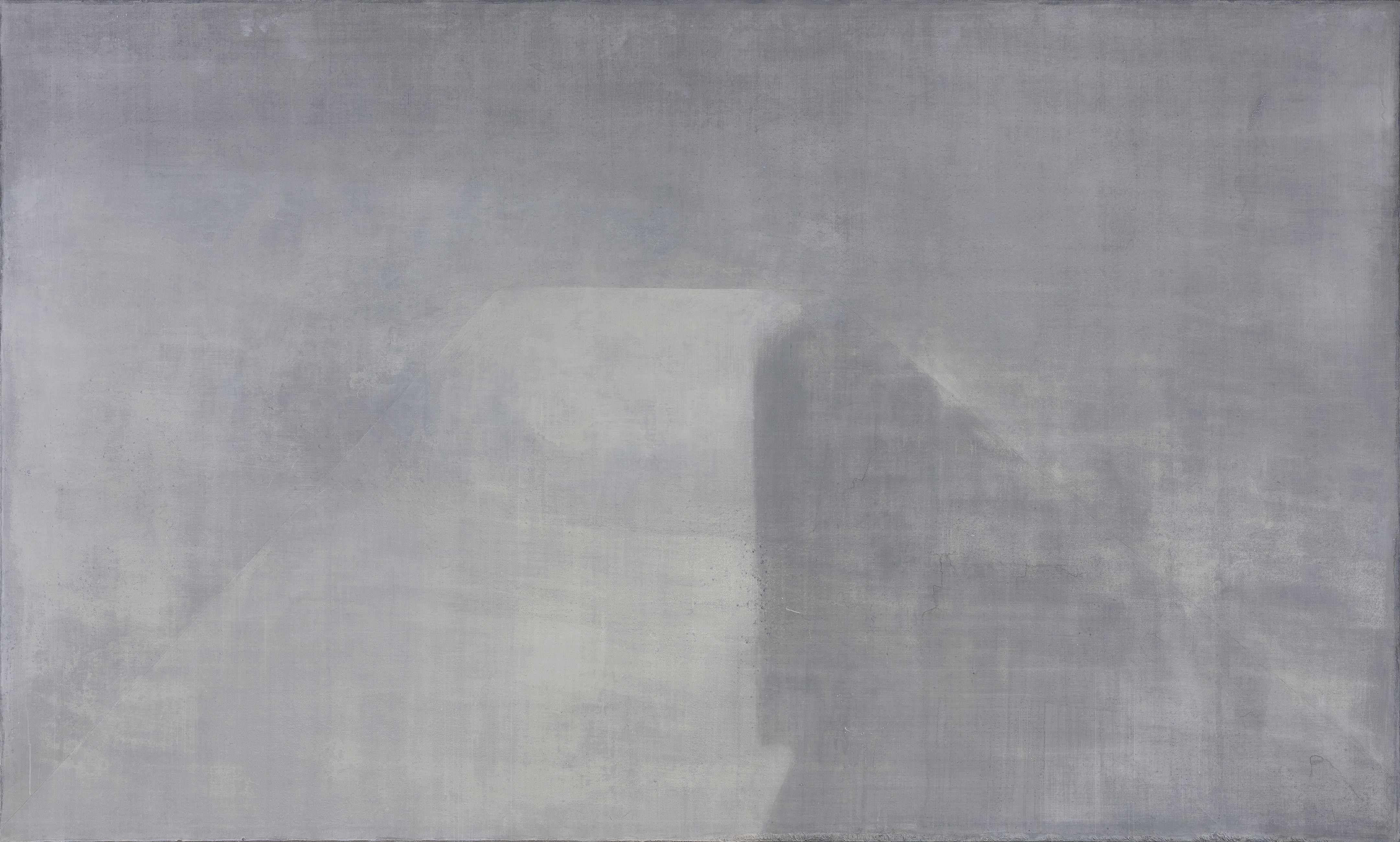

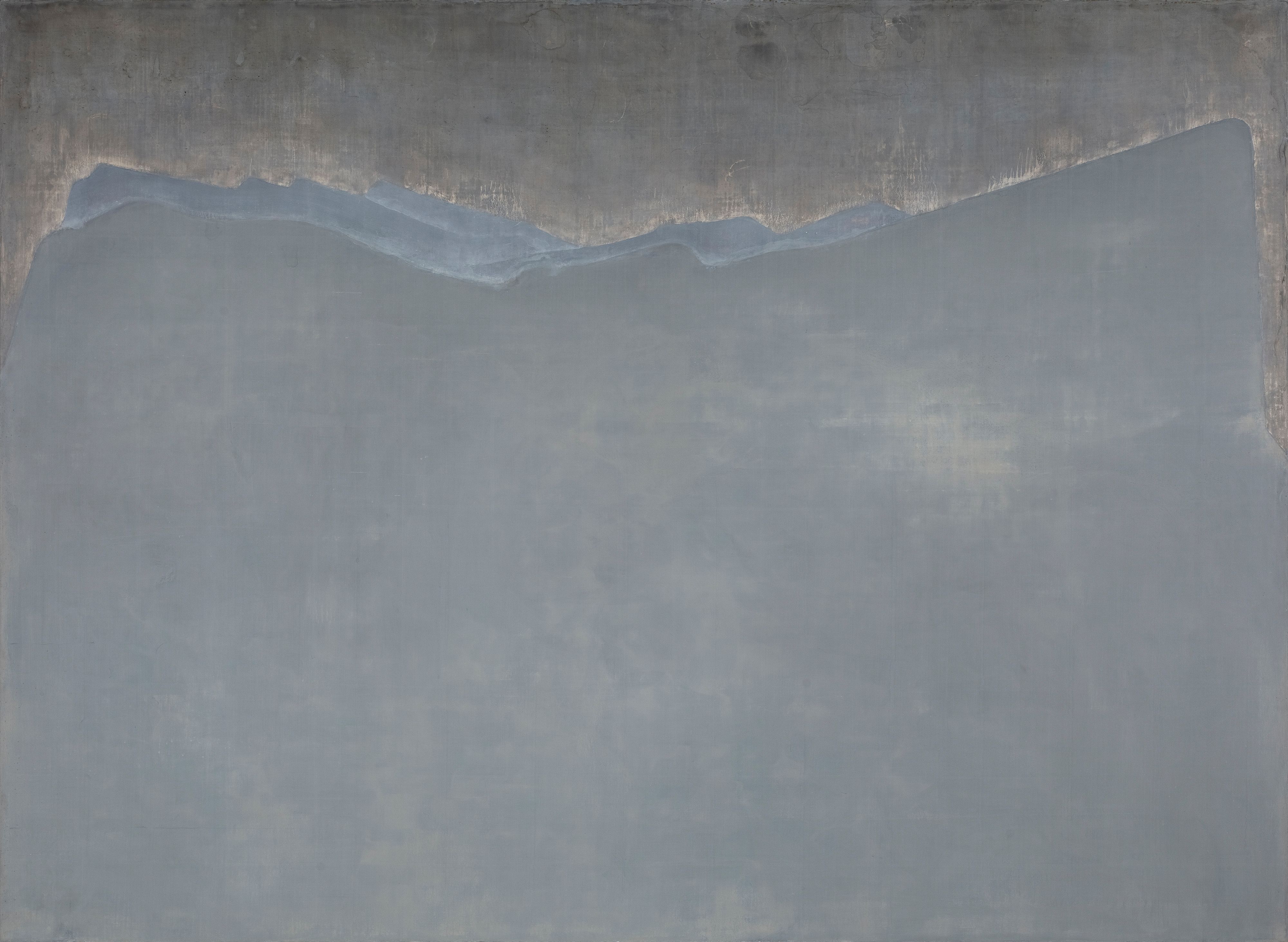

The celebrated Chinese artist Cao Jigang‘s unique artistic journey spans four decades, and he has traversed myriad mediums and techniques in that time. The thread that runs through all of his works, however, is the way in which they are characterised by a unique semi-transparency – a warm, porcelain-like texture reminiscent of jade, achieved through meticulous and deliberate layering. Expressing the concept of 'emptiness' through intentional application, Cao Jigang has transitioned towards a minimalist style, opening up a space for contemplation on the connection between heaven and humanity. From his tranquil landscapes to the chilling void of works in the Barren Cold series, the artist expresses the idea of transcending earthly confines on the ‘skypath’. His practice is a process of integrating spirit, emotions, and insights into nature – connecting with nature through art and, ultimately, reaching the path of unity between individual life and the universe, as expressed in Taoist philosophy: “Harmony between Heaven and Man, Unity of Nature and Humanity.” Despite many incredible accolades garnered in Asia, the exhibition at Bluerider ART, Mayfair, is his debut European solo show, and showcases numerous large-scale Tempera Shanshui – a practice that combines traditional Western egg tempera technique with traditional Chinese landscape (Shanshui) to result in the artist's distinctly elegant and poetic landscape style. These explorations include the monumental Altitude 4687, a four-metre-wide painting which exquisitely depicts the snow-covered peaks of the Tibetan Plateau. In this exclusive interview with House Collective Journal, the acclaimed artist shares insight into his practice and tells us why his work is intended as an antidote to the chaos of modern society.

Please can you tell us a little about your upbringing – was it a creative environment?

My parents were involved in book design, which can be considered related to art. Many of their friends were well-known figures in the literary and art circles, so, yes, I grew up in an environment rich with artistic influence. Coming home from school, it was common to see the house filled with guests, engaged in lively conversations and, at times, spontaneously composing poems or creating paintings. Our home was small, so being in close quarters was a regular occurrence. This environment had a profound impact on me.

Which are the artists that have most inspired you?

Different stages of my life brought admiration for different artists. During my time at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, I mainly studied European traditional painting and was particularly drawn to artists like Rembrandt, Velázquez, and Courbet. Their emphasis on ‘brushwork’ resonated with the expressive quality found in Chinese painting, where brushstrokes and the inherent power of ink play a significant role. Later, I developed an interest in Chinese landscape painting, with works from the Song and Yuan dynasties deeply influencing me. Artists such as Fan Kuan, Mi Fu, Ni Zan, and Huang Gongwang often served as sources of inspiration. After learning the materials and techniques of tempera painting in 2000, early Renaissance artists like Giotto, Fra Angelico, Piero della Francesca, and Uccello had a significant impact on me.

Your work is incredibly spiritual - is your studio practice spiritual in any particular way? Do you have any studio 'rituals'?

There are no particular rituals in the studio. It takes about 40 minutes to drive from home to the studio, so I usually rest a bit upon arrival to transition from daily life into work mode. This pause is essential for making the shift. Regardless of whether something joyful, troubling, or infuriating happens in my personal life, I aim to start my work with a calm, stable, and deliberate mindset. This approach is reminiscent of medieval European monks painting religious icons, working with rationality and restraint, focusing on perfecting each section of colour. I also take a moment to rest before leaving the studio at the end of the day.

Your landscapes have shifted from the realistic (your Great Wall works) to much more abstract. Was this a natural progression over the years or was it intentional?

The shift from realism to a style closer to abstraction was a natural progression, but also intentional. All human actions are guided by consciousness, and even what seems unconscious may stem from a deeper level of awareness. I aspire to paint landscapes untouched by human influence, even though such places scarcely exist today. Any sign of human presence in my work would disrupt the purity of the image.

Can you talk about your current exhibition at Bluerider ART? Firstly, where does the title 'Skypath' come from?

The works in this exhibition were completed in recent years and are more minimalist and tranquil compared to my previous pieces. The exhibition title Skypath was suggested by Ms. Elsa Wang from Bluerider ART, and I found it fitting, as it aligns well with my work. Skypath symbolises looking up toward a vast, boundless space – an alternative realm in stark contrast to the noise and chaos of modern society. Both the title and the artworks embody the essence of traditional Chinese landscape painting’s ideals of returning to nature and the philosophy of seclusion and escapism.

Why did you start experimenting with tempera?

A professor at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, who was also my college classmate, established a studio focusing on materials research at the end of the 20th century, pioneering the introduction of this concept into the curriculum of Chinese art institutions. In 2000, the studio began offering short-term courses primarily dedicated to the study and research of tempera painting. Tempera is an ancient and unfamiliar medium for most, imbued with a strong sense of religious mystique. Driven by curiosity, I joined one of these courses. My studies focused on egg tempera, which has aesthetic properties distinctly different from oil and acrylic paints. Egg tempera is water-based but also contains oil elements, giving it both fluidity and durability – qualities essential to my creative process.

Your new works combine tempera with the traditional Chinese technique of Shanshui. How long have you studied in Shanshui techniques?

I have never formally studied the techniques of traditional Chinese Shanshui (Chinese landscape painting), as I did not want to become a Shanshui painter. I only borrow certain aspects and meanings from Shanshui art. Formal training would have constrained me, as traditional Shanshui painting has numerous rules and conventions that I do not wish to adhere to.

How difficult was it to create a fusion of these traditional methods? What were the difficulties?

When I first attempted to integrate the essence of landscape and Chinese Shanshui into my work, I encountered challenges related to materials. Oil paint lacks fluidity; even with the use of significant amounts of medium, it still retains a certain viscosity. After learning to use egg tempera, my painting style underwent a significant transformation. The water-soluble nature of tempera allowed me to achieve a fluidity similar to that of ink wash.

How do you hope viewers respond to these works?

I am uncertain how viewers will perceive these works. They are neither landscapes nor traditional Chinese Shanshui paintings. My hope is that when viewers look at these uninhabited, silent scenes, their imagination and contemplation are sparked. The large expanses of negative space in my paintings are designed to invite various interpretations and thoughts.

Standing in front of the large-scale Altitude 4687 is like being drawn into the scene. Is there a spiritual effect intended?

Standing before a large-scale painting can give the viewer the illusion of being absorbed into the artwork, a characteristic common to expansive works. When viewing Altitude 4687, one might feel drawn into the piece, while simultaneously experiencing a psychological resistance to entering the cold, lofty space that evokes the phrase “high places are always cold.” Perhaps this is a unique experience?

What is the largest work you have created?

One of my significant works is a four-metre high and 7.2-meter long painting titled Guangling Melody. It was inspired by the ancient Chinese legend of the Guangling Melody and the tale of the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove. The piece depicts a colossal mountain peak, serving as a symbol of an exalted spirit. I am particularly fond of creating large-scale works. Painting on a grand scale induces a sense of excitement, with increased uncertainty and chance, which is one of the reasons I enjoy it. Large paintings demand more energy and require me to engage fully and channel all my effort. These big works hold greater importance for me, as they often represent what I am most compelled to paint at the time.

Who is the perfect viewer of your work?

I consider anyone who comes to the exhibition to view my paintings a valuable audience member, regardless of their opinions on the works displayed.

What environment would you like to see your work exhibited?

I am open to exhibiting my works in any interesting space – be it an ancient castle, a medieval church, a contemporary minimalist gallery, or even an 18th-century Rococo-style building. I am particularly intrigued by the relationships that might emerge between my works and the unique atmosphere of each space.

Cao Jigang: Skypath, runs at Bluerider ART London, until 31 December 2024. For further information visit here

Images (top to bottom): Altitude 4687, 240x400cm, Tempera on linen, 2022; Barren Cold 9, 160X300cm, 2021, Tempera on linen; Cool shadows, 140X192cm, Tempera on Wood,2023; Vertical face of mountain, 195x270cm, Tempera on linen, 2022; White U-Shape, 175x250cm, Tempera on linen, 2023.