Sarah Needham is an artist and academic interested in unearthing hidden histories of humanity, taking into her conceptual sway the likes of piracy, the colonial slave trade and the witch hunts of the 17th century. She does this via a painstaking archeological extrapolation and finessing of pigments from the earth, which she then employs to create abstract Rothko-esque canvases that seem to invite the viewer into contemplation of the infinite. Her practice hinges very much upon the notion that the very material she uses to create her art carries meaning in-and-of-itself – with pigments broken down by pestle and mortar that have their roots in the political and social upheavals of history. The key postulation being that the critical deconstruction of the material history of very ordinary things, such as plates and crockery, can give us all access to a common universality of being. In fact, all of the hues present in her works tell stories of the geological history of the earth and the overlooked everyday human interactions that shape our history. Here, she discusses the nature of the sublime, the enduring legacy of Rothko and explains why she is drawn to seek to uncover universal truth.

When did you first know you wanted to pursue abstraction as a form of expression?

When I was in my sixth form, there was a really tragic accident involving friends, and it was my first real experience of bereavement. I remember going to the Tate and sitting in the Rothko room, and just feeling recognised somehow – that's the first time that that kind of profound relationship to what you are feeling and what's being expressed in a painting kind of came together for me. It’s hard to put into words, but it felt like I was held in that space by the work. It touched me in a very profound way that was that was unexpected. I think in that moment I knew what I wanted to do – that's where the decision that art was what I wanted to pursue came from, and that desire still means creating things people can get a little lost in, and find the corresponding thing within that's sitting in themselves. I want people to be able to fall into my work. I suppose I'm looking to touch the universal things, and that's a really hard, difficult thing to do.

In a sense then you are seeking to activate presence and reflection?

It's kind of reflection, but it's kind of connection as well. I’m interested in understanding how people are connected to each other across the globe, and ideas about universality – what are the essential things about being? What do you get to when you strip away the cultural elements that we have? What are those essential things that are common to everybody? In the research that sits behind my work, there's a literal way of looking at that, and then in the actual abstraction that I get to, there is a more metaphoric and poetic way of looking at that.

Is it important for the viewer to be aware of the research?

I think the purpose of the journey of the viewer with any kind of art is to find something out about themselves, and in terms of what I do, people do sometimes connect to the original stories I might have been inspired by, and sometimes they are not aware of that research at all – they just make a connection that they alone see, and that's fine with me. There’s me finding out about the world in my research, and putting that into a form of expression, then there's the viewer, who makes another connection. And to me that is a kind of completion of the whole. I do look at the things that are saddening and difficult in my work, but I'm always trying to bring that sadness into a kind of wholeness. The starting points are often things that make me frustrated with human nature, but the process of making the work is to put those things into a whole view of what it is to be alive.

That sounds almost like seeking to reach for the sublime?

I don’t know about reaching for the sublime. I suppose that people experiencing grief sometimes touch on the sublime if they allow their grief to pass through them rather than fight it – people can even have these essential experiences of beauty in grief, if they're lucky, and that's the good side of grief, if there is such a thing. The sublime is something different from emotion, though. It's a thing in itself, which is maybe about melancholia – feeling small in the vastness of the universe, and being okay with that feeling. I look at quite difficult things in my work and in the process of looking at them, I can become more able to understand them and accept them, even if it's a terrible thing.

What are you looking at right now in terms of source material?

At the moment, I am looking at the history of the witch trials within the context of the Civil War, and that came to me because of the de-humanising statements in the public realm made by Suella Braverman, and her predecessor, about refugees. I wanted to look at another period in British history when that dehumanising process had had happened, and the one that occurred to me was the witch-hunts. So, I've looked at the context of religious conflict and the economic downturn that preceded the witch-hunts. I wanted to put that into context, because usually that nasty process comes out of political instability. The process itself has involved collecting pigments from the villages where the accused women came from. I went to villages in Suffolk and picked up earths from the places where they would've walked, and I've said their names in their villages, and sometimes left little messages.

Are you essentially talking about history being a cyclical thing, doomed always to repeat?

Repetitive? Yes. There are things in human nature that mean we seem to make the same mistakes over and over again. What is sitting at the heart of everything I do, though, is what can we do to stop it when we are travelling in the wrong direction? That is the kind of optimistic side, I guess – that maybe a meditative quality can help us to better consider our decisions. Generally speaking, I think people are probably far more cruel when they're caught up in something, rather than when they take the chance to step back and consider things with distance. There are some straight up nasty people, of course, but a lot of people just end up being caught up in things, because they don't take time to step back and consider. And although in some of my pieces the starting point isn't particularly optimistic, they can conversely turn out to be very optimistic.

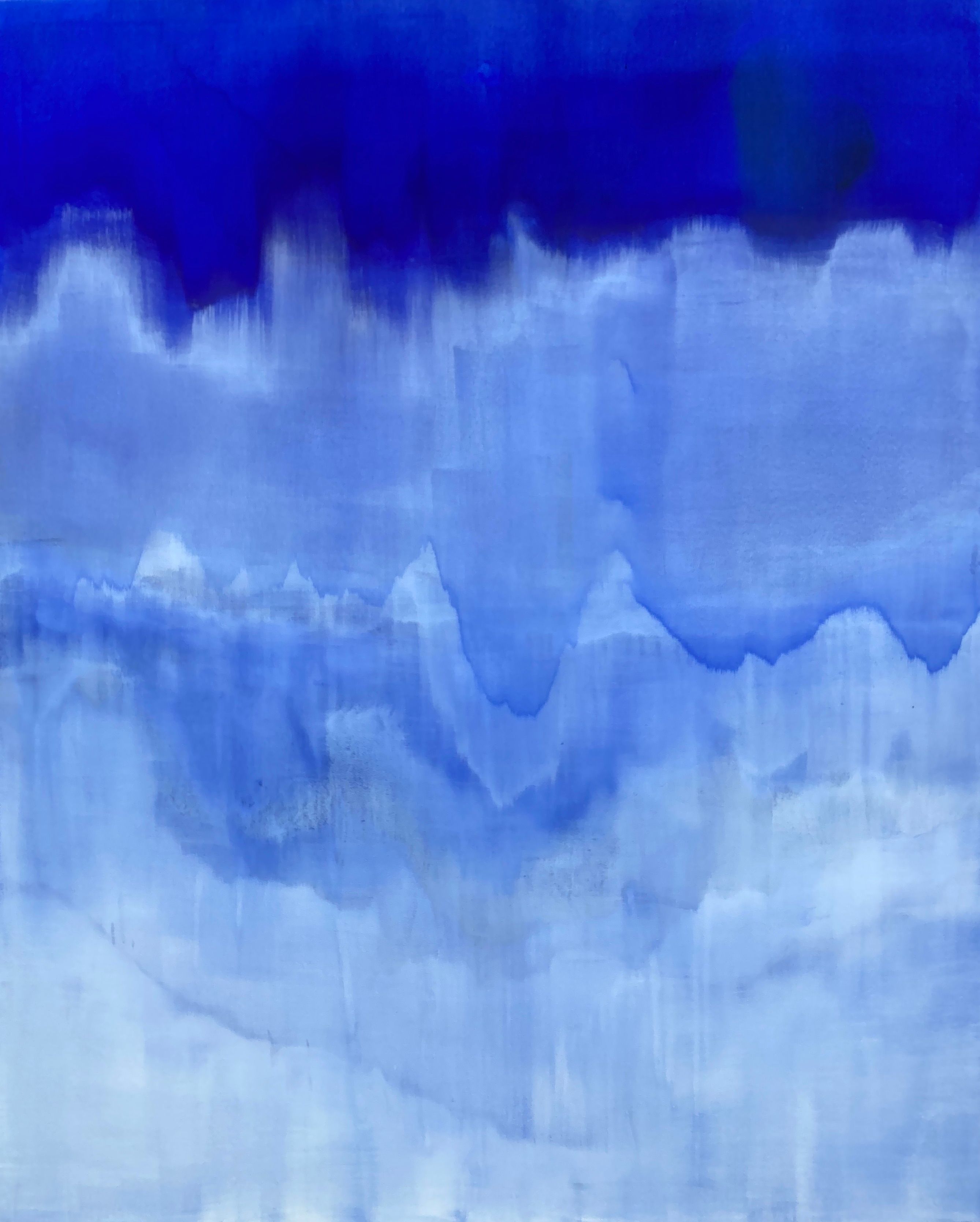

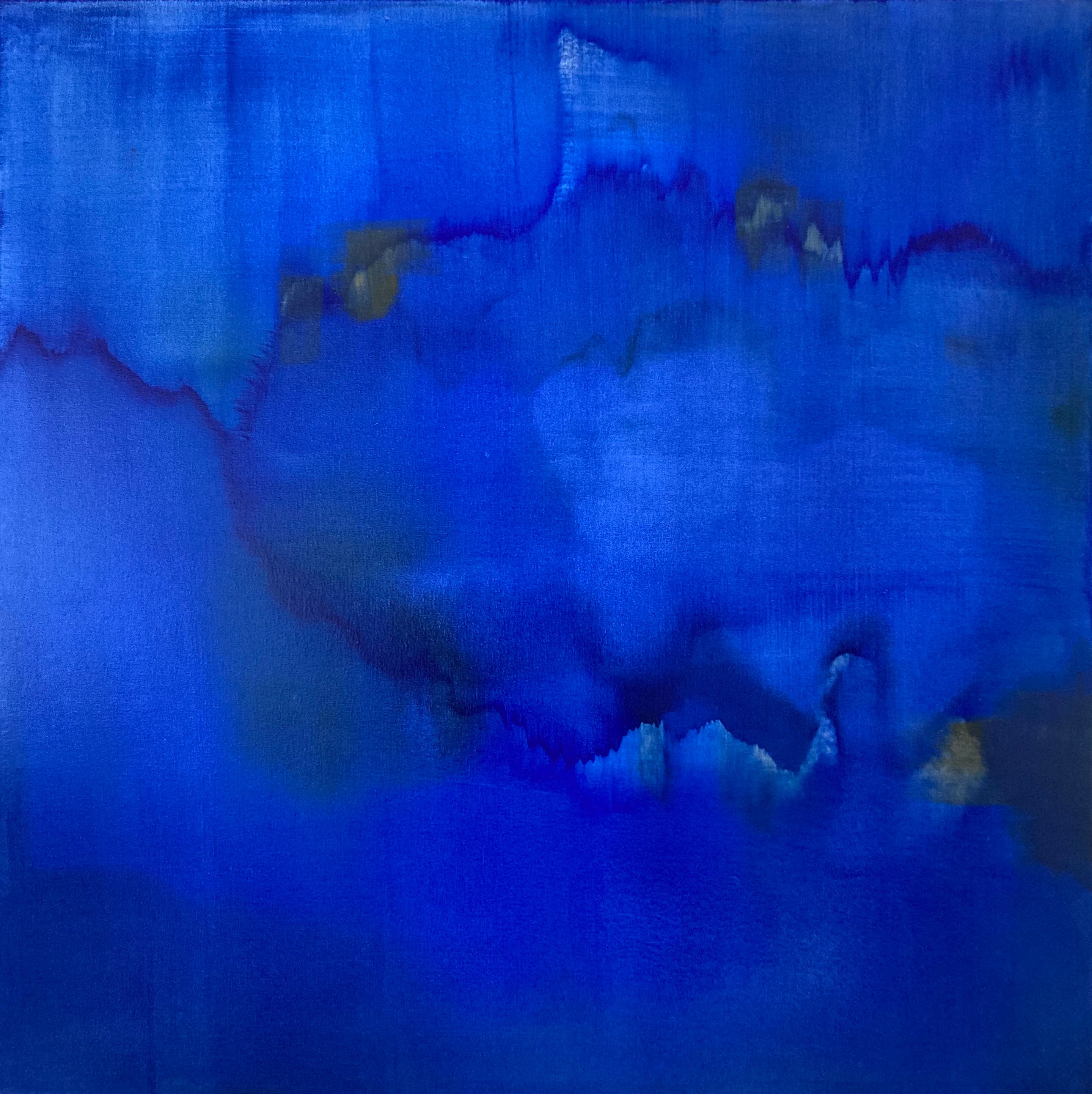

Your series Small Ports And Sea Coves feels optimistic ...

In that blue collection, I was looking at ideas about truth and lies, and that made me think about piracy and smuggling, having grown up in the Southwest of England. All of the pigments in that collection have a relationship with piracy, the southwest coast and clay. And that's the white clay of porcelain, but historically it’s transformed in the lab into this blue that mimics the genuine ultramarine blue of Yves Klein. So, when I was thinking about the idea of smuggling and lies, it led me to these quite happy thoughts that smugglers hid everything under the sea, but the tide goes out, so, ultimately, your secrets in your life will be revealed in blue, and the truth will out.

Images (top to bottom): Beneath the waves, handmade oil on canvas; Sea, Lines, handmade oil on canvas; Earth Red, handmade oil on gesso on canvas; Earth pigment after cleaning, processing and final grinding; Blues, handmade oil on canvas