The archive of the photographer Derek Ridgers is possibly unparalleled in terms of its documentation of post-war British subculture, taking into its sway punk, the new romantics, the acid house boom, and much more besides. Over almost five decades, Ridgers, whose work graces the likes of The National Portrait Gallery, has brilliantly captured the people at the heart of every significant cultural explosion in the UK, both known and unknown, with all the strange anomalies that have existed somewhere in-between. Ahead of his inclusion in a major show show at Somerset House this October entitled Horror Show, Culture Collective caught up with the image-maker to discuss portraiture, shooting the outer edges of youth culture and how subcultural expression has changed beyond recognition in the modern era.

Can you recall the first images that turned you onto photography?

If I’m honest, I think it might have been when I went to see the film Blow-Up in 1967. It took me a long while to realise this but I think it had to have started there. I wish I could claim it was something more meaningful but it probably wasn’t. Even then, it was still getting on for 15 years before I picked up a camera and seriously thought I might want to become a photographer. But the seeds were planted with that film. It was the lifestyle that appealed. At the time, I actually had ambitions of becoming a painter. I always liked to look at photographs but had zero interest in taking them myself.

What made you want to pick up a camera and shoot what was going on around you?

It wasn't really a ‘what' more of a ‘who’. The who was Kim Mukerjee, boss of the advertising agency I worked at in 1973. I was an art director on the Miranda camera account. Kim suggested I take one of the cameras home with me, use it and get familiar with it so that I would be able to produce better ads for it. At the time, I had a partner and a small child and our only social life was going out to gigs and music shows. I took the camera along with me to some of them and often forced my way to the front and pretended to be a photographer. Being right there at the front, sometimes even in the photography pit, only feet away from the performers, was really quite exciting. But at that stage, I was still very much an amateur, far more interested in the music than the photographs I was taking.

Do you think there will ever be another moment like the punk moment?

The thing about punk and to some extent most of the British subcultural youth groups of the latter part of the twentieth century was that they were able to go through a period of gestation, and get a proper toehold, before they were exposed, via newspapers and TV, to public scrutiny and comment. In the case of the teddy boys, mods and skinheads this might even have been a year or two. By the time of the punks and the New Romantics, it was no more than a few weeks. In the age of social media, if anything happens now, it could be just a few hours. Whoever it was that first said "a lie is halfway round the world before the truth has got its boots on” must have had social media in mind. Nothing significant can take place away from the public gaze these days and it can often have a smothering and negative effect. There is seldom much room for nuance on social media.

What for you is the most profound moment in subculture, and why?

For me it would have to be the rise of the counter culture in the mid to late 60s. Characterised nowadays as The Hippies. It was profound for me simply because I was at the right age to find it so. My entrée to into that world was the 14-Hour Technicolour Dream, held at Alexandra Palace in April 1967, just one month after the film Blow-Up was released. I was still a schoolboy and it was the first time I stayed out all night. Pink Floyd, Soft Machine, Sam Gopal and John’s Children played. Yoko Ono did her Cut Piece thing. I’ve lost it now, but for years I kept my little bit of that model’s dress.

How would you describe your photography, and what would you say you are always trying to reach for artistically?

Most of what I do would broadly fit into the category of portraiture. Even when I’m shooting fashion, I approach it in essentially in the same way as I do portraiture. It’s all just driven by my interest and curiosity about other people. Artistically it’s extremely simple. I just see myself as a conduit. All the meaning in my photographs comes from the people themselves. I try desperately not to get in the way of that. If any of my photographs are not good enough, it will usually be because there is too much of me in the equation MY approach hasn’t evolved much at all. As soon as I started to take myself seriously as a photographer - around 1981/82 - my approach has remained virtually identical. I’m drawn to people who look good and have done interesting things because, more often than not, their story will be written on their face. As a photographer, I don’t have to add anything, just metaphorically keep out of the way.

Why do you think you have always been attracted to subcultural expression?

I'm an only child. I grew up in a sleepy, boring suburb of West London in the 1950s. Heston was a place where nothing much ever happened. It seemed like a very small world. My family consisted of my parents, my grandmother and me. That was just about it. We didn’t even have any pets. My parents were loving people, but I realise now that they were both psychologically wounded. My father by the Second World War and my mother by being adopted, and then, soon afterwards, by losing one of her adoptive parents. Art school showed me there might be a lot more going on in the world and, eventually, photographing interesting groups of people allowed me, vicariously I suppose, to imagine I was much more interesting myself.

What do you think you have learned from the documentation of subcultures over the years in terms of identity?

I think, primarily two things. One, that objectivity isn’t really possible. When I was photographing the skinheads in particular, I tried to be completely objective and keep my own thoughts out of it. I realise now this is impossible. And secondly, one never really understands one’s own motivations. Even if you think you do, you’re almost invariably wrong.

How do you think the smartphone era has affected photography both positively and negatively?

In the ‘60s (thanks, in part, to Blow-Up) there was a real sense of photographers being something special. Professional camera gear was extremely expensive and there was a sense that the photographers themselves were only one notch down from rock stars. It was almost exclusively male urban elite – who were highly paid, mostly drove sports cars and were usually surrounded by beautiful women. When I was an art director in the ‘70s, I worked with a few photographers who fitted this stereotype almost exactly. During that time I only worked with one female photographer - Jeannie Savage. She also drove a sports car and was surrounded by beautiful women too. The exception that proved the rule, I suppose. The era of the smart phone has changed all that. Everyone can take photographs and, if they want, everyone can now be a photographer. Nowadays getting paid is the hard part. Really the only groups of people that the smartphone has been deleterious to are the police and professional photographers. Nowadays whenever something important or truly dreadful happens (I’m thinking of the death of George Floyd here) there’s always someone around to record it. No one has to wait for the professional photographers to turn up. I think the pluses far out way the minuses in this situation.

What is its effect on the artistic medium of photography?

I think it’s pushing the overall standards up. When I started, you needed just two things to become a professional photographer – an expensive camera and the confidence to seek the work. You didn’t really need talent and there was enough work to keep everyone happy, and if your work was good enough, everyone would see it. These days you don’t need a professional level camera - the hobbyist ones are often just as good - but there is a lot less paying work around. And, with Instagram, it’s easy enough to get your work seen but much harder for anything to stick. In the days when magazines and newspapers were the primary way of people consuming photography, one always had a few precious seconds to make an impact. These days, you blink and it’s gone.

The Derek Ridgers archive is available as Limited Edition prints via Derek Ridgers Editions. To commission Derek please contact Unravel Productions.

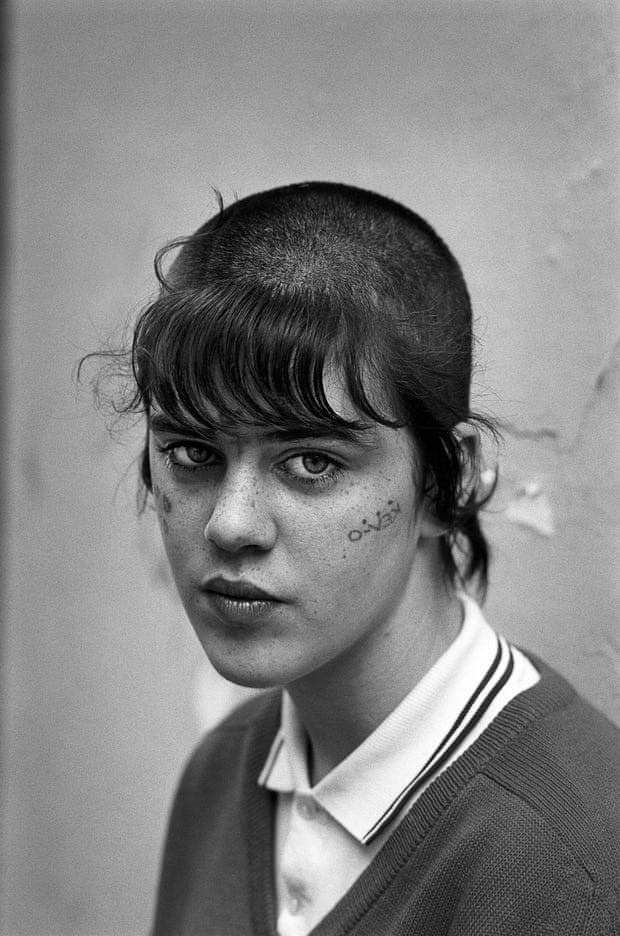

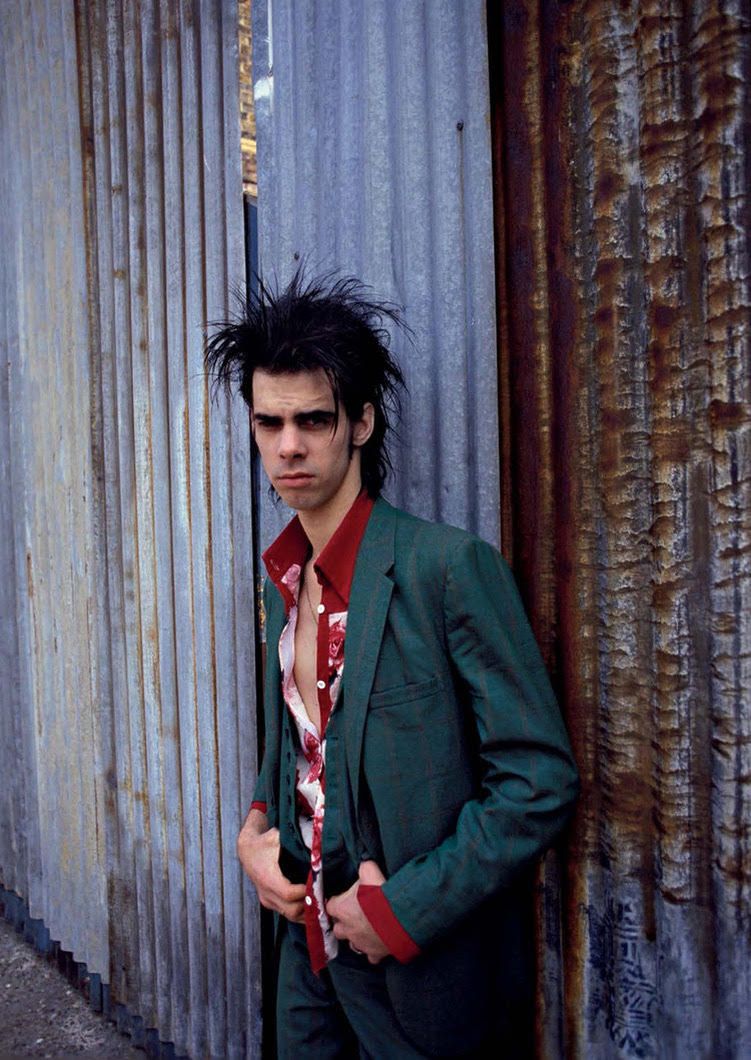

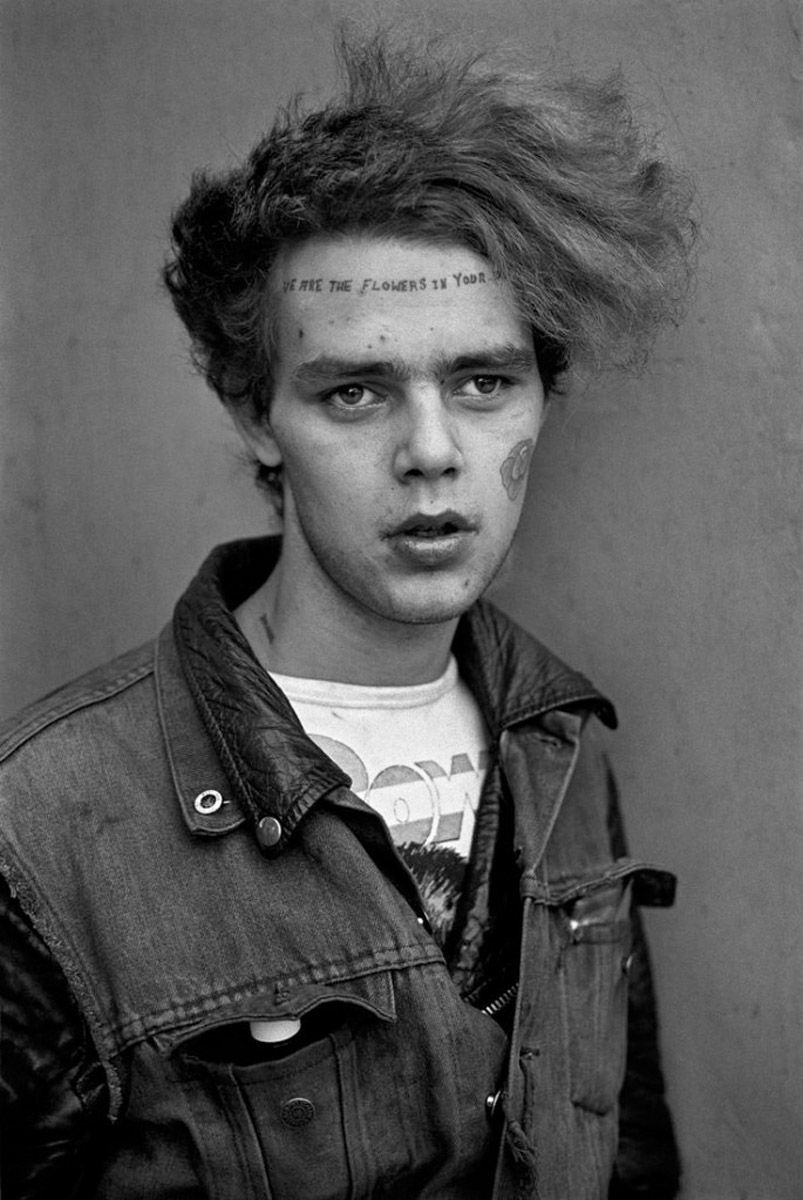

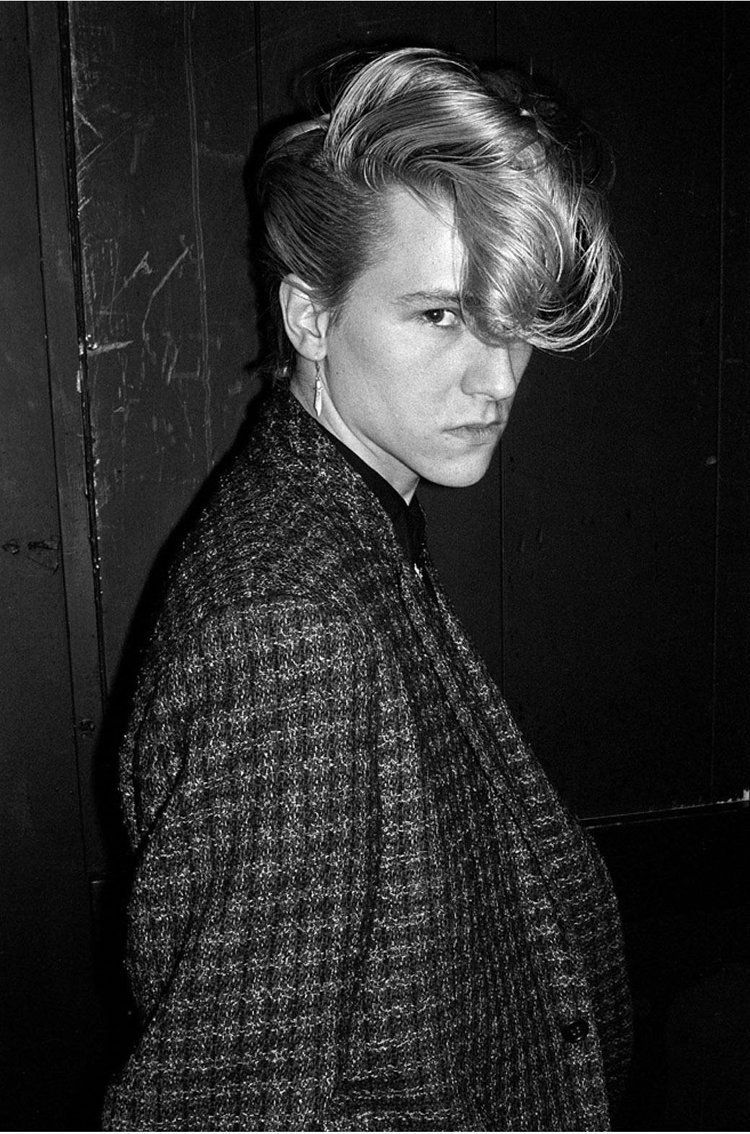

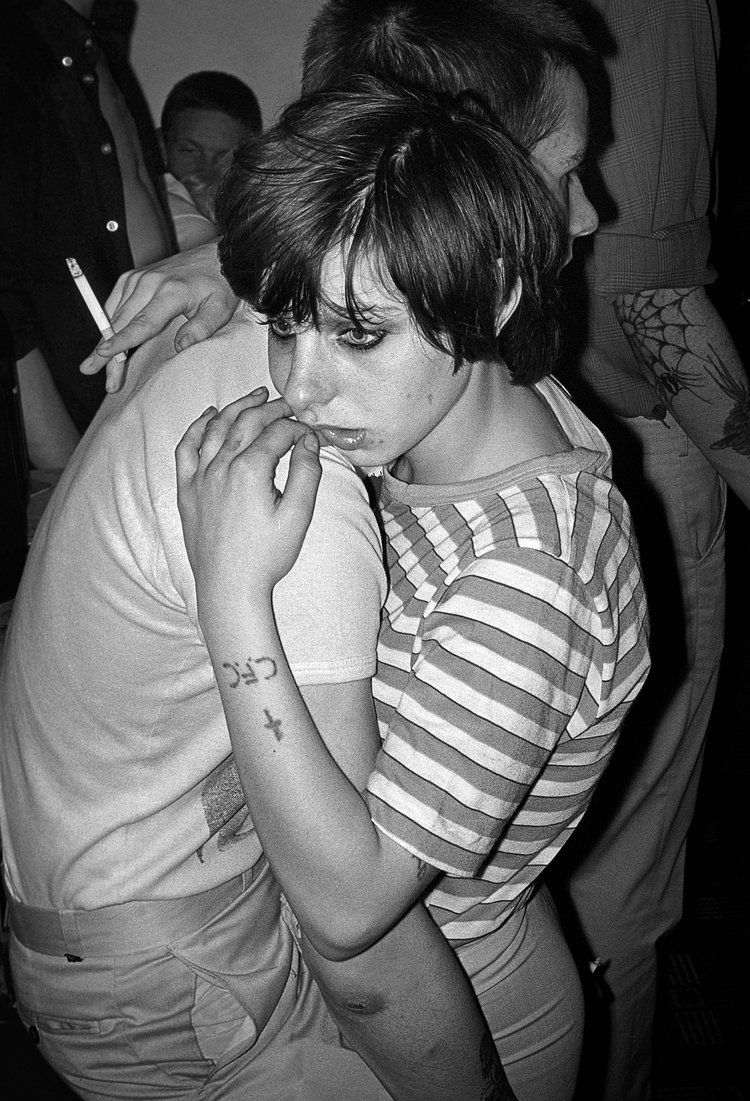

Images (Top to Bottom): Babs, Soho, 1987. C-Type. 16 x 20”. Edition of 10; Nick Cave, 1984. C-Type, 20 x 24”. Edition of 15; Tuinol Barry, Kings Road, 1983. Silver Bromide, 16 x 20". Edition of 10; At Heaven, London, 1981 . Silver Bromide, 16 x 20". Edition 5; Jarvis Cocker photographed for NME, Carburton Street, London. C-Type, 20 x 24”. Edition of 10; Stoke Newington, 1980, Silver Bromide, 20 x 24. Edition of 10