Supersublime is a powerful and timely group exhibition curated by artist Theo Ellison that seeks to explore the ways in which Romanticism and fantastical speculative future narratives are shaping the digital age – drawing parallels with the ways in which the impulse of the movement has similarly responded to practically every seismic scientific advancement in recent history. The show argues that Romanticism continues not only to define so much of our aesthetic taste, but also provide a counter-intuitive foil to progress, postulating that the backlash against AI has much in common with the way Romanticism looked to reverse scientific logic in favour of a ‘return to nature’ during the Industrial Revolution – favouring idealism over reality. While all of the artists exhibiting investigate different strands of this paradigm, Supersublime largely stares into the anxiety abyss that the emergence of AI has delivered en-masse, playing with the strange relationships between technology, nature and nostalgia in ways that make us think about how we consider the likes of deep-fake videos and augmented reality. Here, Ellison talks to Culture Collective about some of the different responses in the show, and takes us on journey towards what he calls the digital sublime.

Supersublime is a show realised on a massive scale. How did it come together and what inspired its conceptual genesis?

The idea emerged as an offshoot from my own practice, which looks to dig into our relationship with Romanticised narratives. The idea was to explore how those narratives map onto the digital age in conversation with a bunch of artists across different generations. I felt that it would be served well by a big space, and GIANT offers that scope. Thanks to AI’s newfound grip on the public consciousness – which appeared about six months after the show was set in motion – it feels zeitgeisty, or at least I hope it does. The advance of AI is frightening on many levels, of course, but I am trying to both indulge and undercut that anxiety in this show, because it could be argued that with other big tech leaps – the Industrial Revolution, or the Internet, for example – seem to have had a net positive effect. That is despite the catastrophic dangers they both pose.. We are at such an interesting moment with AI because it feels so accessible. We are all still gathering our thoughts about it while it just plummets ahead.

Do you think we are genuinely aware of the potential dangers?

Discussions about the most pressing dangers of deep fakes, as well as other potential pitfalls, are being had everywhere, but it seems like we are all now just along for the ride. Surely there are serious unforeseen dangers, but I like indulging in the gothic horror of it all and having fun playing with these dystopian premises. Everything to do with AI is progressing so quickly… I often feel like I’m watching The Matrix or The Terminator on a loop just thinking about it. Looking back to the ways in which key figures in the Romantic movement responded to the Industrial Revolution, they saw scientific progress and even other forms of progress as undermining nature or ‘the natural’. I find myself drawn in by this mode of thought, but am also sceptical of it. That tension is explored in the show, with the artworks oscillating between those two states.

Which works in the show most successfully evoke the digital sublime?

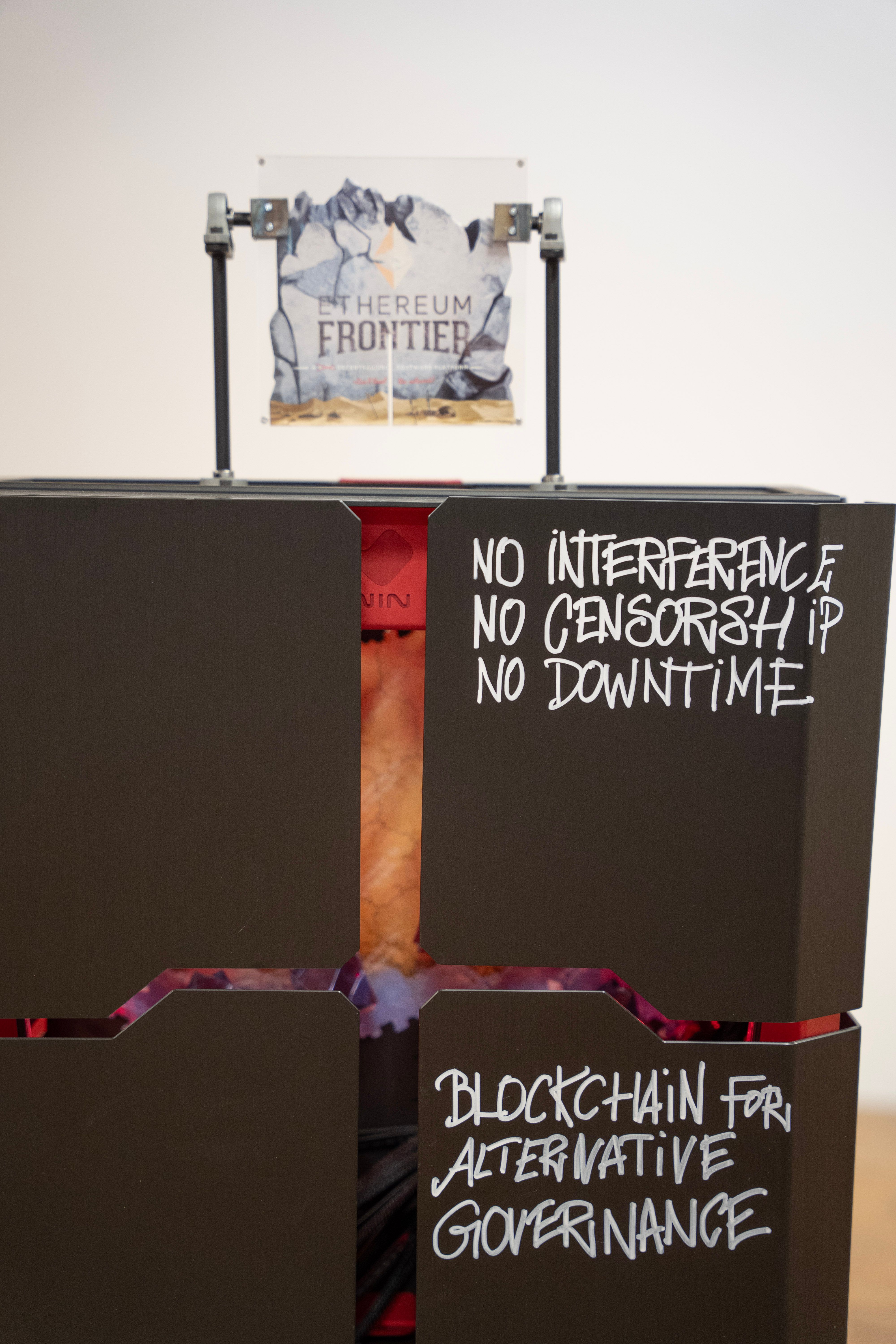

It is tricky to talk about select works in isolation, because there is a lot of overlap between the artworks included in the show. But one example is Simon Denny’s ornate Transformer-like PC case, which explores the mythologies that permeate cryptocurrency. The world of cryptocurrency is an almost perfect marriage of Romanticism and technology, because it held this ideological promise in the beginning about retaining individual agency and the decentralisation of currency. Despite the usefulness of the core technology, the honeymoon period has worn off, and what remains seems little more than gambling, speculation and get-rich-quick schemes. Crypto’s sublimity is found in its overbearing scale, both technological and economic, and that is what appears to have convinced young guys to believe that they were the next Warren Buffet in-the-making. Key figures in the space were often viewed as demigods to be followed, and as their acolytes they could grab a slice of a new frontier. The crux of what presents as a far-reaching cult is rooted in a romantic idealism that is tied to the communal upkeep of crypto, and the marketing that surrounds it – a sophisticated pyramid scheme, perhaps. Simon’s kinetic sculpture, made in 2016 before crypto’s first major crash, riffs on that failed mantra of promised economic decentralisation.

Triantafylldis seems to have a backbone of romanticism also in his huge battle scene – tell us about that piece ...

Theo has created an infinite simulation that adopts the Tolkienesque fantasy aesthetic of video games like World of Warcraft. To my eyes it also plays with the relationship between Romanticism and revolution – with paintings like Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People as a reference point. What is so great about the work is that it sets off the duality of Romanticism as a movement – a seductive entry point into a power-to-the-people revolt, but one that also feels reminiscent of the 2021 Capitol insurrection, and images of the infamous ‘QAnon Shaman’. Romanticism is full of contradictions and dualities. It appears both progressive and backwards-looking, philosophical and anti-intellectual. And in its primal immediacy, this work indulges in that chaotic combination of seduction and repulsion.

There is an apocalyptic element to it also – do all the works share a dark sense of unease in your opinion?

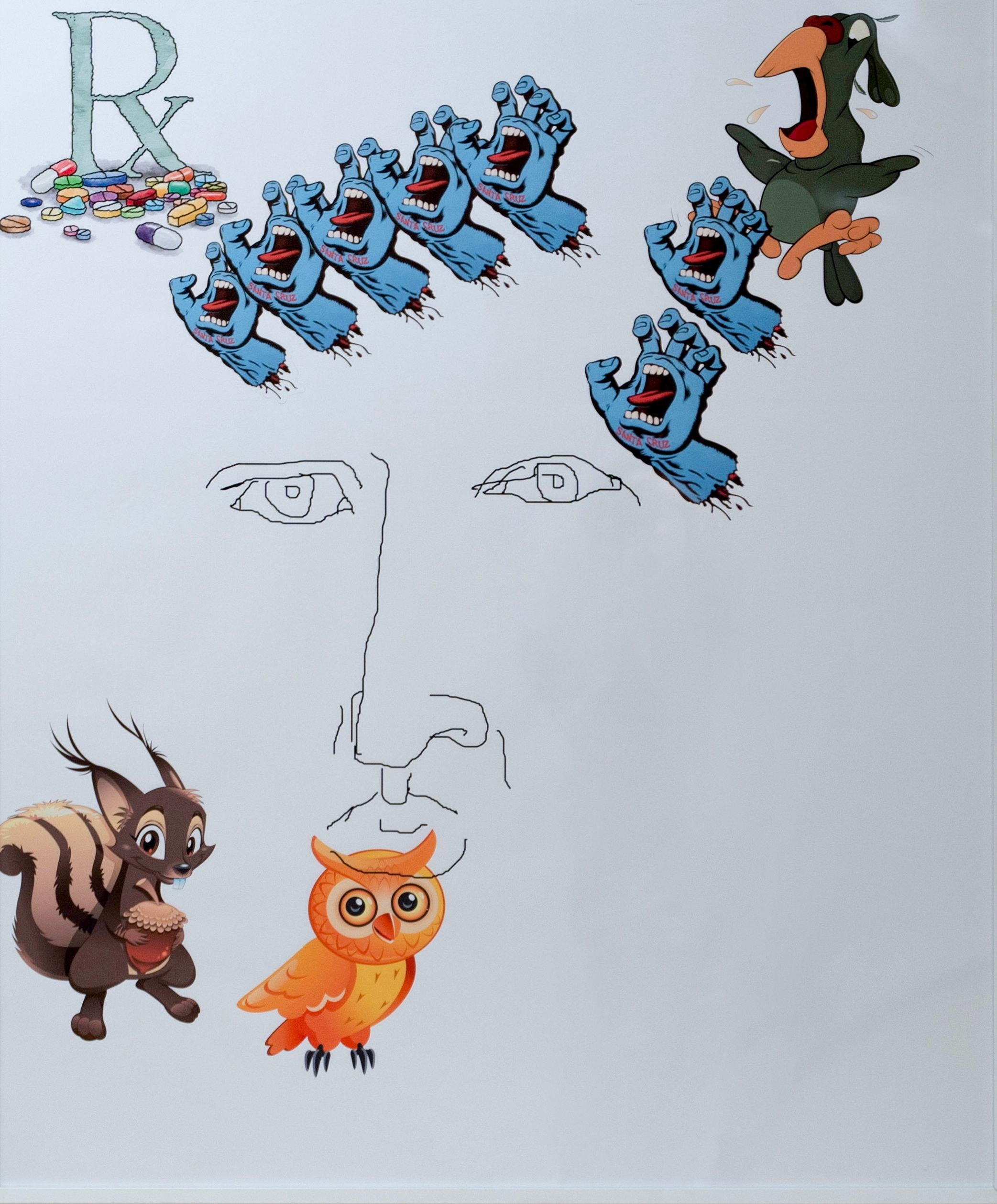

I think most of them do, at least when viewed in the current climate. The show generally aims to resist the melodrama of a John Martin landscape, gunning for a more slow-burn, uncertain take. When seen through that prism, Jordan Wolfson's prints in the exhibition engage with the formalism of different mediums, both traditional and emergent, to exploit how we construct and consume imagery in all its digitally-mediated decadence. The transition from the transgressive to the nostalgic is a process that happens over time, and his work plays with that. It is also a narrative that can be mapped onto the emergence of new technology and our acclimatisation to it. With its absurdity and dark humour, his work feels more unnerving than morbid – in that sense, it has parallels with Warhol.

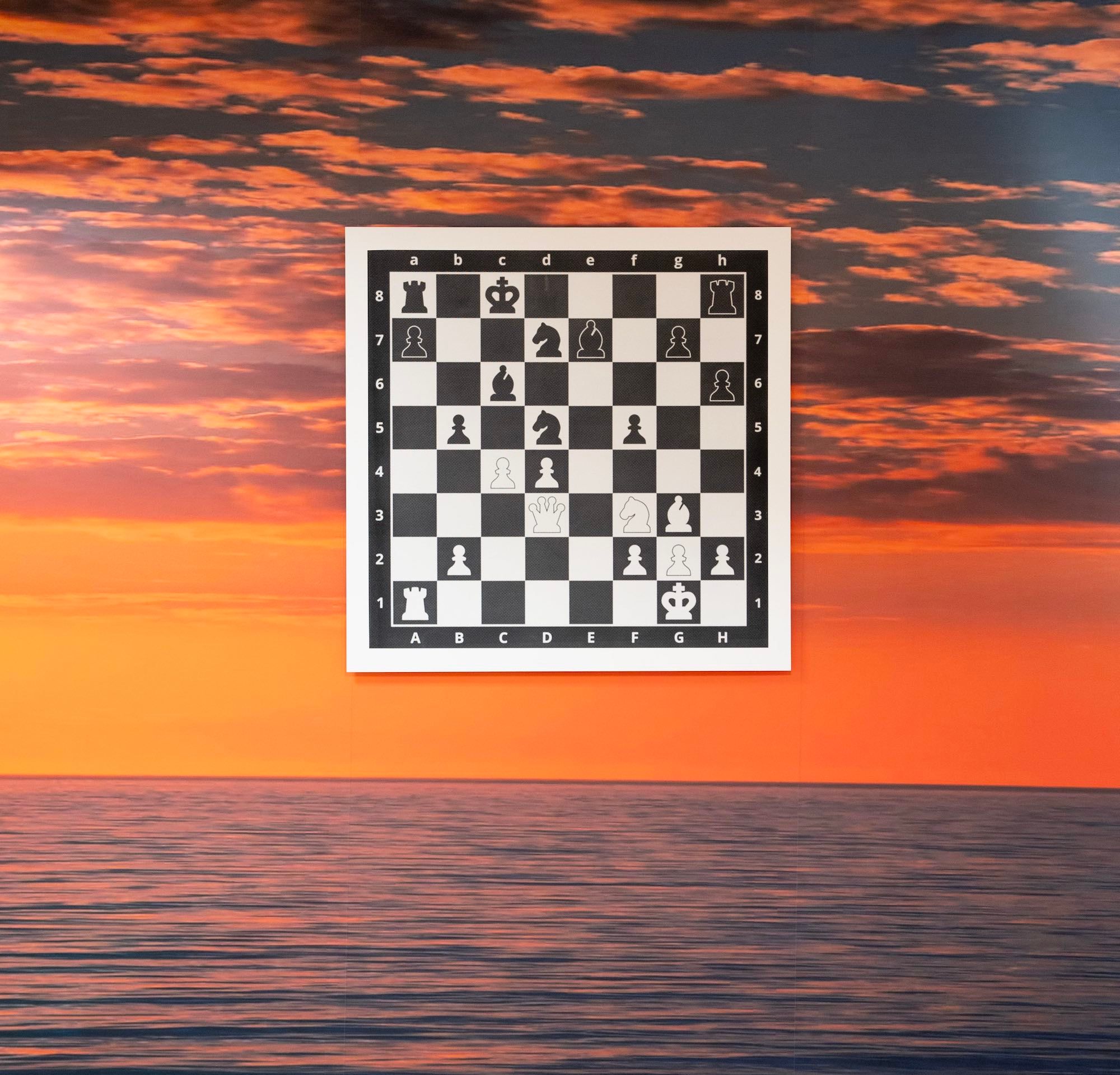

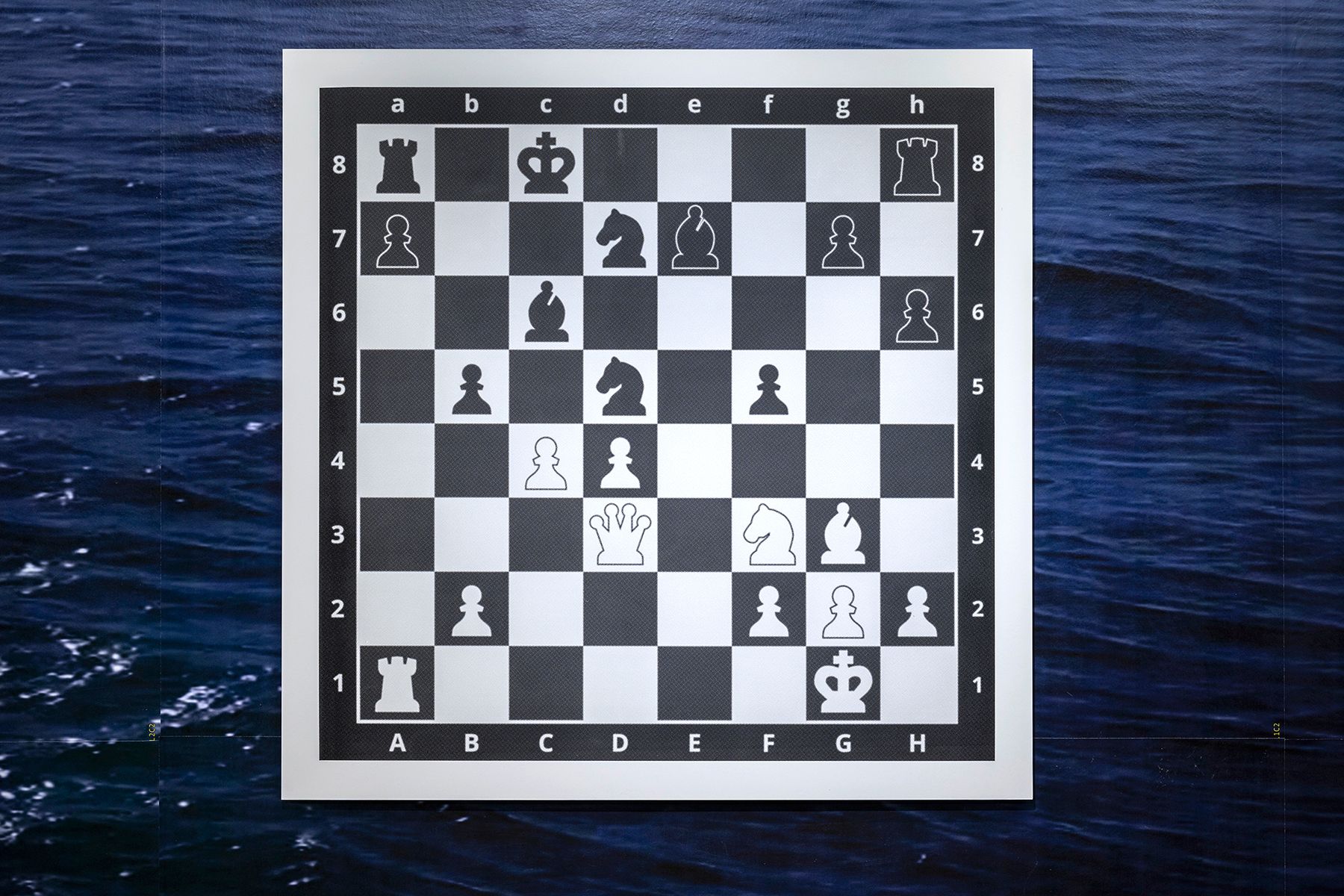

Chess plays a significant role in the show via the work by Damien Roach – what does that piece have to say to us about AI?

Damien’s installation is made up of many disparate parts, but one element is his chess diagram of the historic 1997 match between Garry Kasparov and Deep Blue. It is a stark graphic of what was a game-changing moment in the development of AI. During the second game, Kasparov became flustered as the computer began to play more ‘human-like’ moves, at one point suggesting that the IBM team had cheated by consulting a grandmaster to vet its decisions. He ended up losing the match. The work is a representation of a kind of ground zero of AI, at least in popular culture, with the chessboard serving as a real-life battleground for our existence. We are now at a point where a chess app on your phone can easily overcome any human opponent, which proves that AI has mastered that specific form of intelligence. The discourse surrounding the possibility of trying to reign in AI is ongoing, but ultimately it cannot be unlearnt and will likely just plough ahead via our own curiosity. That is how it seems anyway, before any space for hindsight. With that in mind, Damien’s chessboard acts as quite a sobering milestone. It will be interesting to see how we deal with our ever-increasing anxiety around AI over the next few years, and it should provide fertile ground for Romanticism to take centre stage.

Supersublime exhibits at GIANT gallery until September 9th.

Find out more here.