coming out of the darkness in this series, which I suppose comes down to grief. My last series of paintings Weird Scenes Inside The Goldmine was painted after my father’s death, and they were very dark, because I was probably in a period of life where I was quite depressed, and in a bit of a cave. The World Waxed Green is about coming out of that… For the viewer, I hope they will see these paintings as beautiful, optimistic and uplifting works of art.

Where did the title come from and what does it mean to you?

It was a little bit of an afterthought, to be honest, because I hadn't actually come up with a title for the show. I have a tattered book of symbols in my studio that I love, and I came across a page focused upon the Egyptian God Osiris, and how he symbolises growth, healing and metamorphosis. Underneath this image, it said that ‘the world waxed green’ through him. I just absolutely loved that. Mythology always resonates with me because it transcends modern religion and culture. Also, the world has been going through the paroxysms of lockdowns and the global pandemic, and I want to be hopeful that we are now, potentially, going into a period of healing and growth again. In a sense, the paintings are a completely natural product of my feelings – I was not consciously trying to create something synthetic or follow a narrative, but ‘the world waxed green’ resonated.

What are the pluses and minuses of being a classically trained painter?

I think a classical training is like learning the chords in music, because once you know the chords, you can almost do anything. And I still think that's so important in art, although it might be quite an old school opinion. I do believe that drawing from life is such a fundamental part of art, and I think it’s something that's missing in contemporary art school – spending hours just training your eye to see composition is so fundamental. Having said that, I can find working from life quite limiting these days, because you often get to a stage where you can't really push it much further, so these paintings are almost improvised from memory. Ironically, deconstructing what we see becomes so much easier and clearer when you have your baseline in drawing or painting from life. In the story of art, those artists who make this step are always leaping into the unknown. Perhaps the award should be given to the cave painters for unleashing the human conscious. After that does history simply repeat itself?

The World Waxed Green is at Asia House, London, March 22-27th.

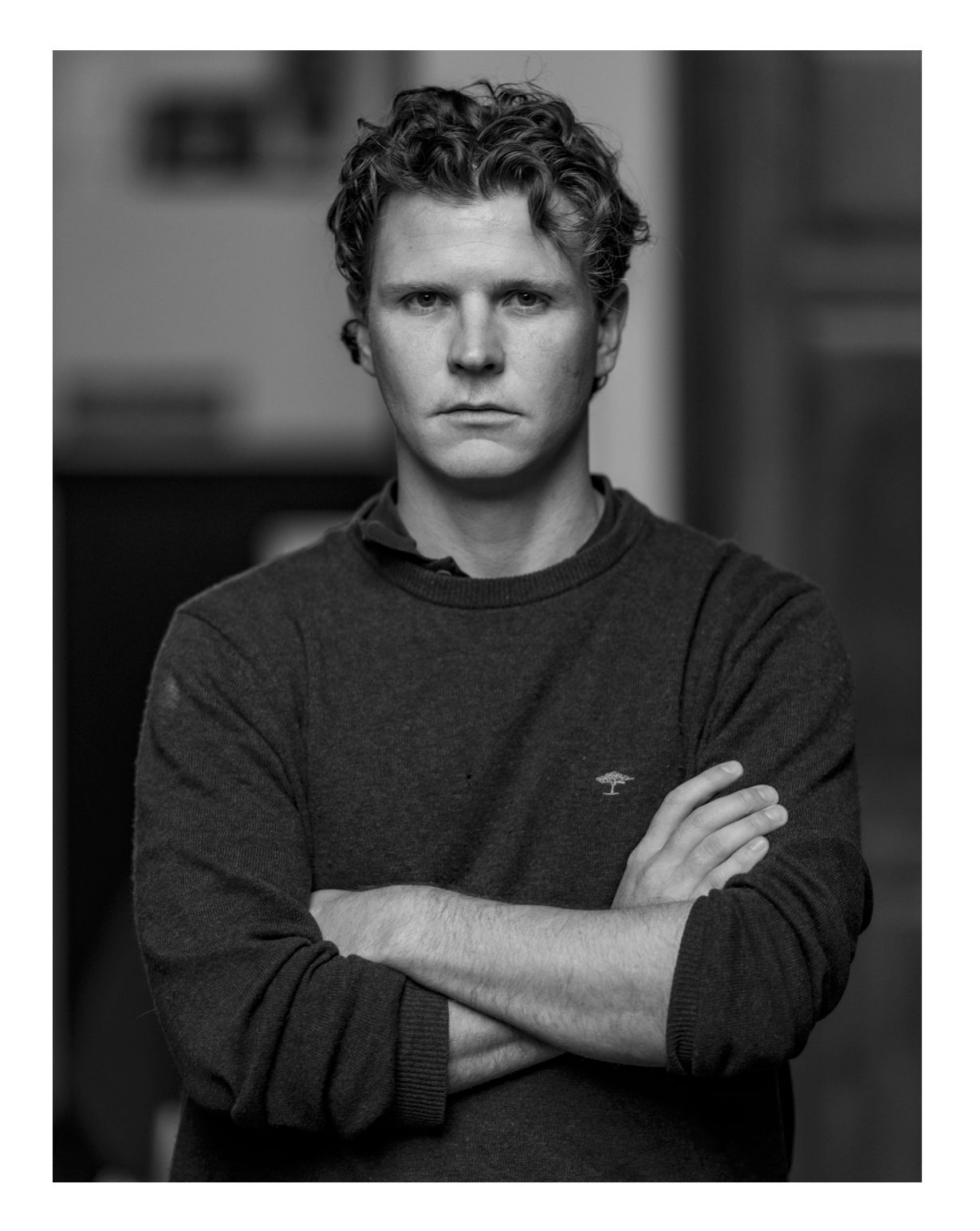

Portrait of the artist by Misan Harriman.

To purchase a limited-edition A2 print of any of the featured works contact culture@housecollective.com