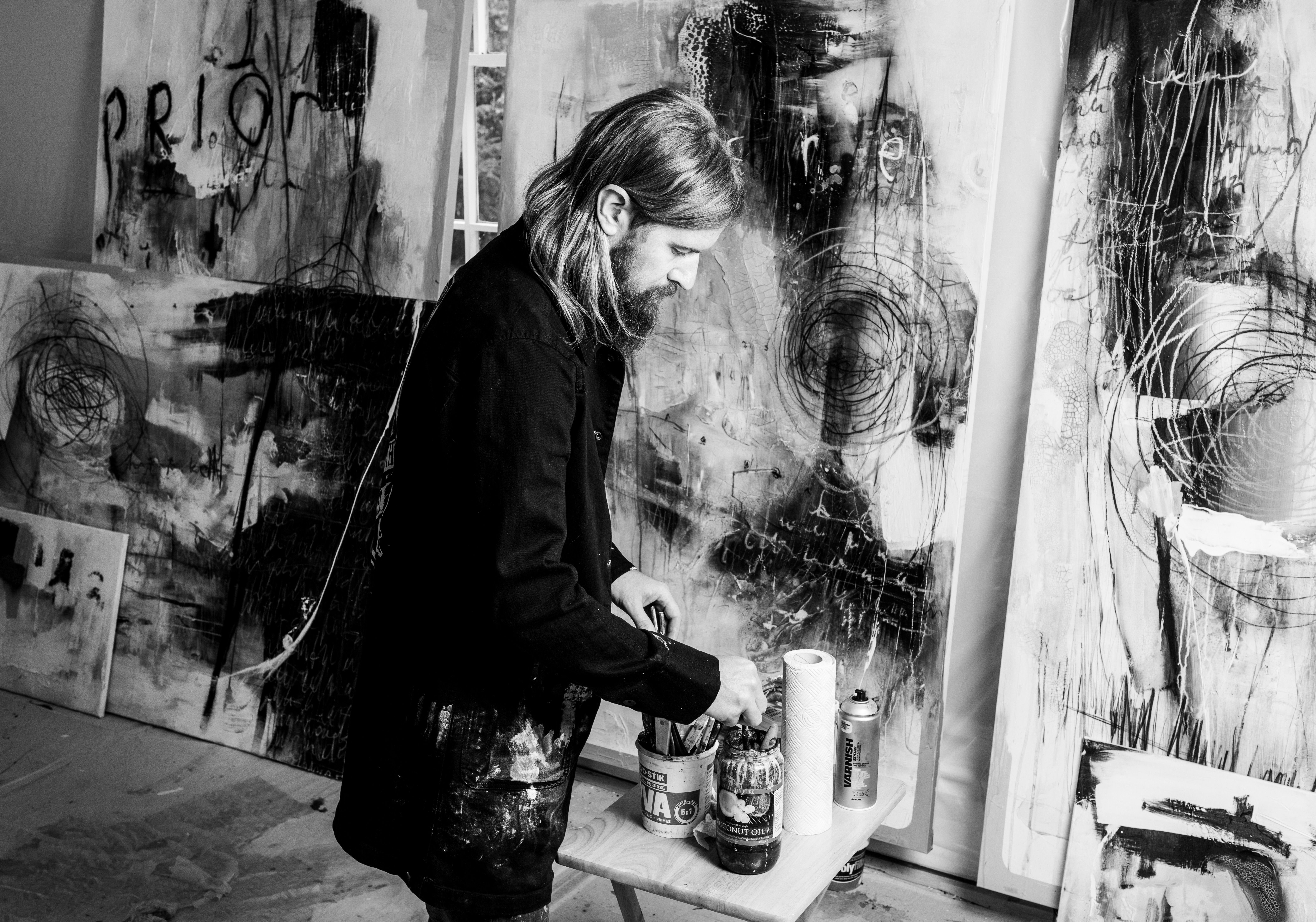

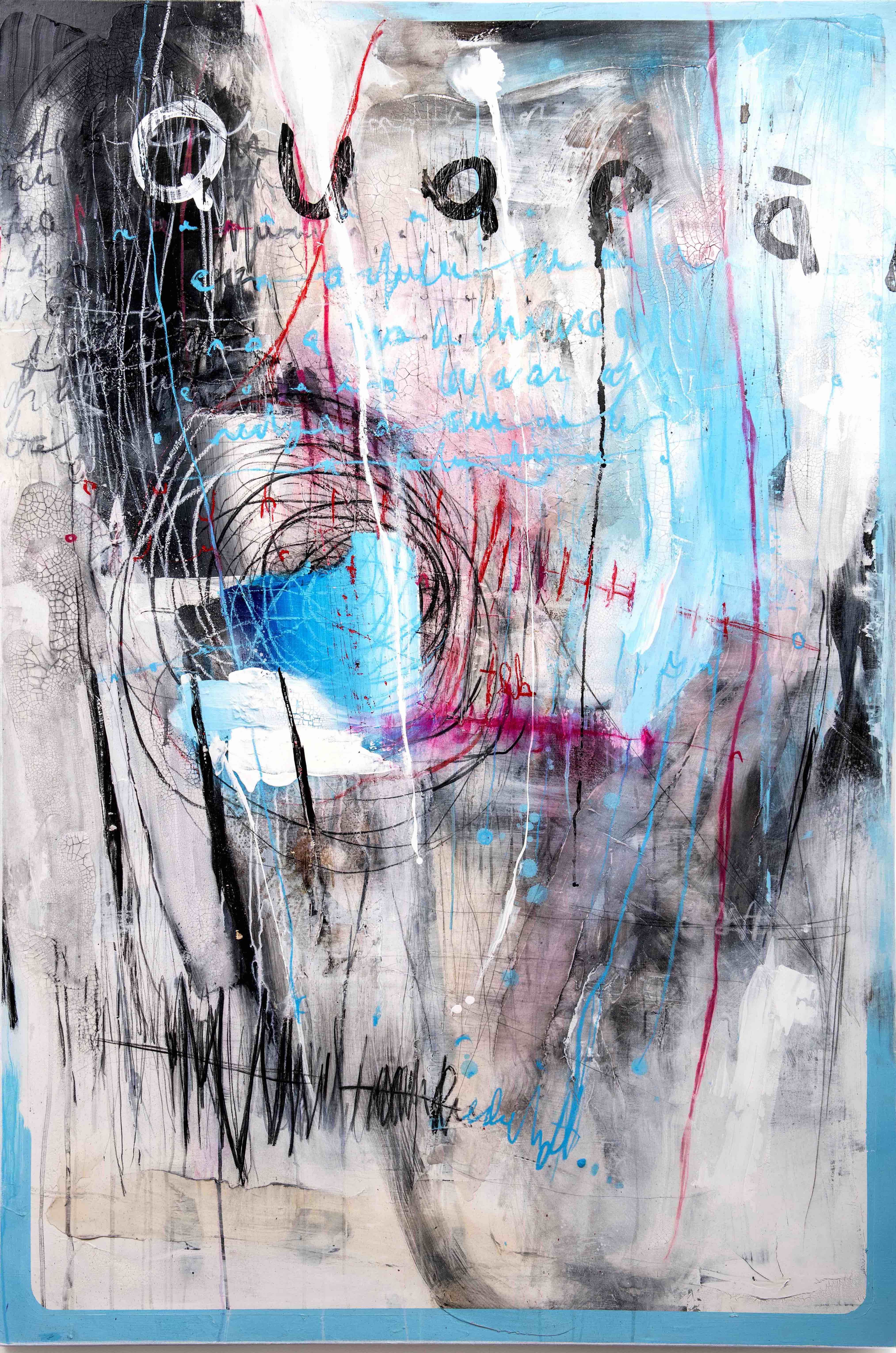

The Yorkshire-born artist Schoph is synonymous with some of the most collected signature lines in the skate and snowboarding scene, and over the last decade he has expanded his practice to enter the arena of fine art – working across various mediums, such as abstraction, stained glass and resin. Polymorphous in his talents and citing the likes of Cy Twombly and Pollock as key influences, he blends time-honoured action painting techniques with a graphic design aesthetic to create both deconstructed portraiture and fantastical scenes that now feature in major collections across the globe. His recent series The Quarantine Paintings are perhaps his most celebrated works to date, displaying Basquiat-esque verve and exploring the tortuous emotional landscape experienced during the pandemic and various lockdowns – providing a unique window into the darkness and collective trauma of that period. Over the last decade, he has exhibited widely in the United States and, perhaps unsurprisingly given his notoriety in the skate culture, now divides his time between the wilds of Yorkshire and Los Angeles – continuing to contribute artwork and graphics to major global brands, such as Vans, Volcom and Lib Tech. As if that was not enough to be getting on with, the tireless creative has also recently undertaken various major commissions, such as the mural work he created for Michelin-starred restaurant The Man Behind the Curtain, which reignited his relationship with his native Northern England. Here, the artist tells us why it's important to stick to your guns to realise your dreams, and explains why a working-class hero is something to be.

Can you recall what first drew you to drawing as a child?

I had always drawn and I had always sketched, and that visual side really came first for me in terms of communication – I didn’t actually speak until I was about three years old, and my parents thought I might be mute, and unable to speak. All that they would ever see me do as a child was draw. When I looked into that as an adult, I found out that there are many people who didn’t speak until much later, but back then it was just seen as odd – at that time, nobody talked about dyslexia, especially where I was from. I grew up in a very working class environment and went to school in an area where the expectation was to leave school and go straight into a trade, but, genuinely, the only thing I was ever any good at at school was art. I do remember one defining moment at school that probably convinced me to follow the path of the artist. We had a still-life class with this very extravagantly dressed teacher, and we were supposed to be drawing a fruit bowl. I thought, well, I don’t want to do that, so I started drawing my own picture – it was pretty surreal, to be fair, depicting these Friesian Cow-like rabbits being fished by some fishermen that were sitting in the clouds. Anyway, the teacher grabbed it, screwed it up, threw it in the bin, and told me I would never be an artist, or take her art class again. I salvaged it, and still have it today. I do think that moment sparked a little flame in me – that thing where you want to prove someone wrong.

It sounds like the notion of making a living from art would be a totally alien concept in that environment …

Exactly. I didn’t know you could be an artist, and I came out of school with nothing. At 15 years old I went to work in a butcher’s shop, which obviously had nothing to do with art. I had no interest in plucking pheasants and skinning rabbits all day, but I was stoked to be making some money – the only thing I had done at that point was a paper round. The job gave me the time and the money to carry on painting and drawing, and it was also when I discovered skate culture and skate graphics. It was kind of an epiphany to find out that skateboarders made art. The discovery of skate culture opened up everything for me – it took me away from all of the stuff that had happened at school. It introduced me to a much more expansive world, and, down the line, it’s what got me into snowboarding. From the butcher’s shop, I worked my way up to becoming a head chef and running my own kitchen, and all through that time I was also becoming more and more immersed in the culture of snowboarding, and still drawing and sketching constantly. I was balancing so much in terms of work, but the draw to the Alps and snowboarding was strong, and I was lucky that I was good enough that I could pursue snowboarding professionally. It is strange to look back, because everything that was inspiring me was the polar opposite to what I had grown up with in Yorkshire.

What was the turning point when you realised your art could be a full-time profession?

It wasn’t until I had been snowboarding for a good few years professionally, and being sponsored by different brands, like Vans, who I now work with on signature lines. In my early 30s, I got a lot of injuries from the sport, and it was really taking its toll on me physically. I think timing is everything, and, at a certain point, I just felt it was time to throw in the towel and to get out before something really serious happened. I didn’t really know what I was going to do, and was taking all sort of jobs, but just missing the mountains so much – I felt a little lost, to be honest. Then out of nowhere, Lib Tech called me up and said, look, we have a fifteen-year relationship, how about flipping that and working with us an artist, we’ll put your art on boards and create signature lines – so, it grew really organically from there and I began working more brands like Volcon and Vans in the context of being an artist. I had always liked to think that my artwork would speak for itself one day, and I suppose that is exactly what happened. I remember seeing my first graphic on a snowboard at the SIA trade show and it just blew my head – it was something my fourteen-year-old self never could have dared to imagine. I had always thought in the back of my head that it was what I wanted, and I guess I had always been working towards that moment.

How did the graphic work you became known for evolve into the more abstract canvases that you are now creating?

Well, it comes from two things. One, I never understand artists who talk about getting stuck or procrastinating. I never stop working, actually. I never procrastinate, because to me being able to be creative for a living and be fortunate enough to do what you want to do is such a huge privilege. And I think, because of the way I was brought up, I do believe that to progress you have to work every day at your goal, you have to keep going. I don’t see how someone can procrastinate on something that they are not being forced to do. The second thing is that so many of the artists I know get themselves pigeonholed by others as only being able to produce one thing, or feel that if they have an idea that wouldn’t be achievable in the way that they work formally that there is not way for them to do it, and pigeonhole themselves. But if I get an idea that doesn’t work in the graphic form I use then I will simply explore another style – that is how I got into producing work in stained glass, for example, as well as the abstract, mixed media, resin and acrylic work that I do. And I will know when I am working in the right mode for the idea because it just flows really naturally, and once I am in that flow I will just keep going. I’m not scared to try new things and will percolate ideas until the medium presents itself, and I like to switch between things. It was really discovering Cy Twombly that spurred my evolution into abstraction, and into pulling lyrics, and so on, into my work, and RedHouse have always really supported me in that. Having said that, I try to do my best to allow the abstract work to simply flow in a certain way, and not to overthink it, or allow it to feel too influenced from the outside, in any sense. I try not to compromise on anything I do. I think maybe that comes back to punk and the skate culture. It’s best not to overthink anything. I believe the most important thing in life is to be your authentic self.

Schoph is represented by RedHouse Gallery. You can find out more about the artist here.