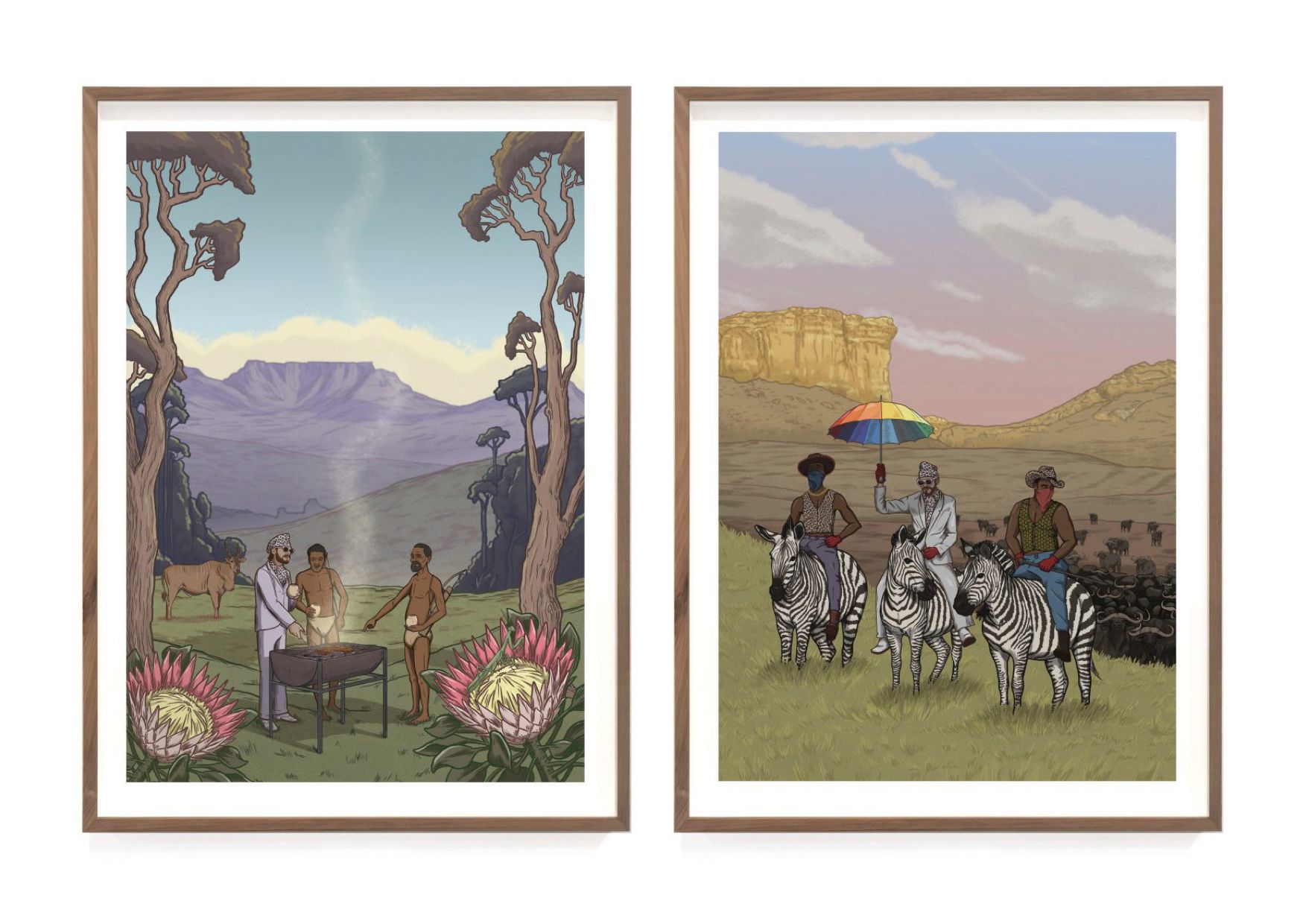

The South African artist, musician and performer Xander Ferreira has a penchant for wryly deconstructing post-colonial narrative tropes and is better known to most by the nomenclature of his alter ego Gazelle – the chart-topping ironic musician whose afro-futurist style borrows liberally from the iconography of dictators. His latest playful foray into the arena of cultural propaganda comes in the form of Postcards From Paradise, a collaboration with the illustrator Llewellyn van Eeden that blends mythology and history in various scenes in which his somewhat iconic alter ego is depicted sashaying across South Africa’s nine provinces. Postcards From Paradise was chiefly inspired by the famous Pierneef ‘Station Panels’ on display at the Rupert Museum in Stellenbosch – masterful landscapes from the 1950s that were later co-opted by nationalist elements in South African society during Apartheid. This nationalistic act of cultural appropriation plays into Ferreira’s notion that history is always ripe for manipulation, and inspired him to create a post-modern magical realist depiction of each province, and, if you like, steal them back from the negative connotations that they have become associated with. Here, the unique creative talks to Culture Collective about the power of repetitive symbolism, rewriting complex histories and finding beauty in unusual places.

What drives you and what interests you about satire?

With satire you can appreciate the beautiful elements of something dark and disempower it, or turn something that is harmful into something constructive, and I think that that is really at the core of my life and everything that I do. Within propaganda, branding or religion, or whatever it might be, it's never about what is the truth or what is good, it is just about repetition – you just take an icon and repeat it multiple times, over and over and over until it’s embedded in the mass psyche. I’ve always executed these steps in my art and performance because I am absolutely fascinated by how people convince others to believe in something simply by creating an icon. It never helps to just kind of destroy history because then you're destroying the truth, but you can look at history and find ways to disempower certain things, or break cycles. In creating Gazelle, I studied dictatorships and power because I want to play with all of that. It feels like the best thing I can employ to take on something serious – there's purpose and beauty in that for me. I find beauty in a lot of weird things.

Do you create from a political standpoint?

I just create what comes through me. I mean, I definitely believe in movements, and I appreciate them, but for me creating is just something that comes to me through ideas. And it's up to me to either let those ideas pass through and allow someone else to manifest them, or to manifest them myself. I don't believe we own ideas, and things like that at all. I believe people are just conduits for multiple ideas that come from a collective consciousness. In my work, I always go back to anthropology and history because that to me shows the clearest truth. It's very difficult to judge the moment you are in right now because your perception is always very skewed in the present – you can almost only look back at something to actually see what it was or what it meant. If you were in the swinging sixties in London, for example, you would not have known it was the swinging sixties, you were just there.

What is going on in the Postcards From Paradise series?

Each image in the series depicts a province of South Africa, and the inspiration came from the fact that the South African government today has never really commissioned a contemporary artist to create imagery based upon all the provinces. Historically people in power always commissioned art that captured their era, or reflected their truth – that's how we write history, by creating culture within specific moments of history to reflect a moment in time, whether it's art, architecture or literature. And that representation is what becomes a notch in history. In Postcards From Paradise I was inspired the Johannesburg station panels that were painted in the 50s, because they're so beautiful to me. I saw them for the first time a few years ago in Stellenbosch, and I was like, wow, these are such beautiful masterpieces. Then I started reading about them, and mixed emotions came up because some people feel they were used in nationalist propaganda – and yes, they were much later co-opted to become nationalist propaganda in the 1970s, but they are still beautiful landscapes. You need to look at the beauty in something to disempower the other meanings that people have placed onto it over time.

Why is that process of disempowering so important to you?

It’s important to disenfranchise the negative energy – it’s like that thing in Buddhism about turning poison into medicine. So, I was like, okay, I'm going to commission myself to do pieces on all the provinces, and I'm going to choose one place of natural beauty in each province and fuse the history and mythology of the place to create something that doesn't exist. Because what I want to do is talk about truth, right? I want to talk about how history is actually just told by manifestations of culture. If you think about any period in history then it was always the photograph or the book, or the painting that communicated the culture. So, I was like, okay, I'm going to create something that plays with that to show that history or mythology can be altered and manipulated by anyone, depending on who's telling the story. I set off on this goal to create one piece in every province where I could kind of re-engineer myself into the history to write a kind of new mythology and make something beautiful, but also pose many questions within the image by fusing many meanings together.

Can you elucidate a little more on this notion of fusion…

Well, for instance the idea I wanted to explore in the Northern Cape was to bring in the classic blue woman from Vladimir Tretchikoff because for me she very much evokes part of my childhood, because when I was growing up in South Africa in the 70s under apartheid practically every white African house had a blue Asian women on the wall. I try and look for meaning in all these things. and I wanted to explore why everyone found that beautiful. I loved the idea of bringing the blue woman, which is agnostic to race, but yet identifies culture through the Asian dress into this sprawling and beautiful landscape of different flowers. I'm not talking about diversity in a political sense. I'm talking more about just how the world actually exists in terms of its differences and juxtapositions all making up one thing. There’s also the piece that references Napoleon Crossing the Alps by Jacques-Louis David because for me in terms of art history, it is one of the first propaganda pieces. The painting was repeated and sent to royal houses in different parts of Europe as a propaganda piece. Because when you are a king or an emperor or whatever you are, what do you do? You make portraits of yourself and sculptures of yourself, because that's how you become an icon. It interests me to be playful with that. I just love bringing together all these different elements and creating images that you can dig a little deeper into. If something is beautiful to me or important to me, or touches me in some way, then I always feel like I have to share it, because maybe if it's beautiful to me, it can be beautiful or important to someone else.