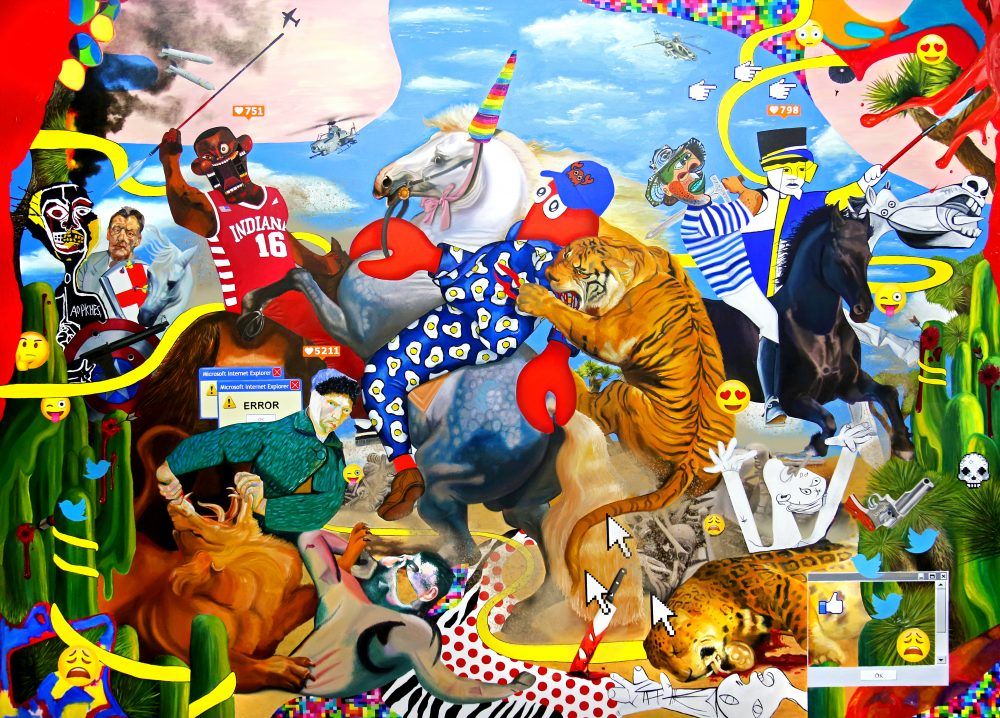

The British multi-disciplinary contemporary artist Phillip Colbert has always cut a unique figure at the heart of the alternative scene in London, being shot at myriad gatherings of the hip, beautiful and damned over the last two decades adorned in his own wearable art. In fact, the designer-turned-artist once famously described as “The Godson of Andy Warhol” by Vogue has long been recognised by the denizens of East London as one of its most flamboyant icons – one who has exploded on to the global art scene with an increasingly gargantuan project with which his name, and indeed identity, has become utterly synonymous. In the last few years, the Warhol Factory-esque industrial creative studios he runs in Shoreditch and Lewes have been creating a veritable smorgasbord of neo-pop surrealist fantasy worlds featuring the comic-heroic figure of his trademark bright red lobster – traversing art history, building interactive cities in the metaverse and appropriating almost every imaginable pop culture reference along the way. This cartoon-like character is forwarded as the alter ego of the artist, who employs his invertebrate avatar as a tool via which to intravenously pump himself into a heavily layered hyper-saturated pop world that pokes fun at the obsession with consumerism that so resolutely defines our era. The world this lobster inhabits is one that is utterly surreal and has no definable borders, existing in sculpture, across huge canvases, and most recently in Lobsteropolis City – the largest art world on Decentraland, where Colbert recently sold-out of his 7777 lobster portrait NFTs, which provided each owner with a key to the city, and led to 7777 real-life lobsters being released into the wild. Culture Collective visited the artist in his frenetically busy studio to discuss the conceptual genesis of the lobster universe, and find out why a background in academic philosophy underpins everything he creates.

Where did your journey as an artist begin?

I studied philosophy as a kid and it really switched on my brain. It’s just that power of perspective thing that it gives you – the realisation that purely by changing the way you look at something, the situation you are in changes. My identity completely shifted when I was reading philosophy, because that was when I first realised identity is malleable – you can change it, you can create it. There is something so institutional about schools – the fact that education is a conveyor belt which packages people up to certain positions, and philosophy can break that machinery. It allows you to un-peel a little bit of that and think about things much more objectively, leaving the particularity of your position. I wanted to enact philosophy in life somehow, and I was always drawn to the freedom of expression in bold art that challenges boundaries and pushes ideas of what art can be, art that can potentially become kind of a language.

What do you mean by art becoming a language in terms of the lobsters?

Well, when I say language, I mean art that becomes part of a discussion on what art can be. I was always inspired Warhol, who was applying a specific philosophy to his own every day life, and to what art could actually become, and what consumerism could actually become. Before I called myself an artist, I was a designer and in my fashion I was making what I called wearable art, and I was kind of trying to exist as this hybrid idea within the 21st century language of brand and product. My own philosophy in doing all of that was humour based, or based on trying to sort of satirise hierarchies and petty conservatism, or the absurdity of social constructs. I always connected to arts that I felt had humour, and that primary radiance of raw creativity and spirit. So, the symbol of the lobster with its surreal connotations worked completely for my philosophy, and my language. Even before the paintings, I was already heavily associated with lobster, because it was already my little cartoon signature in my fashion, and I was always using red in my signature colour.

What does the lobster as a symbol represent to you?

Well, in my mind the lobster is kind of the protagonist of surrealism. I've also always had this idea of the lobster as a kind of tragic figure, because, obviously, the red lobster is a dead lobster – he's already gone; he’s a mortality symbol. In addition to that, my lobster persona has got no mouth, so he’s silenced, and I always connected to Charlie Chaplain's figure as a sort of comic device. The lobster also always connects me to this image I've always had in my head of a medieval night – again, like a tragic figure, almost so ridiculously laden with heavy armour that he can’t move. So, when I decided to concentrate on making art and came to my paintings, it was just a matter of transforming and personifying this idea of the lobster, and then that immediately created the narrative dimension. I always say that when I became an artist, I became a lobster. And the beauty of having that persona is that it allows you to make a language, and gives you the freedom to tell stories in the dimension you have created.

And your lobsters are travelling through a multi-dimensional history?

Yeah. I guess so. I mean, the more I think philosophically on a metaphysical level, the more I believe in the idea of time and history being something that exists all at once – this idea that we are always living in living in the ruins of the past, and that all time is layered. I do believe that everything does exist at once, in a way –having all these ideas of history existing within my own perception of reality. So, I have always thought it was great to be able to create images to represent these metaphysical journeys, or ideas about the layering of time. The lobster is an interesting symbol in that regard, because I tend to think of the lobster a being bit like the closest thing we have on earth to an alien. I mean, it’s been living at the bottom of the sea for millions of years. I've actually started collecting lobster fossils, some of which are a hundred million years old.

What made you create Lobsteropolis City in the metaverse?

Well, I have always been very inspired by multi-disciplinary figures, like Diaghilev and Malcolm McLaren, and the phenomenon of pushing the boundaries of experience. I really wanted to create a world, and I had already created Lobster Land as a virtual reality experience back in 2018. So, before creating Lobsteropolis in Decentraland, I was already working on these kind of things, because I thought it was very important to present and show the elasticity of pushing these new mediums. I wanted to be showing that art could be elastic and more democratic, and I think that an important part of what makes good art is being true to that spirit of elasticity, you know? Not being easily pigeonholed; not being stuck. Making my work more democratic let's say, or widening the reach of it just feels important, and there is a sense of freedom you get in creating an interactive world.

Find out more at www.philipcolbert.com

Credits (Top to bottom): Lobstar from The Lobstars NFT Collection by Phillip Colbert; Lobster Land installation, Shanghai Modern Art Museum; London by Phillip Colbert; Desert Hunt by Phillip Colbert; Joshua Tree by Phillip Colbert