The Brooklyn-born art dealer, gallerist and author Joe La Placa He has played a role in the lives of some of the most celebrated creatives of the modern era–facilitating the likes of the iconic Jean-Michel Basquiat to produce his first ever show at New York’s Annina Nosei Gallery, and he has elevated the careers of many notable contemporary artists. He is currently director of The Cardi Gallery, Mayfair, where he provides a unique perspective on the heroes of Post-War Italian art. Here, he tells Collective Culture how his grandfather’s love of painting kick-started his career, and explains why an up-close-and-personal experience of art is more important than ever in the digital age.

How did your creative journey begin?

My journey into the art world began with my grandfather. He was a kind of rags-to-riches immigrant story–a cobbler from Sicily who started out in America sweeping the floor. Towards the end of his life, he was a partner in a company that manufactured shoes for all the big department stores in The States. He built an incredible house around the corner from where I used to live in Long Island, and it was there that I used to watch him paint on Sundays. I remember the day he said to me that he would buy me some oil paints of my own. I couldn't even sleep the next week, I was so excited, but on the morning that I was supposed to see him, my father told me he had died. I still remember walking into that house on that day–all the Sicilian ladies dressed in black and crying, and my grandmother saying to me: now the paints are yours, he would have wanted you to paint. I stayed at my grandmother's that night to keep her company, and painted a still life that I still have today.

How did a passion for oil painting evolve into a pivotal role in the 80s New York art scene?

I suppose I just knew what I wanted to do before most people–I knew art was going to be my trajectory. I had this amazing art teacher who took me under his wing, so my formal training began very young–looking back, I was always lucky to have amazing mentors. I wound up getting the same scholarship to SVA, New York, as Keith Haring, and that's when I became involved in the downtown scene. I was just surrounded by inspiring figures–Donald Kuspit, the world's greatest living critic, Julian Schnabel, Kenny Scharf… I started pretty much living in galleries. I worked for Leo Castelli. I worked for Sperone Westwater Fischer .By 1984, I had my own production gallery Galozzi-La Placa focused on street art, and Jean-Michel Basquiat was using the basement as a studio. I used to close my gallery for three months at a time and invite graffiti artists to come over, giving them materials like polymer to work on. I was someone who was steeped in art history, but I had this real passion for working with living artists.

Why do you think you became set on facilitating the work of other artists, rather than focusing solely on your own?

I think a spirit of generosity is in there somewhere. I mean, I had a lot of knowledge from a young age, and I wanted to share that knowledge with people. I always had this sense that art was vital and far more than an asset class. I think that crystallised for me later in the book I wrote with Phillip Romero: Phantom Stress. It documented his life’s work and how traumatic memories from the past become non-conscious, and get triggered in certain situations years later in life. Initially, I was just going to help him to do the book proposal, because he had got a big deal from Random House, but I ended up travelling all over the world talking to neuroscientists about the effect of art, and it had a profound impact on me. We came up with the idea that art was imperative for human survival because it helps us become more adaptively resilient to chronic stress.

Is that notion of art as a healing experience still core to what drives you?

That healing experience of art is possibly needed now more than ever, because in the last ten years, or so, we’ve become so used to everything being mediated by the screen, and the addictive source of light that comes from our smart phones. Modern psychiatry has actually coined the term screen syndrome because of our habitual use of screens for six/seven hours a day, andwhen we don't have a screen to look at now, we can begin to feel anxiety and withdrawal. I have to say that when I returned to The Cardi Gallery after the recent lockdown, the vividness of the paintings was just so strong–it was such medicine after looking at things on the screen for months. The experience of seeing an artwork in the virtual sphere is never going to get close to the richness of the physical experience, and creating that sense of physiological elevation is, for me, a big part of the artist’s role.

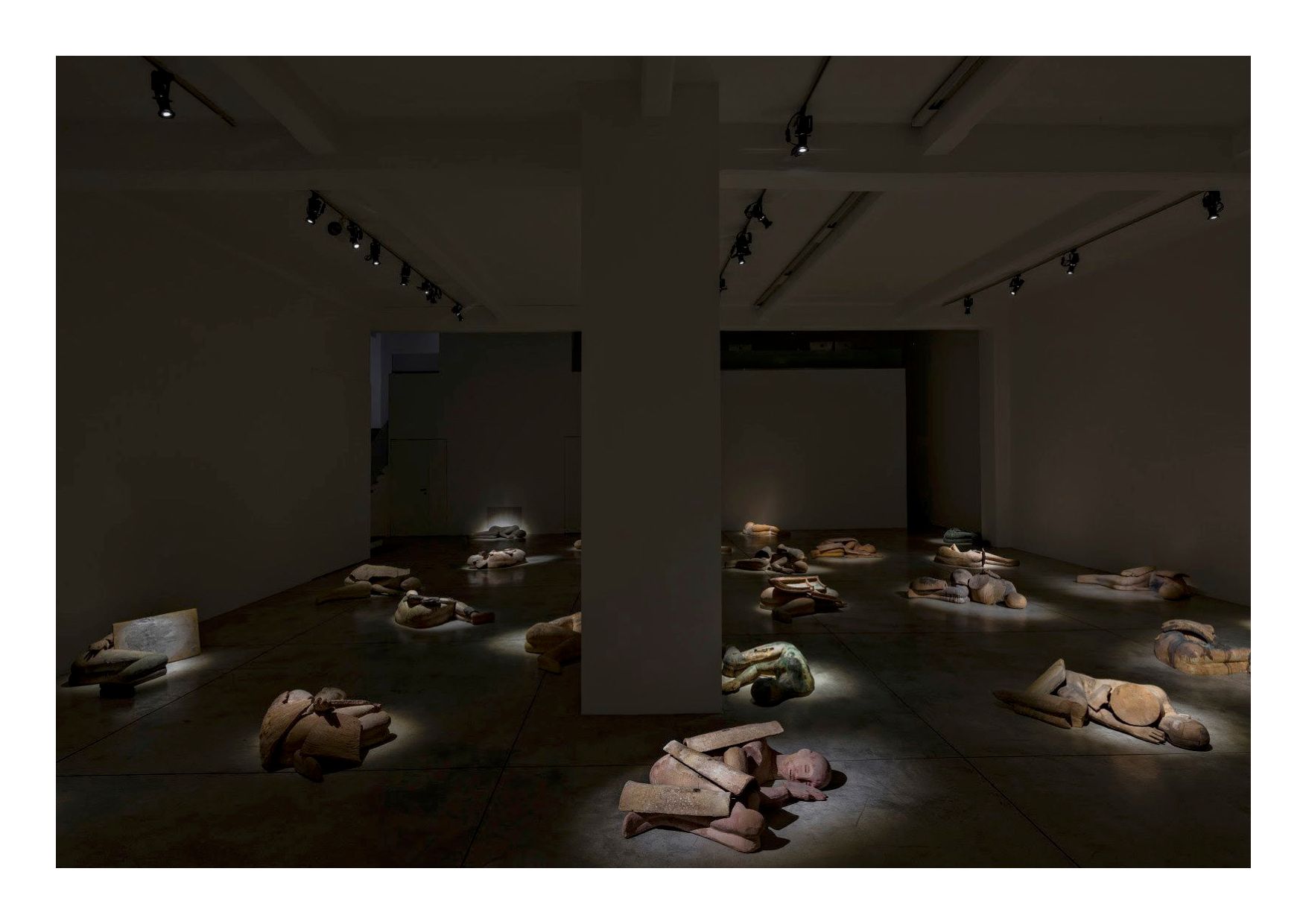

Credits (Top To Bottom): Mimo Paladino Installation 2021, Image by Carlo Vannini.; Lee Ufan's Relatum 1969-1995 Iron (5 parts); Lee Ufan's Relatum, 1969/1995-2015 Stone, cotton-wool, iron. All Images courtesy of The Cardi Gallery, Mayfair.