The iconoclastic Carlo Brandelli has carved a unique career in the creative sphere that effortlessly pivots between art, fashion and design. Initially blazing a trail in the early 90s at the helm of game-changing concept space and ideas incubator Squire, he has since spearheaded industry-defining menswear (his ‘unstructured suit’ was exhibited at MOMA in 2017), and has had various sculptural interventions exhibited at some of the world’s most prestigious art galleries and cultural events, such as Frieze and Pitti Uomo. Here, he tells Collective Culture how a childhood steeped in the mysteries of Catholicism spurred a passion for ideological purity in design, and tells us why his most recent artistic collaboration with Wilczynski turned out to be eerily prescient of the current global situation.

Can you pinpoint anything in your childhood that turned you on to a career in art and design?

I'm Italian, and was brought up Roman Catholic, so my earliest memories are really of being in The Church, and that made me very aware of some kind of positive or spiritual energy from a very young age. As a child, I was acutely aware of how it felt to be in that space. I would look at the shapes of The Cross, and what people were wearing, and I would be constantly thinking about the surroundings and the energy of the space, without understanding what it all actually meant–so, shapes, colours and a profound sense of ceremony have always been important to me. I have never really believed, as such, but, in a sense, I do believe that everything we see, if we have an opinion about it, is informed through some kind of spiritual ideology–and that is never conscious, it's unconscious, and just kind of instilled in the mind.

How does spirituality play out in terms of your design practice?

I think what religion, and something like the discipline of Tai Chi (which I have practiced since I was a teenager) gives you, is a route to understanding fundamental truths. The only ones that are actually important–love, compassion, understanding, and things like that, not material possessions, or what you think you should or shouldn't do because you've got a commercial deadline. Because of that, I’ve never been someone to fit into some kind of material, capitalist idea of what design means. Everything I do is positive, and I will only work with people that employ me to do things that they like about my work, so that I don't have to bend, or change what I do. With everything that I create, I'm in 100 per cent, because anything less just isn’t truthful, for me. I believe what we call spirituality is instinct, and I fundamentally believe that there is a right thing, and that that right thing is absolute, and that people instinctively know what it is–my design practice is very pure, in that sense.

Who is inspirational to you in terms of the home and interior design?

I have always liked the first minimalist interior designers, who really understood that spaces needed to change, and that a new standard needed to be set. When the minimalist movement began, it was quite shocking this notion that you should eliminate possessions in an interior to free the mind of clutter. Further back than that, people like Carlo Scarpa and Gio Ponti really thought about their work in terms of what they believed in, and political and social ideology. And all of these people were incredibly spiritual. Carlo Molina, for example, had a great belief in the afterlife, and was fascinated by Egyptology. He was making beautiful things whilst being informed by this idea of continuous living, and that nature was somehow important. If you look at his work, it’s very organic and has a deep sensuality–but importantly, it’s also very otherworldly, and will probably not look out of place in 500 years time.

Tell us about your recent art intervention Bound 1 In Liminal Possibility…

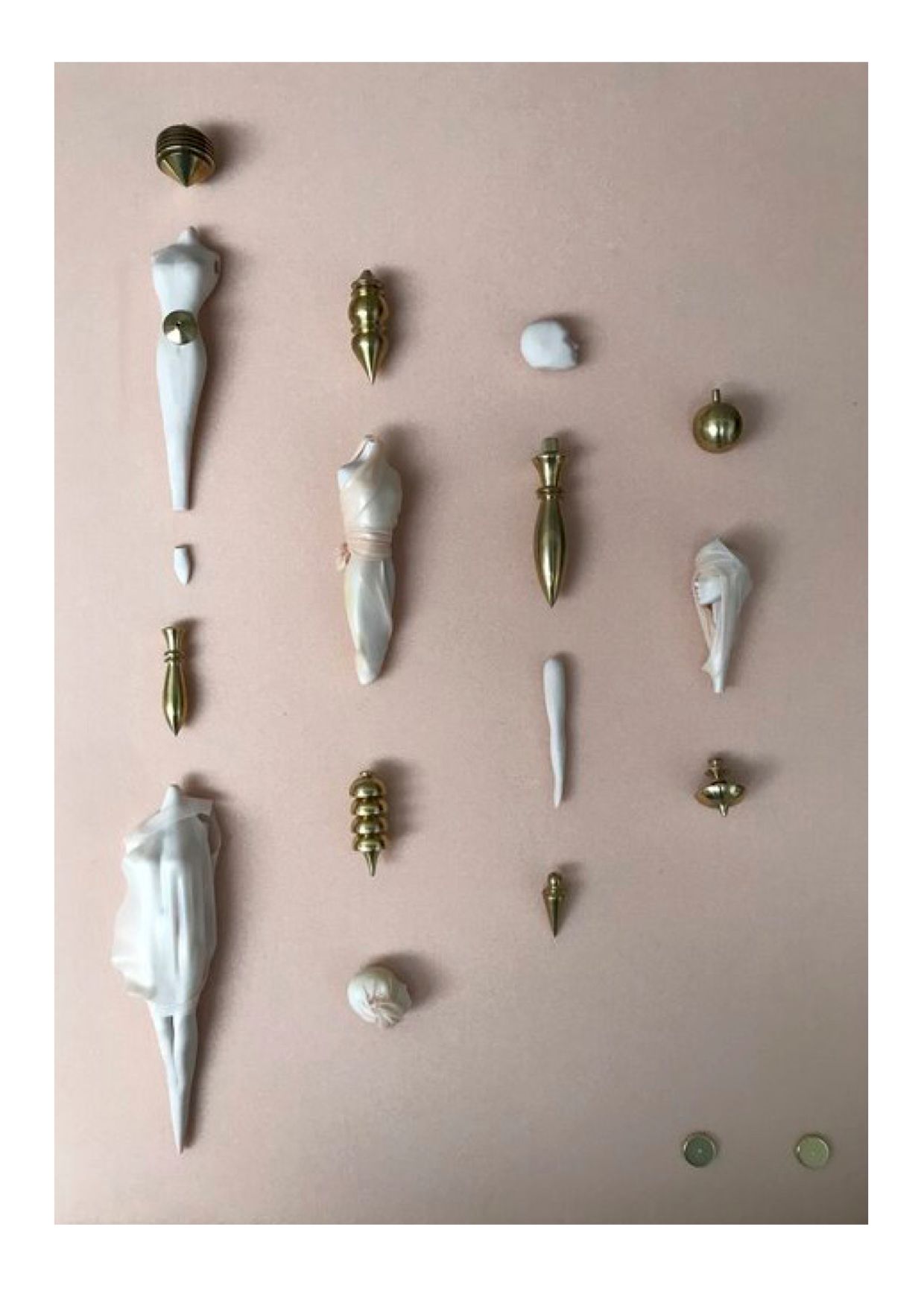

My collaboration with the artist Ewa Wilczynski is installation and performance-based and heavily involves ceremony, touch and intimacy, so the piece can't really be performed for the foreseeable future. We performed the piece in London and Paris in January, because I had this real sense of urgency at the beginning of the year that it just had to happen. Every viewer entered the space we created individually, and got to touch the sculptural pieces in their own hands, which, you know, is very, very rare in art. In some ways, it was a very isolated experience of objects and space, which was somehow prescient of how things are going to have to change, at least for the next couple of years. If you're putting objects into an environment now, then either the space needs to be very open plan, with nature flooding in, or you go the other way and create very intimate small spaces, so that in every room you are alone with the products, or whatever it is that you want people to experience, in complete isolation. In a broad sense, safety is going to be the new luxury, and designers and artists are going to have to respond to that.

Credits (Top To Bottom): Portrait by Nick Knight. All images from Liminal Possibility courtesy of the artist.