Enam Gbewonyo is a London-based textile and performance artist, whose multi-layered work places womanhood and the spectre of colonialism under the microscope in a conceptual practice intended to engender both personal and collective healing. Employing the craft of weaving as a time-portal, she creates works that present uncomfortable truths about the invisibility of the black body in western culture, while usurping traditional beauty tropes. Gbewonyo has exhibited with galleries and institutions all over the world, and has delivered performances for the likes of Christie’s, The Henry Moore Institute and 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair Marrakech. She is also the founder of the Black British Female Artist (BBFA) – a platform that supports emerging black women artists’ careers. Gbewonyo is currently showing at Body Poetics at GIANT gallery in Bournemouth, where she has created a series of site specific works in call-and-response with fellow artist Senga Nengudi, and in the group show Rites of Passage at The Gagosian, London. In this interview with Culture Collective the artist, discusses her passion for transforming everyday materials into political artworks, and tells us why her work as a healer has bought her full circle.

In the past you worked as a designer in the fashion industry in New York, and you have also worked as a teacher – how have these experiences shaped you as an artist?

I’ve done a lot of different things, but everything that I've done has definitely led me to this point. I always gravitated to textiles at college, and it was the sense of tactility that I really connected with. At the time, I was too young to have been able to contextualise it, but I realise now that my passion for textiles really is inherent to who I am. The heritage of my Ghanaian tribe is weaving, and there is also a strong tradition of storytelling and performing. I've kind of come full circle because weaving is so central to my art practice, but I also create performance and films – so it is all very much interconnected. When I was working in America, most people didn't even know where Ghana was. I wasn't really cognizant at the time, but I look back now and realise that when I was working as a designer, the silhouettes I was drawing were all white women. I can see how that was kind making my own self invisible, and my work now talks about that, and my own journey of self-discovery.

How key is that notion of enforced invisibility to your work?

This feeling of being invisible is very much key in the history of the black experience, and is deeply ingrained. I'm trying to break those cycles in my work, and to heal from a subjugation that I hadn't even really understood – one that had boxed me in to being something that I'm truly not. When I moved back here from New York, I wanted to be a teacher, but very soon I realised that actually for who I am as a person and how I want to be able to affect change, I couldn't do that in the construct of education as it stands. It was actually my brother that kind of sparked the plug towards devoting myself to my art. In creating art, I began to think about how I could help other black women heal. It starts with looking back, and going through the history of empire, colonialism and slavery. I am interested in how I can most authentically be myself, and the work I create is part of that journey.

What drew you to hosiery as a key material in your practice, and what does it represent symbolically?

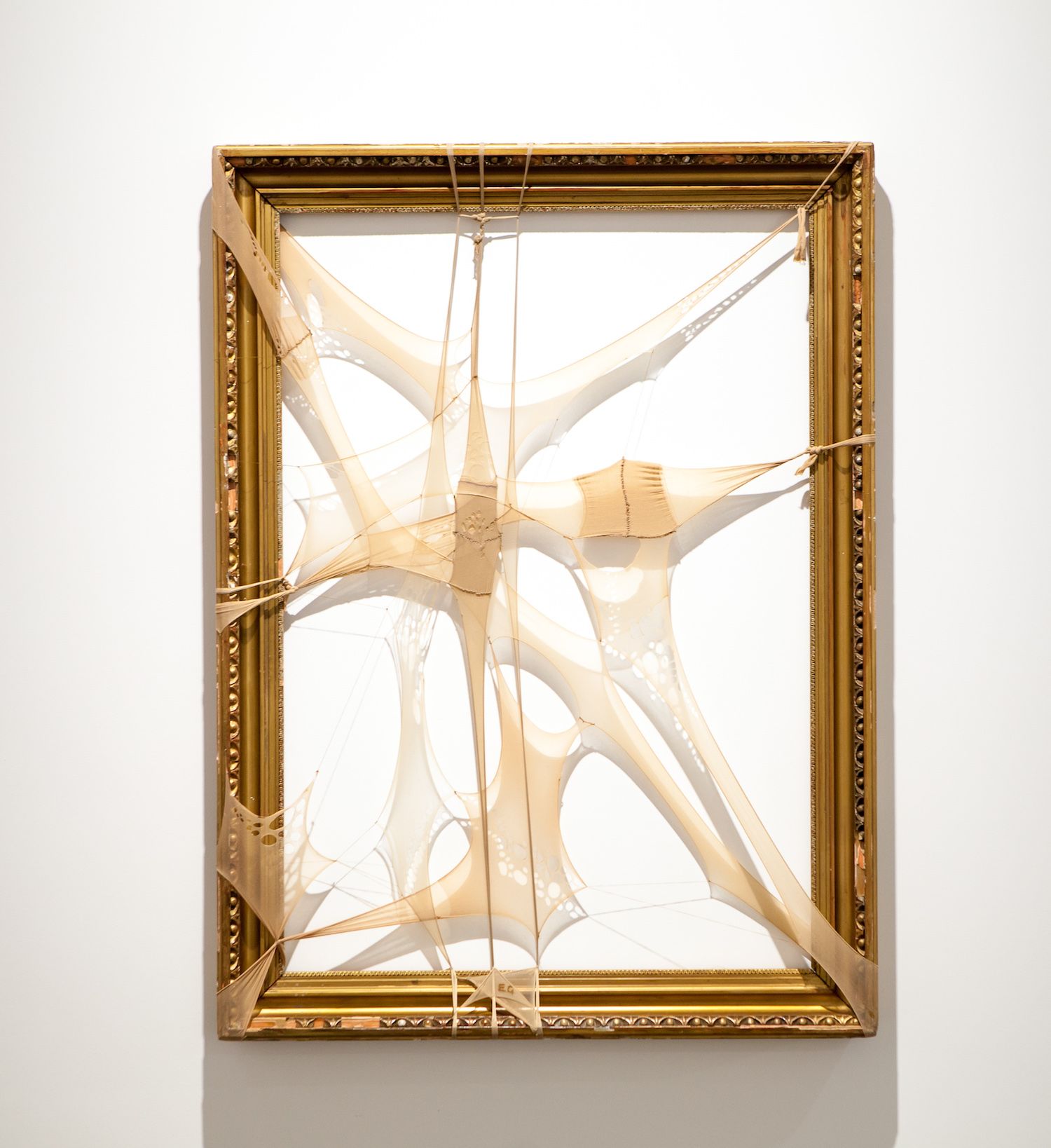

I started seeing a lot of brands making tights for women of colour, which got me thinking, how long has it taken us to get to this point of inclusivity? I started from a point of research – accessing the V&A archives, looking at the advertising around hosiery and tights, and where blackness, or black women, fitted into that. It’s about looking at where this history intersects, but also delving deep and looking at its relationship to beauty standards. I'm looking at the fashion industry and the fact is that nude tights historically are very much a product for white skin – so yet again that makes black women invisible, and undermines our femininity and sense of worth. I began exploring this idea, and then it became this bigger animal, because I started looking at the ballet industry and how black ballet dancers had to dye their own tights, which took me to looking at the elitism and racism within the arts world.

Do you feel a viewer needs to know the context to understand the work?

It's not necessary that you need to know the context, but I think in some ways it does translate just because of the fact that, you know, it's hosiery product, so you immediately think of femininity. The work has this sense of delicacy, but it’s also about the stretching of fabric, and the idea of tautness and tearing – with a draining emotional kind of aspect coming through. That is also where the performance aspect comes from. The performance side is a way to truly express the vulnerable, intimate element of the work. I talk about the performances in terms of creating spaces for healing, and I feel like the performance, and the film aspect we are moving into, really does that. The film aspect is creating a new space for me to tell the stories I'm trying to tell, and if they resonate, it is a really beautiful experience for me.

Why is it so important to you to have a performative aspect to your work?

In the performances, I'm either activating an artwork I've already made or creating an artwork live. So, I may be making the work within the performance, but I am always integrating dynamic movement in some way. It’s very much ballet inspired, but I integrate traditional dance, which has a history of being about healing and breath work. It's all based around this generational legacy of intimate healing. I want to kind of connect the dots, and talk about how everything we experience in the present is so tied to our history. In a sense, I feel I can create these portals that open up to the ancestral plane – this idea of accessing the great-great-great grandmother who would've existed before the idea of western beauty ideals, and kind of trying to tap into her confidence, and the values that she would've had as a black woman.

Why is that connection to the past so strong for you?

I just really want to bring that legacy through to the present, and hold onto that sense of authenticity without western ideals trying to kind of re-define or constrict them. I'm very cognizant of the fact that I'm lucky to be able to do this as my career, because I get to live and breathe this thing that is just so healing for me. I have to be very appreciative of the fact that I have so much more privilege and freedom than the ancestors that went before me. They did the work to get us here, and my part of that legacy is doing the work to move it forward a little bit. I am standing on the shoulders of giants but I can just keep pushing towards that equality.

Enam Gbewonyo is currently showing at BODY POETICS at GIANT gallery in Bournemouth, where she has created a series of site specific works in call-and-response with fellow artist Senga Nengudi. You can find out more here.

Images: (top to bottom): Performance portrait of Enam Gbewonyo from Nude Me by Michael Murawski; Bigger Than The Picture They Framed Us To See by Enam Gbewonyo, 2019. Recycled tights and cotton thread on vintage picture frame, photography by Umut Gunduz. A Cosmos Within The Infinite Black by Enam Gbewonyo, 2021. Used tights, recycled pet thread and eco- friendly acrylic paint on canvas, photgraphy by Adele Watts. Installation shot at GIANT gallery; Enam Gbewonyo. Film still from, Nude Me/Under the Skin: A Resurrection of Black Women’s Visibility, 2021