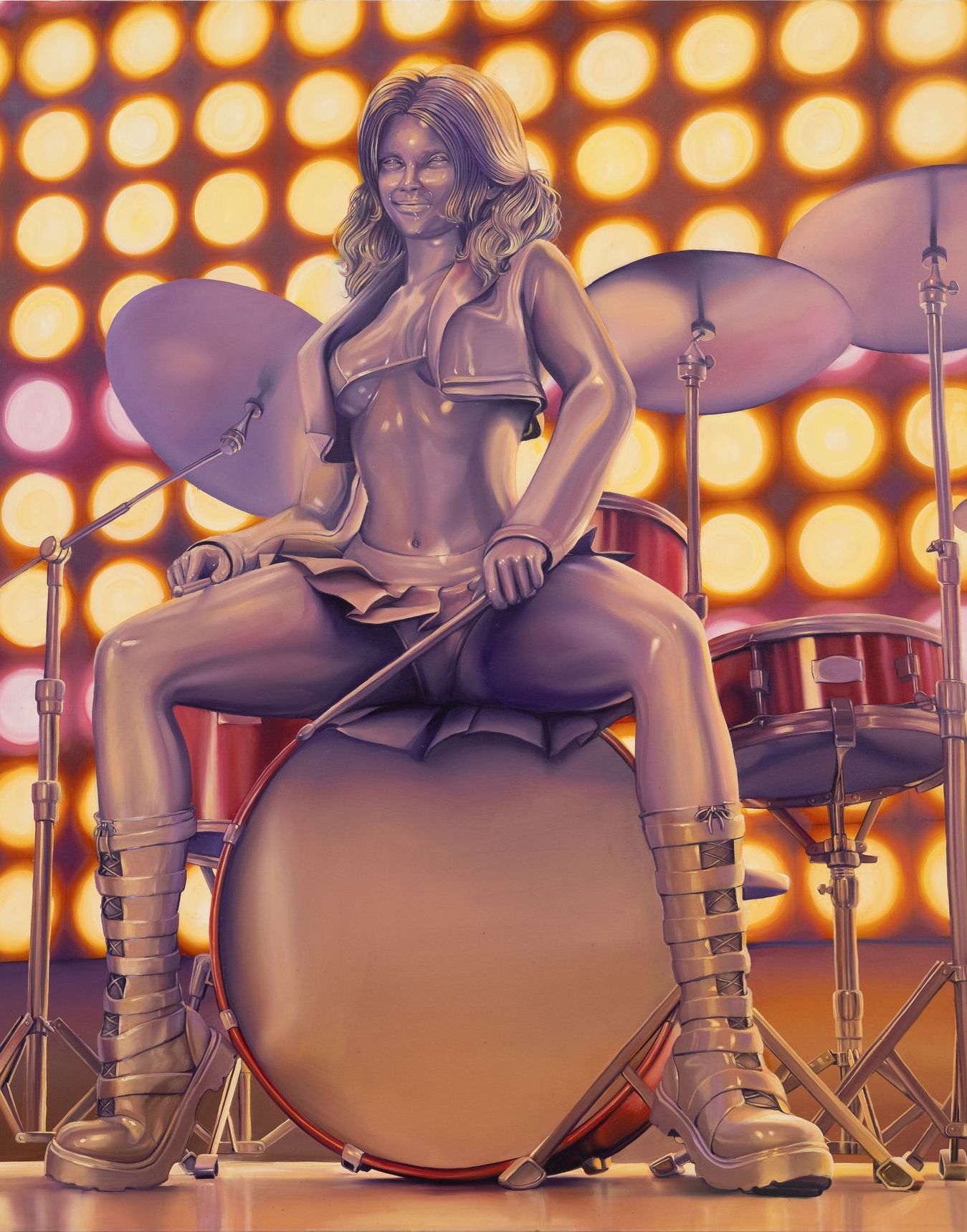

The art of New York born Emma Stern seems to invite the viewer into a curvaceous and hyper sexualised digital playground that borrows its influences from the vistas of fetish, perversion and fantasy – presenting various iterations of her voluptuous ‘lava babies’ in the increasingly fantastical and infinte environs three-dimensional gaming software has to offer those adept with the technology. It turns out to be a rather brilliant illusion, however, when those who have only seen the celebrated artist’s work online come to realise that the images she creates utilising 3-D software are actually finished as superabundant oversized oil-on-canvas paintings. Employing tools intended for game developers to create virtual female models, Stern’s work presents an entirely new twist on feminism and contemporary portraiture, simultaneously emphasising and subverting the inclination towards fetishised representations of comely women in gaming culture – combining historical notions of the muse with the likes of Lara Croft while bridging the techniques of The Masters with the lube-heavy animated sub-genres of the Internet. The latest version of Stern’s unashamedly sexy off-brand feminism is Penny & The Dimes: Dimes 4Ever World Tour – a show that explores all of these themes via a Josie and the Pussycats-esque fictional band of buxom guitar-wielding girls rocking out in a virtual stadium. Here, the artist talks candidly with Culture Collective about the inspirations behind the latest show, her love of virtual selfhood, and her disdain for feminist tropes about the male gaze.

When did you first decide to set out on the path of the artist, and where did the fascination with gaming culture stem from?

I don't feel like I ever really made a conscious decision to be an artist. I was just kind of a pain in the ass as a kid. I got myself into a lot of trouble, and I think I got away with a lot because all of the grown-ups in my life were just kind of just like, it's fine, she's just, she's going to be an artist – she'll be okay. I grew up in a pretty strict home. I wasn't allowed to play video games and was only allowed to watch one hour of educational television per day. I think because of that I pushed back quite hard, and I became a bit obsessed with the aesthetics of gaming because it just felt so foreign, and such a taboo. I've never called myself a gamer, though. It has always been more about an interest in the aesthetics of gaming, and being able to look at gaming culture as a tourist with no emotional attachment always allowed me to kind of see it as a kind of visual vocabulary, rather than something that I would associate with actual gameplay. Whenever I did play video games as a kid, the most interesting part to me was always the character design, and that kind of just stuck.

What interests you in virtual selfhood and taking on different personas?

Well, I've referred to what I'm doing with avatars as being sort of connected to the concept of the artist and the muse in terms of broader art history, and how that dynamic has played out throughout history. The first art movement that I really fell in love with was surrealism and all those guys had their muses that reappeared over and over again in their work. The way that I try to make that relevant as a female painter in the 21st century is to start referring to my works as sort of an extended portraiture project – because what is an avatar, if not a self-portrait? I tend to think of my paintings as different proxies for myself, and I call the work an extended self-portraiture project, because all of the muses – all of the lava babies – I create are iterations of myself, in a way. I really love the sovereignty and freedom you can find in virtual selfhood, and I think we all engage in it. I mean, social media is all about this kind of hyper curated persona, isn’t it? And, in many cases, these social media avatars we create are almost more authentically ‘us’ than whatever body we were randomly dropped into – most of us spend as much of our time as our virtual selves as we do our actual selves these days.

What is exciting for you about the creation of virtual worlds?

To come back to the religiosity, I remember being really fascinated with creation mythology very early on, and I suppose the world creation connects to this larger idea of freedom. And it’s not just the freedom to essentially design yourself and your environment virtually, but also the freedom to change your mind about that iteration again, and again. I'm really interested in the idea of different characters and role playing, but in terms of what I am saying as an artist, I'm a big believer that you put something out in the world and you're not really in control of how it gets interpreted once it has left your domain. There have been a lot of different reads on my work. I think there's the surface read, which is, you know, hot girls doing stuff, and then there's the deeper read, and both of those are available. I try really hard not to force anything on anyone. I suppose it can be seen as a kind of escapism, and I do think that's one way to think of the work, but it's only escapism if you're really differentiating between your virtual and actual self, which I try not to do, because I don't even know where the baseline would be at this point.

Tell us about the conceptual genesis for the Penny And The Dimes show …

This show is all about a fictional rock band called Penny And The Dimes, and I got the idea for it when I went to the ABBA Museum a couple of years ago on a whim. I don't really have any strong feelings about ABBA, but I thought it was really fascinating that they basically exited public life for the most part, and yet here were their holographic proxies touring in perpetuity. I started thinking about how that was connected to the work about avatars and virtual selves that I'd already been doing and started writing a story in my head about a rock band that gets turned into holograms at the hands of a nefarious record executive. And that's the story of Penny & The Dimes, who are kind of based on my favourite film Josie And The Pussycats. I've written a short story that's an accompanying piece for the images in the show.

Your work has sometimes been described as pornographic - what do you think about that?

I mean, people love to use the word pornography when talking about my work, and it doesn't bother me, but I do think it's funny because there is not even any nudity in my work – so to hear the word pornography get thrown around is kind of interesting. I have heard the phrase porn adjacent used to describe it also, which I kind of like. I am certainly borrowing certain tropes, but to my mind there's nothing pornographic about my work. I think there is just a lack of vocabulary that we have as culture to speak about things that are a little bit sexy and a little bit horny, and I think they then fall under this wider umbrella of ‘pornographic’ because of a lack of terminology, The gamer software I use to design my characters certainly gets used by people who create 3D-porn, and I think when you're working with a tool that's designed for one thing and you are subverting it and using it for another, the flavour of its intention maybe still comes through, if that makes sense? The arena of software and gaming is very male, and I'm very interested in subversion of that – I kind of feel like a hijacker in a way, which is fun. I do think that the minute something's a little bit playful and a little bit cheeky in our culture, it starts getting called porn, and then people start talking about the male gaze, and I despise that term.

Why do you have an aversion to discussions of the male gaze?

Well, I think it assumes the default viewer is male, and I think most discussions of it are connected to kind of a very outdated kind of feminism that just doesn't really sit well with me – this notion that if something is sexy, then it's in reaction to some hypothetical male audience. If there is one thing that I really try to kind of push up against, it's that I suppose. What I find interesting is that young people don't need this explained. There is a whole generation now that aren't so obsessed with sex, and when I say obsessed with sex, I mean that they're not obsessed with not liking it, or obsessed with being offended by it. It's not taboo any more, and there's nothing to be offended by. There is also this much more relaxed attitude towards gender in general. People have called my work ironic sometimes, and I think that is a total cop out, because the way I define irony is a lack of authenticity, but I really authentically like the images I make. I've also heard someone say that my work is ironically misogynistic, and I think that's just a way for someone to grant themselves permission to like something – I mean, can a woman even be misogynistic? All of these terms need a big update if I'm being honest, but I'm just here to make paintings. I'm not here to update anyone's vocabulary.

Penny & The Dimes: Dimes 4Ever World Tour opens at Almine Rech on Sept 6th. Find out more here.

Images (top to bottom): Penny, Brandy, Destiny & Daisy (2023); This One's For You (2023); Totally Amped (2023);, Daisy (2023); all images courtesy of the artist and Almine Rech.