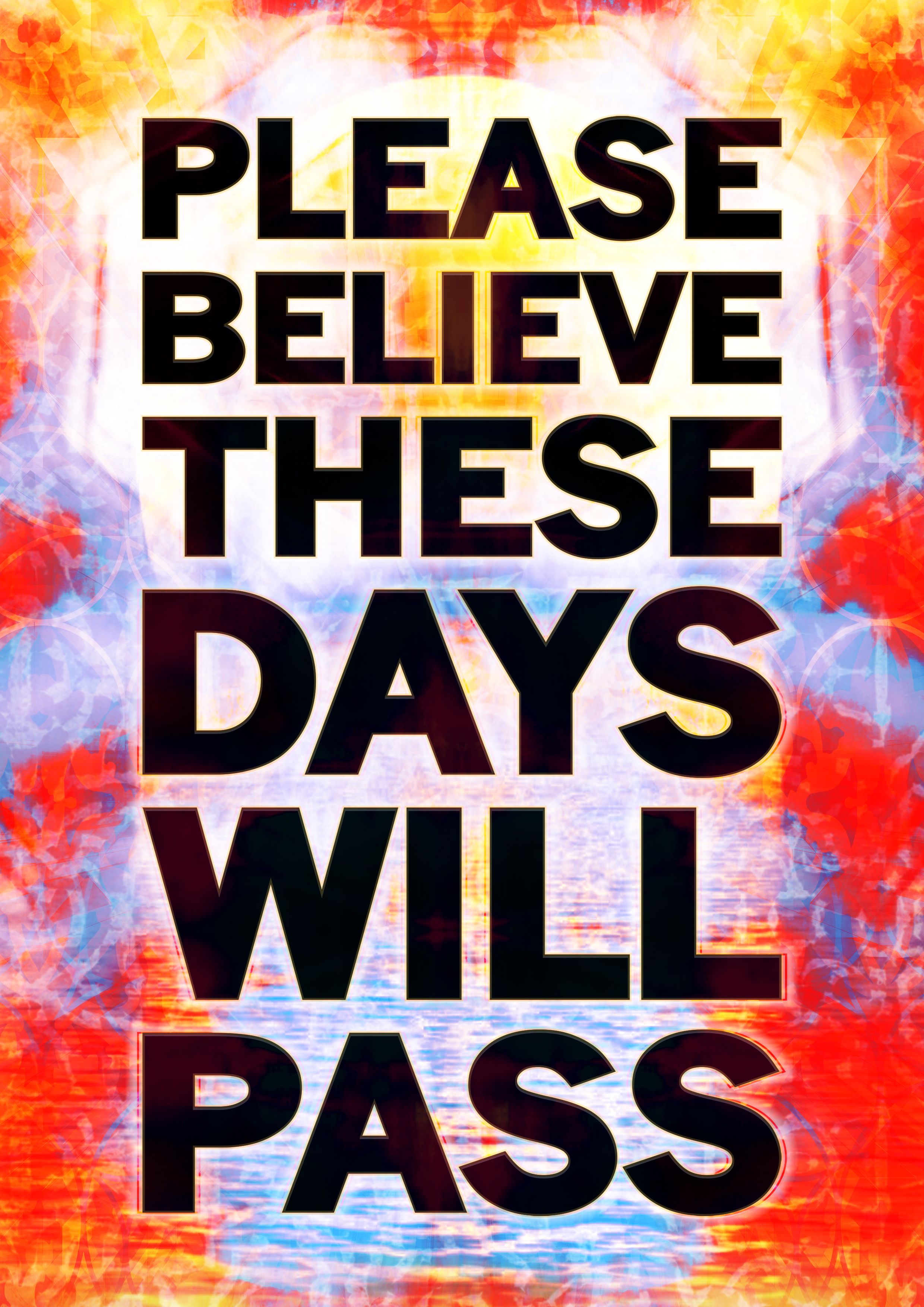

Iconic is an almost absurdly overused adjective in modern media communication. However, if an essential element of truly great art is its emotional impact and synchronous ability to pull the viewer into a present moment of radical contemplation, then there are few artists who can hold a candle to Mark Titchner. The British artist has been presenting ambiguous existential aphorisms for the populace to ponder upon for some two decades in a bold, and somehow Orwellian, typographic style that can, quite genuinely, be described as iconic. And believe us when we say, you know his work. Over the years, his thought-provoking reflections on the nature of being have graced public spaces that bear witness to a footfall of millions – elevating the London Underground commute into countless inner journeys of contemplation, with statements such as We Want Answers To The Questions of Tomorrow, and carrying us through the bleak days of the pandemic by transforming empty advertising spaces into the beautiful Please Believe These Days Will Pass. He is currently one of the artists in the group show Finding Family at The Foundling Museum, and his short looping film of statements and questions, such as Do You love Me? I Love You brilliantly explores the ways in which anything expressed can have a different meaning depending on the circumstances in which it is transmitted and received. In this interview with Culture Collective, he tells us what its like to communicate so directly with hordes of strangers, and explains why the aphorisms of the self-improvement industry might just be designed to make us feel worse, rather than better.

What would you say drives you to create these quite emotive statements in the public realm, and where did the desire to do that originally stem from?

I think it’s shifted over time. I was always very interested in lots of different things, and when I was young, and studying art, I didn't really know how to join them together – I mean, I was interested in science, philosophy, alternative technologies, counter culture … I was sort of scrabbling around when I left college, trying to find a way to work with this material and marry it with my interest in optical art, and playing with what is transmitted and received. I was looking at Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger – you know, the kind of artists you would probably imagine – but, fundamentally, I was always very interested in reading. There was this real wood for the trees moment for me, where I was just, like, oh, I need to focus the viewers back on themselves with my work, and I just thought, well, what happens if you write something? That’s when it became kind of interesting, because when you read, you sort of stop for a moment, and you really internalise something that is very specific to how you may be feeling at the time, and, of course, the writing can be about anything – so, I realised it could incorporate everything I was interested in.

Which pieces have had the most emotional impact for you – and which ones have people most responded to, in the sense that they have had a profound impact on their lives?

That’s a really interesting question, because a lot of the time you don't really know how something will be received. In 2006, I made a poster project on the London Underground. There was this poster all over London, and it said ‘If You Don't Like Your Life, You Can Change It’. And, even now, I still get requests for those posters. And normally people request them because something happened to them as a result of seeing the poster, or it reflected their state of mind, or somehow became part of their story– and that's really amazing, in a way, because that’s gone on now for a decade; people getting in touch and asking for those posters. And, honestly, I think what I'm always looking for is a genuine emotional response, rather than a sort of psychological or intellectual response. Because when I am seeing those kinds of things in advertising, I'm really thinking about, how is that intended to make me feel, and what is the undertow, or unseen element, of what is being said.

It’s interesting that you are playing with the manipulative nature of language, and yet your work is often received as a positive statement or aphorism. What were you trying to explore with the piece that appeared all over London during the pandemic?

That piece during the pandemic was amazing, you know? It was an amazing experience to see how that did chime with people. But you are right, because, again, I always thought the most interesting thing with that text was that the two first words were ‘please’ and ‘believe’ – because the idea of asking someone to ‘believe’ is to me sort of anachronistic. So, rather than being comforting, I saw the work as being something which was, like, well, you can't choose to believe in something – you either believe it, or you don't. It was sort of messing around with this idea as to whether it's possible to bring yourself to believe in something, or whether belief is something that is much more intrinsic and fundamental. But that project is also a great example of how something can have a life that goes far beyond your intention, because when you put stuff out into the public realm, in a way, it becomes about the death of the author – it takes on its own personality, and has its own personal meaning for everyone.

There’s often a very deliberate ambiguity at work then?

Yes. I guess I like to think about what's implied, and that’s often outside of what's being said directly – because, for me, what's most important is what is not being said. It’s interesting, because I think quite often my work does get taken as this very positive thing, but, for me, the ambiguity I place in the work is the critical element. Actually, I quite often see something as being demonstrative, or kind of almost Orwellian, and I think it's so interesting that our first take when we read things is to tend to look for something that must be meant as positive. And that is probably even more true now, because we are so used to this quite mechanised language of self-improvement, which, when you think about it, is actually almost kind of bullying in nature – it’s basically saying, you are not good enough, you must be better. There is a sort of emptiness to that, which I like to explore in my work – because a self-improvement aphorism is not going to change your life.

Tell me about the work you have created for the current show at The Foundling Museum …

They tasked me to explore family. And, from my point of view, I was like, well, okay, family – that's super complex, and it's entirely different for everyone. So, part of the context of the exhibition is really asking questions about what is family? Who are your family? What are family relationships? And, obviously, it is something that is extremely mutable, so I started thinking about how I could express that sense of mutability and flux. In the last few years, I've got really interested in creating a kind of dialogue in my work. I mean, I guess most of my work is seen as statement. But I've got more interested in how they can morph into dialogues, and in the work at The Foundling Museum, I was trying very much to think about how the work could almost be like a kind of conversation.

How did you set about trying to achieve a feeling of dialogue as opposed to statement?

I was quite sort of mechanistic about it, to be honest. There were certain elements I wanted to have, where I was using words, or questions, as a kind of call-and-response. And I was thinking about these ideas of what do we expect from family? Do we expect love, or belief or support – so, I kind of almost quite mechanically went through this set of things, such as ‘Do You Love Me? I Love You.’ And there’s a whole series of these call-and-response questions in a film that is about 14-minutes long. What I wanted to explore is how everything moves all the time in relationships – all these kinds of questions, or statements, take on new meanings at different stages of the relationship. I was trying to think about the kind of things that you might say when you are in love with someone at the beginning of a relationship, and how the same thing could mean something different at the end of a relationship, when someone's let you down, or the opposite, and the film continuously loops, so the journey becomes sort of endless, with the meaning constantly changing.

Finding Family exhibits at The Foundling Museum until August.

You can find out more here. All images courtesy of the artist.