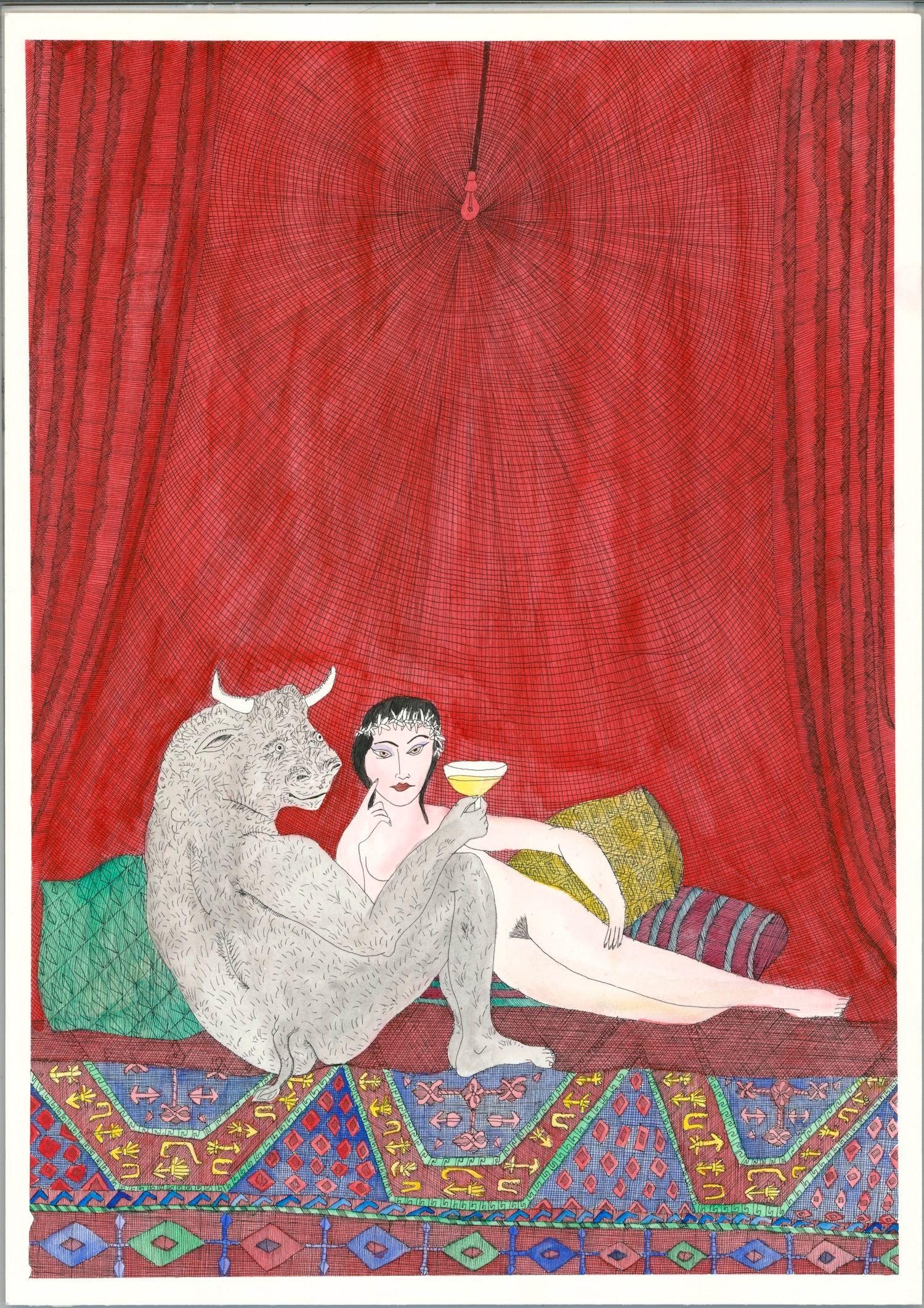

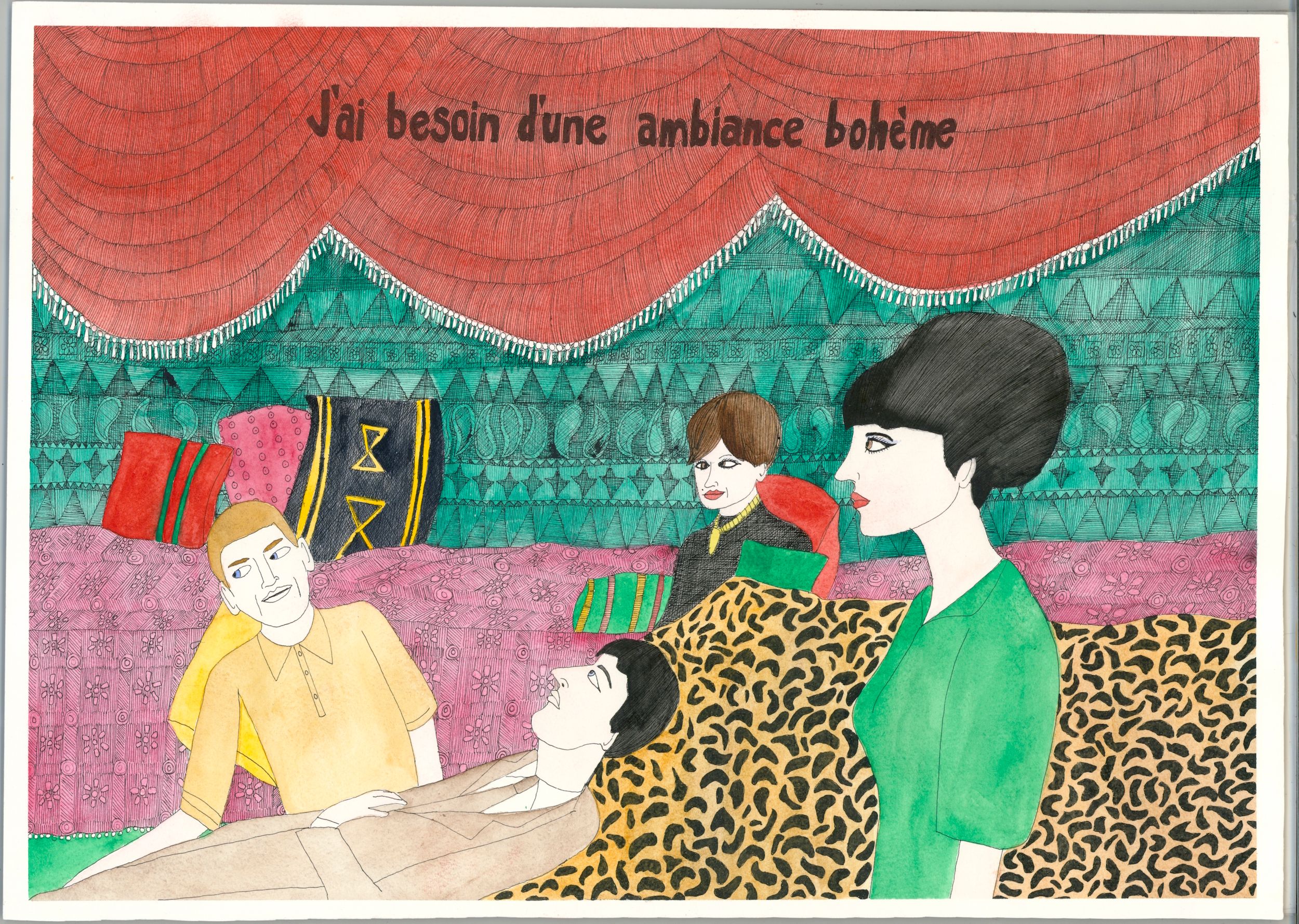

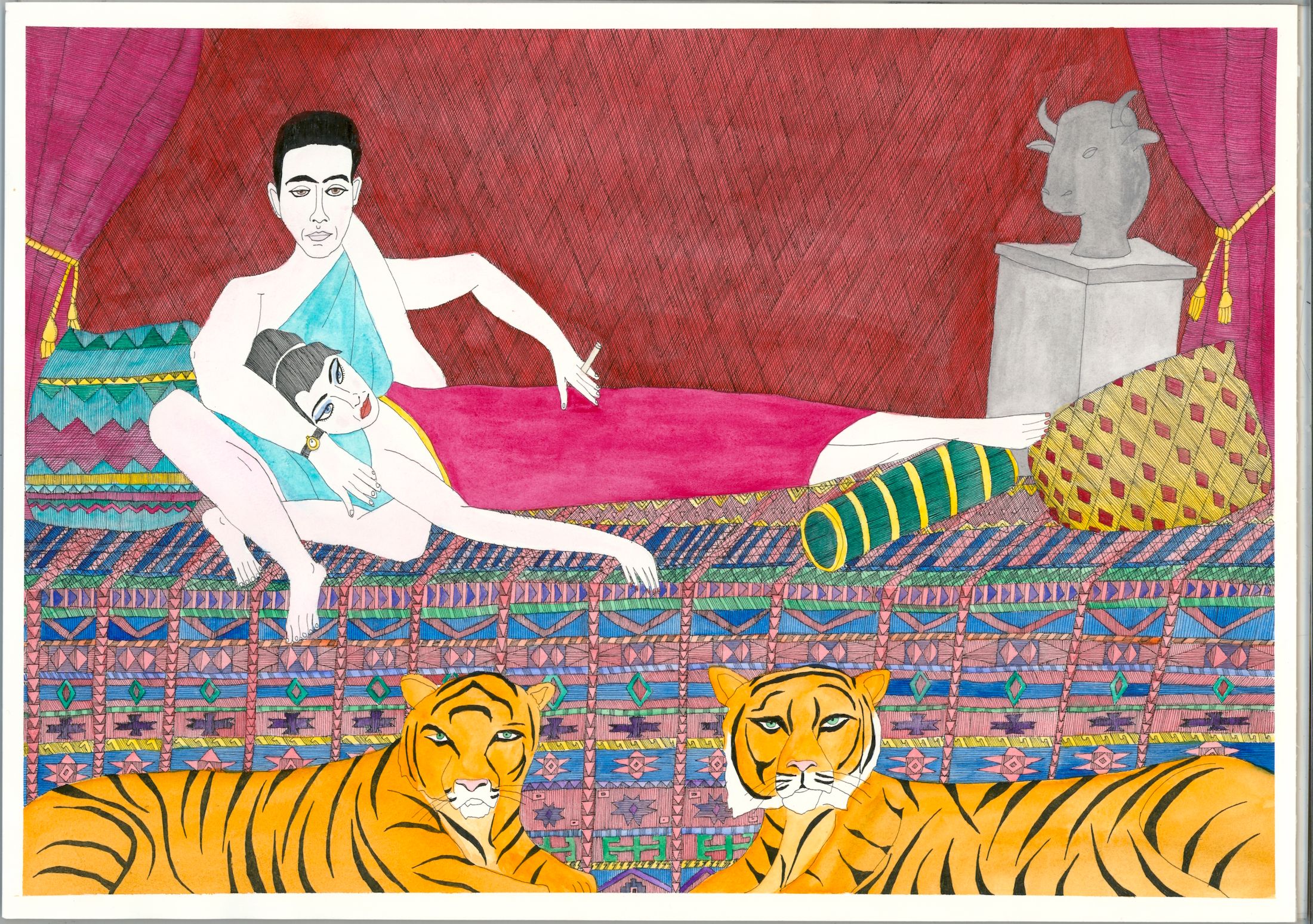

Robert Greene is an artist you will more likely know as Robert Rubbish, one of the founding members of the notorious art collective LE GUN, who have blazed an influential trail across the alternative scene since their mid-noughties graduation from The Royal College of Art. Although Greene has not quite yet shed his infamous non de plume, he tells us it's a sobriquet he intends to quietly bin when we meet to discuss a new series of his works, which explore the cultural fascination with “bohemia”, and those mysterious characters who adopt its somewhat opaque ethos as a lifestyle choice. Entitled L’Angle du Hasard after a fictional head shop featured in auteur Jacques Rivette’s 12-hour underground classic OUT 1, Greene's latest show is an ardent celebration of bohemian indulgence, taking into its sway experimental cinema, the surrealist movement, and sumptuously excessive interiors – cue Robert de Montesquiou daydreaming with a baby tiger, James Fox’s cockney villain trying to endear himself to a moody Mick Jagger, and the minotaur of Montmartre lounging in a resplendent Parisian boudoir. Here, the distinctive artist talks to Culture Collective about conquering childhood dyslexia, embracing artistic evolution, and the unbridled joys of escaping into a world of one's own making.

Can you recall what set you out on the path of the artist?

I was very dyslexic as a child and school was a bit of a nightmare, so I just drew like mad. As a kid, I would sit in front of the TV and draw anything on the screen, and I just remember it always being a very pleasurable experience to draw – I very much had that sense that this was what I enjoyed doing, and what I was supposed to do. I think I always wanted to go to art college, and be an artist, but when I left school, I didn't have any qualifications, so it was a very weird journey to get to there. I was in my early 20s, when I did a two-year GMVQ art course, and got the qualifications I needed to wind up at The Royal College of Art. That's where I met the other artists who became LE GUN, which was great.

How formative was LE GUN in terms of you evolution as an artist?

In lots of ways, I probably learned more working with my friends after art school, than I learned anywhere else, making large installations that were almost like stage sets and imagined interiors. And, when we started, there was nothing else like that around. I think I am more content to work on my own now, though, rather than work in a group. In the last few years, my work has really evolved, and a lot of what I do now is to create a scene containing snapshots, or composites, of certain characters or myths that may or may not have happened. In any artwork I create there is usually a craving of creating a space or a scene that I can kind of inhabit – especially if it's an interior, and in a sense, they're all kind of interiors.

What would you say the interiors, or spaces, you have depicted in this show explore?

This show is exploring my idea of bohemian spaces, or maybe my cliché version of them. And I suppose these imaginary spaces are interesting to me because 'the bohemian' is still considered so exotic, and is kind of beyond class. Henry Miller has that line at the beginning of Tropic of Cancer, which, to paraphrase, says something like, 'I’ve got no money, no job, nowhere to live. I'm the happiest man alive.' And I suppose when you've got a lot of money, it’s kind of a similar thing to not having a lot of money, you know? Just in the respect that you aren't worried about certain things. I mean, you can be working class or aristocratic, and be bohemian – it’s just a bit of a mysterious and unreal space, and a bit of a rejection of the capitalist system. I love that quote in Nicolas Roeg’s Performance when James Fox’s character says to Mick Jagger “I need a bohemian atmosphere” – because I think we all kind of need a bohemian atmosphere sometimes. That actually became the inspiration for first picture I made for this show – it’s kind of a beautiful scene in the film, before this criminal character hides out in a bohemian nether world.

Was film a key inspiration for all of these works?

A lot of the show references films, but some of the figures are real, or just from my imagination. The antique dealer Christopher Gibb features in one of the pieces – the man they called The King of Chelsea, who was kind of responsible for bringing a Persian aesthetic to interiors in the 60s. Another features the French film director Jacques Rivette, who made the film Out 1, which is a very bizarre twelve-hour-long film. I have always loved those scenes in French New Wave films, where someone will walk into a space, and there's all these mysterious people who are lounging around, and they're just sort of other.

Would you describe your work as playful?

There’s definitely a playful element to my work. I think making art, is essentially play. No artist can deny they are playing with their crayons. And I'm sure the desire to create art or music comes from a state of being where you are enjoying something. For me, I like that sense of trying to project a picture from my mind to paper, or whatever, and the joy of what you can actually achieve within the obvious limitations of the process – a lot of my work is just about the joy of people, and the joy of experience. I do feel there's a real need in me to draw, and if I haven't done it for a couple of days I feel a bit flat. There was a composer on the radio the other day, and a young kid rang in and asked, what advice have you got for me, because I want to be a musician. And the answer was, you have to ask yourself: do you really need to do this? If yes, then do it, but if no, then it should be a hobby, because you’re not really going to be driven – it kind of all boils down to that.

What kind of feelings do you hope the show will engender in the viewer?

I honestly think that is a great question, because I wouldn't actually ever think about what someone might think. It’s quite funny, because someone came up to me at the opening, and was like, so, what's that lemon about in this picture? There's a picture in the show that is supposed to depict Max Ernst with one of his wives, and a tiger – Max is holding a lemon, and this person had been earnestly trying to figure out what the significance of the lemon was. The picture was made two years ago, and I really have no idea what was going on in my mind. I suppose with most art, if you don't have the context of a press release or exhibition statement, you wouldn't ever know what links all the work together, right? I mean, art criticism seems to actually have a lot to do with how people view an artist within the canon of art history. If you look at the way David Sylvester lauded Francis Bacon, for example, then it was probably one of the reasons that Bacon had a lot of stuff happen for him – because there was someone on-board who was really getting it, and communicating what it said about the human experience in very long interviews. (Laughs) I like to think my work is a lot more fun, though, obviously.

Where would you place yourself in a lineage of artistic tradition – would you describe yourself as an outsider artist?

I wouldn't quite see myself as an outsider, but I wouldn't see myself as an insider. I'm not in the gallery system, or anything, and I don’t know if that is good or bad, but if I can survive in the way I am then that's fine – the main thing is to make work. I suppose I see myself coming from a tradition that is similar to people like George Grosz, but not being as political, or maybe Edward Burra? I tend to like artists that create a sort of narrative figurative art, if that makes sense. Another big influence would be Andrej Klimowski, who made these really great film posters for films like The Omen that would be used in countries where they couldn’t use American film posters. I suppose there’s always this thread in my work of creating a scene that a viewer can step into, or create a narrative from – it’s kind of fun to be able to make your own world, isn’t it? I suppose that writers, poets and artists all kind of live in their heads. Maybe that is where Bohemia really exists.

L'Angle du Hasard is at James Jackson Gallery until June 26th

Find out more @robertrubbish