The self-taught African-American artist Hampton Boyer’s London debut at OMNI effortlessly marries a bright, bold faux-naive pop aesthetic with social conscience, cartoon violence and meditative contemplation. Haling from Hampton Roads, Virginia, Boyer extrapolates broad societal themes in his work from his personal experience of growing up in a heavily policed suburb of a US state historically synonymous with the racial apartheid of the Jim Crow movement and a brutal legacy of oppression. His work in Memory Dances disarms the way in which this spectre from the past still permeates contemporary society via an armoury of humour that owes no small debt to skate culture, and he brilliantly juxtaposes his vivid scenes of police brutality and drop-kicked Klansmen with thoughtful geometric still life works that communicate quiet spiritual introspection. In this rare interview with Culture Collective, the artist tells us why creativity is essential for survival, shares his thoughts on profound loss, and explains why overcoming adversity is the only path to joy.

Where do you think your creative drive as painter comes from?

I was kind of surrounded by sci-fi and animation as a kid. I watched a lot of cartoons, and would always doodle and create stories, and in the evening my mom would often let me watch Star Trek or Xena Warrior Princess with her. But it was skateboarding that really kind of enriched all of that in my early teenage years, and crystallized my interest in being a painter – skate culture opened my eyes, and I could kind of see this connection in there to the art world. That link had not yet been validated, so it was still kind of fun, and there were no rules, really. I had always been creative, but skateboarding graphics really enhanced expression for me – you know, someone might be illustrating how they are in an abusive home, or are facing these very real things, but it’s always depicted with this silver lining of humour. Seeing that in skate graphics helped me to examine things that I was facing, and use art as a vehicle.In Memory Dances, The Eternal Battle is a work that is reminiscent of early skate graphics, which, for me, always contained this sense of speaking your truth, or speaking about society. The skate culture gave my work a good head start in the beginning, helping me to utilize that voice and outsider perspective – still having form and composition, and all the things that fine art has, but going about it in a way that's more passionate.

It sounds deeply personal …

I have a bunch of pain with deep connotations, and how I illustrate that always comes through drawing, or just meditating through whether I want to represent it figuratively, or in a more abstract way. I sometimes wish I created work that was more kind of surface, but if I did, I don’t think I would have this same gift to be able to talk about these things. Where I'm originally from is a heavily policed city, and on every single corner you see a cop car. The system creates so many rules and infractions that, if a cop is bored enough, he could turn anything into something. I think that environment is partly where my creativity stems from. I'm not going to take away from anyone's experience of wanting to be a police officer, or anything like that, but it’s a flawed and predatory system.

These are heavy subjects but you juxtapose them with this faux-naive kind of pop aesthetic – what is that juxtaposition about for you?

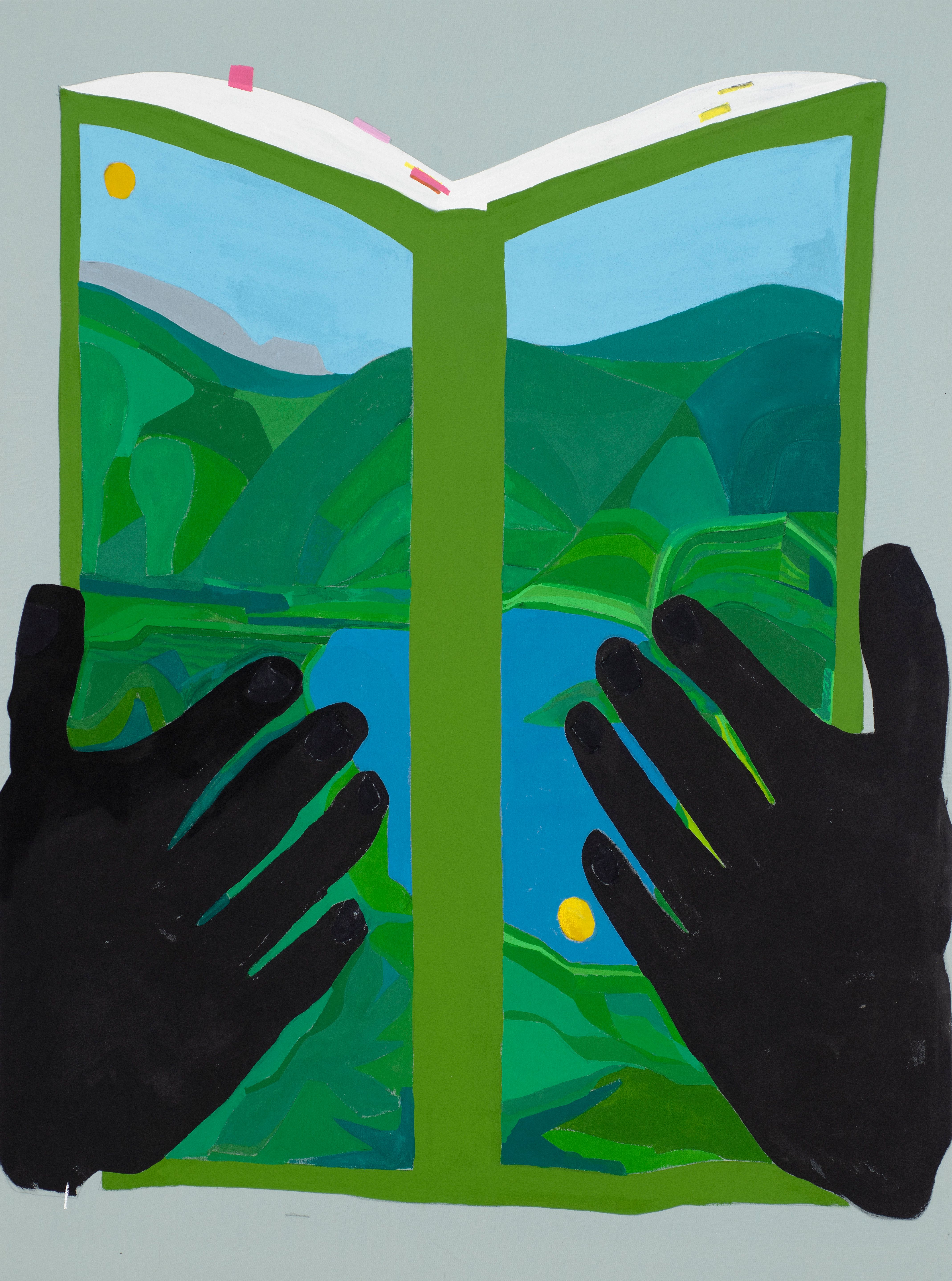

I think it's a way for me to bring the viewer into these things – I think with any artwork, the viewer is always invited in by something, whether that is the colour, shape or form. And I always feel like I want to bring the viewer in to spark interest and contemplation. If I made it so that the paintings felt like how it might be when someone at a dinner party brings up a political conversation, and you're like, oh, I don't want to get into that, it wouldn’t be the same. If it's bright and has this arresting feeling, or invitation, then you just deliver the message, and people have a little bit more time to contemplate it. That’s where I kind of get that from, plus it kind of feels good sometimes to make something bright and colourful even though it has a deeper meaning. With the works in Memory Dances I want the viewer to see that I am still creating from this place of fighting oppression, but that I'm also maturing to find my own place in the art world, and also that I am not allowing the challenges of life to take away my joy. I am on the search for what feels good.

What do you fundamentally think the role of the artist is in society?

I think that the artist has a massive purpose in life that is way outside of the rat race and, you know, everyone trying to up their career through social media, or whatever. I think that the ability to be able to conceive an idea or to be able to write something or bring an image into form is so important. And I'm thankful for this gift of communication, because there have been times where I thought I lost it due to depression, or what I might have been going through at that point in time. And personally, art has helped me in a lot of ways. I lost my mother in the last few years, and I've made bodies of work in dedication to her and to the process of grieving and acceptance. I also lost my brother when I held my first museum show. I think the spirituality creeps into my work because of those kinds of losses, and just because of the abundance of things that happen in my life. There have been a lot of times in my life where, like most people, I felt like, I don't know how I'm going to make it through, but I make it through. It means a lot for me to create another day, because as an artist, my creative flow state is what keeps me surviving. And I just try to process all these things as they happen to me because I know now that life is short, and it continues to teach me lessons on how to treat people right, or how to forgive, or how to move past things or aren't in my control. These kinds of things change you. And I see so much beauty in life now that I am compelled to create from that standpoint.

Hampton Boyer exhibits at OMNI, London until February 25th

Find out more here

Images (top to bottom):