The London-based painter Barbara Hoogweegen embodies a profound exploration of human experience in her work via an idiosyncratic blend of both abstract figurative and classical landscape. Her award-winning paintings, crafted meticulously on various surfaces, including canvas, board, book covers, and aluminium, evoke a haunting nostalgia that resonates deeply with the subconscious mind. In her creative process, Hoogweegen delves into the psyche, identity, and themes of solitude, revealing layers of emotion that inspire reverie, inviting a dialogue with the viewer that underscores the subtleties of self-reflection. For Hoogweegen, the pleasure of painting lies in the journey of discovery – every single stroke revealing a new facet of the narrative, each layer unearthing unseen connections. As such, the act of painting becomes an intimate exploration of the self and the world, and a conversation that continues beyond the canvas, encouraging the viewer to explore their own internal landscape. In this interview for House Collective Journal, she tells us that, for her, the joy always lies in the process, and explains why a painter should always seek to pack an emotional punch.

What would you say most inspires you as a painter?

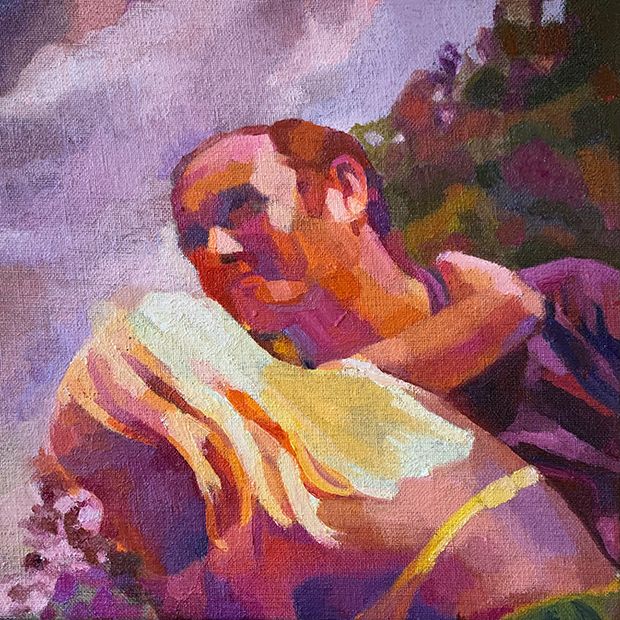

As an abstract figurative and landscape oil painter, I am inspired to communicate themes around the human psyche using the figure and the landscape. The message is often sensual – how it feels to surrender to nature, enjoy a tranquil swim at sunset, lose yourself in a book on The Underground, or experience the glorious feeling of sunshine on your face.

How does your Dutch heritage play out in your work?

I left Amsterdam as a child, so aside from enjoying my Dutch, surname, which, on some level, attaches my work to the history of Dutch art, I don’t feel it plays much of a role. My time in Trinidad, however, was very influential. My mother was very close to painter, dancer and musician Boscoe Holder, who was my first major influence. (He and his brother Geoffrey were recently given a retrospective at Victoria Miro gallery). I used to spend hours watching Holder paint. He took his work everywhere with him, and often set up a table on the beach we went to most weekends. When people ask me about my colour palette I explain it originated from a combination of Holder’s palette and the vibrant Trinidadian scenery.

Why do you work chiefly from found imagery?

I sometimes work from life, but mainly I paint from my own photographs, film stills and found images, thereby engaging with the slippage between the felt and the photographic. Regarding portraiture, I use the face not so much to portray a particular person or their likeness but as a vehicle to convey a narrative, a sensation, or an impression. I am drawn to using the face in my work, as it is such an effective tool to convey an infinite variety of worlds, through emotion, gesture and posture. The face also provides me with a resource of colours, shapes and expressions to play with and dilute. I often hope to pull out and exaggerate the particular emotion in the subject I am painting from, and to quote Alex Katz with each painting, ‘I hope to pack an emotional punch.’ After formulating an idea for the subject of my work and what I hope to communicate, I either take photographs or search for images on the internet to use as source material.

Do you think the Internet is an invaluable tool for artists?

The experience of looking for an image on the Internet most closely replicates searching for a recognisable face in the crowd. I am able to choose from a vast array of images of people in my search for the most suitable. The searching process on the Internet can be fast: my mind is rapidly computing and registering hundreds of faces/images until it rests on one that is suitable. I wait until I recognise an image that strikes me on an emotional level and for my desire to be ignited. I look for facial expression, gestures and postures that would best enable what critic Alan Roughton describes with regards to the power of the ‘detail’ in poetry. Roughton describes how: ‘It is in the concrete and vivid detail that poems live and through which they convey emotions and make their ideas vivid.’ Painter Eric Fischl describes how: ‘[...] gestures trigger memory and associations [...] I use them as doorways or entrances to events that will evoke similar feelings and associations in the viewer.’ He also describes why photography as a source material is so useful. He said, ‘There is something you get from a photograph that you can’t get any other way, awkwardness. The photo cuts time so thinly that you get gestures you don’t normally notice.... For me, the photo is a view into the soul of a character because so much of the arrested motion is unselfconscious.... What I like about the photograph is its degree of realistic depiction.’ Once I find the image containing the gesture that triggers the relevant feeling relevant to the subject matter, it becomes the source material from which I create an image of the imaginary. I aim to keep the image in potential: in other words, to distil the descriptive and create a bare minimal structure for the viewer to dress with their own similar experience.

What is the intention that drives you?

An intention that applies to all my work is to deliver an emotional and retinal punch to the viewer. As Katz described: “I wanted to make a painting you could hang up in Times Square. I wanted it to have muscle and aggression”. The photograph is therefore merely a starting point. Richter explained how a picture transforms when he paints from a photograph: “Something new creeps in, whether I want it to or not. Something that even I don’t really grasp”. What does my work mean to me? Given strict instructions from one of my first tutors to be willing to “burn everything I make”, I was lucky to appreciate that the real pleasure in painting is in the process.

Find out more about the artist here