There are currently a staggering 108.4 million people displaced on Planet Earth, with an estimated 43.3 million being innocent children. Let that statistic sink in for a moment. Tragically those numbers do not represent the zenith of human folly and cruelty - rather they continues to rise year upon year. It has been no less than thirty such years since the now infamous charity exhibition ‘Little Pieces From Big Stars’ – the brainchild of David Bowie and Brian Eno that was presented by Flowers Gallery in association with War Child UK to raise awareness of the scourge of war on childhood. During Frieze week the gallery have chosen to mark the occasion with an autumn fundraiser that couldn't be more timely. Presented by War Child UK and created and curated by Intersectional Feminist Art Collective In Fems the exhibition Lost Girls brings together an impressive panoply of global artists to respond to the profound challenges faced by girls affected by war. The current InFems Artist-in-Residence and guest co-curator Nadia Duvall is herself a former child refugee who describes herself as 'a bug on a permanent journey. A lost girl with suitcases full of nothing, but heir to a full voice.' In this interview with Culture Collective she takes us on a journey into her art practice, shares memories of a troubled childhood and tells us why we can always hope for a brighter future.

Do you believe all art to be political?

Yes, for me, all art is political. Even if we decide to isolate ourselves on a mountain, it can still be considered a political act. As Jacques Derrida said, 'everything is text, everything is context'. It's impossible to distance ourselves from the information that reverberates around us. An artist can, of course, choose to be an activist or not, because being political and being an activist are different things. I consider myself an activist, and the art I produce is intentionally political, even if it's not immediately interpretable. I use poetry in my work because I think it's too much to stick only to political ‘things’ – we are so much more than mere political animals. What, for example, do we do with the epigenetic memories that run through our blood and genetic code? These are memories that we don't even know we have, and the subject of such memories play a big role in my art.

Do you think you were always destined to become an artist?

Well, it seems that certain destinies are more or less inevitable, and mine is probably one of them. I believe we are all the context in which we are born and grow up – it is written on our skin, on our identity – and all of the earliest memories I have are accompanied by both trauma and coloured pencils. Even when I barely spoke because I was so completely closed off from myself, drawings became my tool for communication. The very earliest memories I have take me back to Algeria, where my mother lived with my father. It's a long story, but, in short, my mother grew up in a Catholic family in Portugal, which was extremely conservative. When she was 16 years old, she ran away to Spain, where I was born, and met my Algerian Muslim father. They decided to go to Algeria where, unbeknownst to them, a marriage had already been arranged for my father. He couldn't escape the intense Islamic religiosity and ended up getting married, keeping my mother as his mistress. In this context, my sister was born. Shortly afterwards, my father, who was known in Algeria as The Man With Fifty Faces, was arrested and imprisoned for criminality – leaving my mother alone and unmarried in a fundamentalist country.

It was at this stage that you left the country as a refugee?

Yes, my mother had to flee Algeria. She tried once, and was caught. The second time, she had to choose to abandon her youngest daughter and flee with me. I can still remember a lot about that journey – the hunger, the suitcases, going from house to house, and my mother being unable to bear the pain she was in because of the HIV/Aids that would kill her when I was just nine years old. Before she died, she managed to get me back across the border to Portugal where I was adopted by my her family, who were also extremely affected by my mother's trauma – not only projecting their pain onto me, but also being extremely inflexible in my own upbringing. My adolescence was extremely difficult, and I can say that art, in those phases of my life, became an escape mechanism.

It seems religion has had a huge role in shaping you as an artist …

Religion is always present in our lives, even when we say it's not. Religion has totally shaped society, and I'm afraid it's impossible to distance ourselves from it, whatever it may be. It is always present, even if it appears to be invisible. That's why I can consider myself completely religious, having drunk from multiple religions since birth – Islamic, Christian and, finally, Buddhist. I'm religious to the core, even if I say I'm not. The construction of religion is a construction of religiosity in each of us, which arises from context. Deconstructing religion is only possible if we talk and debate about it openly for generations and generations, which I don't believe is possible because history is cyclical, as are humanity's mistakes. I don't consider religion to be a mistake, but rather a legitimate need that primitive man found in order to realise his place in the world. And just like primitive man, many of us still need a certain meaning in life, because it fills us with a certain happiness, a certain hope. In such a dark world, is it so bad to seek a certain religiosity? We can be religious without having a specific religion. I think art also comes from that abstract space – from spirituality and religion without religion.

What would you say essentially drives you as an artist?

The choice to be an artist, despite being an act of courage, is also devastating: society devours everything from the artist and always wins, while the artist generally remains in precarious situations and in a constant struggle against the very perversity of the system they have chosen. In other words, the artist has two battlefronts: on the one hand, the fight against society's systems, inhumanities and a whole paraphernalia of political, social and religious issues. On the other hand, they are faced with the battle of the art world, which is petty and elitist. When I was invited to be part of the Lost Girls project organised by War Child, Flowers Gallery and Infems, I actually realised how relevant what I was already doing as an artist was. Sometimes an artist needs certain motivational engines to remind us who we are and what we want. This project was one of those drivers, as it made me realise that I was on the right path as an artist and that everything I was producing was in fact a manifesto and a reflection of our society. I don't believe it's possible to change society with art, but I do believe it's possible to create frictions in it to the point of creating ruptures – artists are war machines, and the work I'm presenting in this incredible project has that essence.

How would you describe your work and its chief concerns?

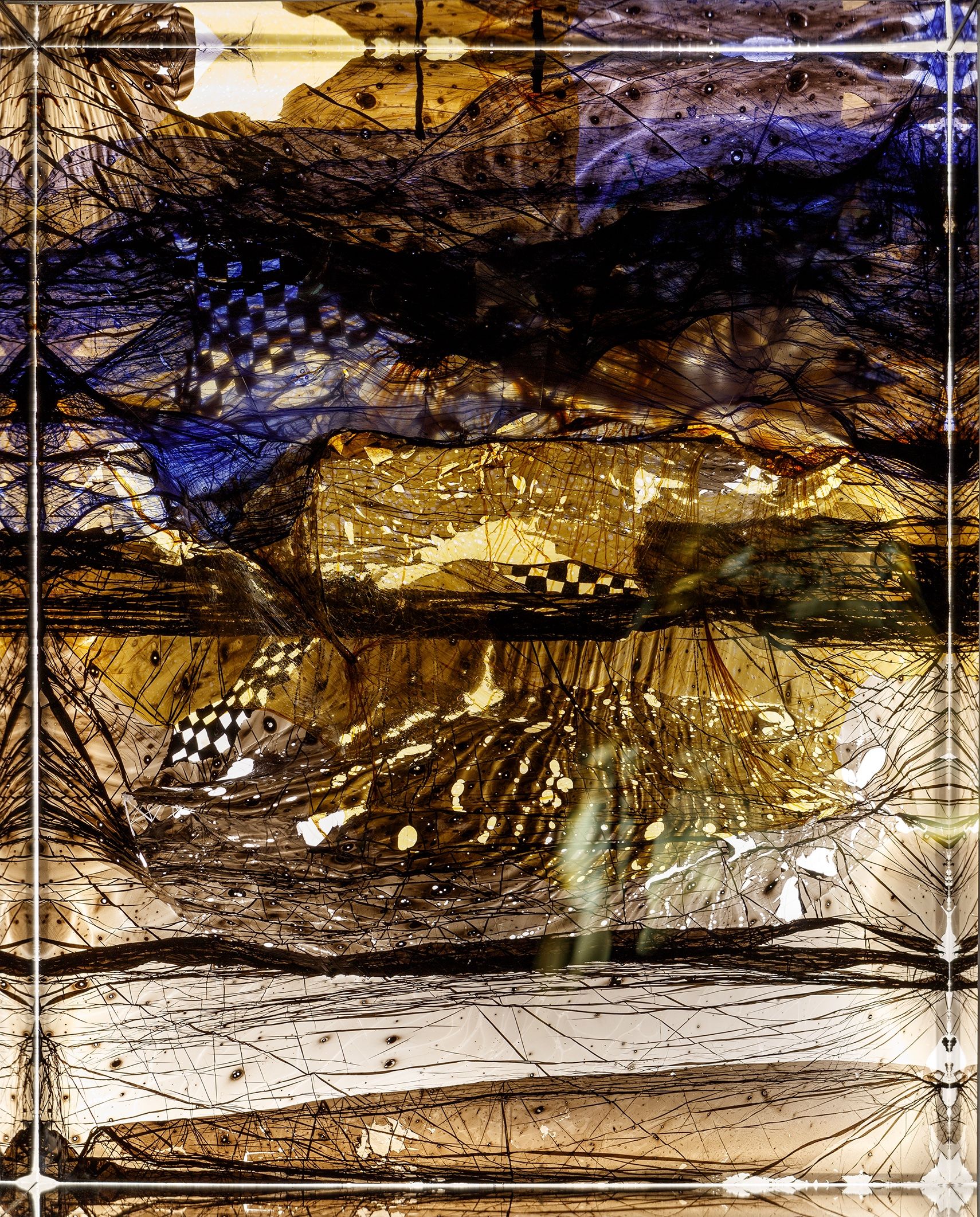

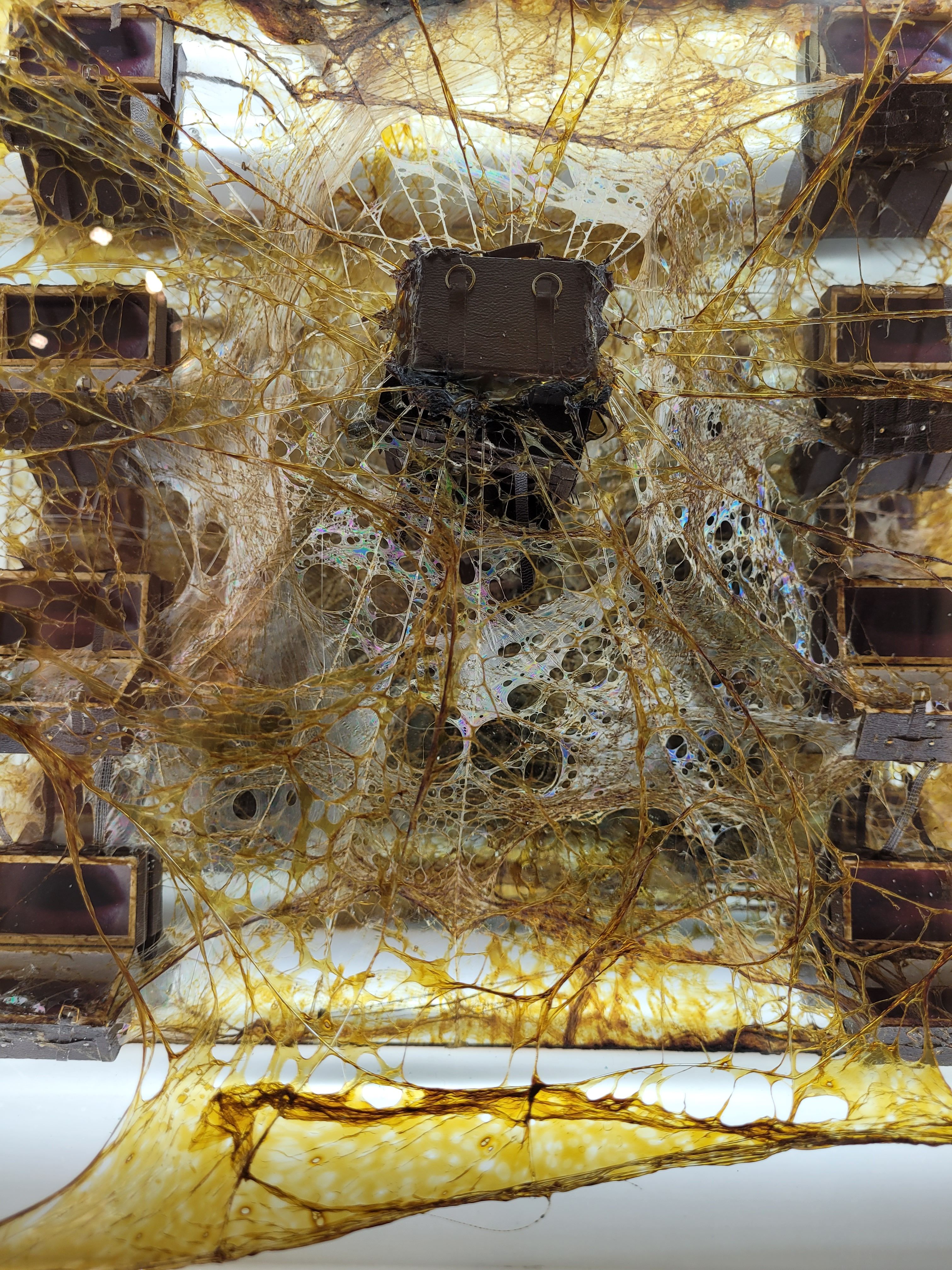

My work explores a concept of hybridity, which comes from two factors. The first, and perhaps the most important, is the heteronomy in my work. In other words, in my artistic process I have developed several different personalities, each with their own biography, and each one of these personalities does something different in the studio. However, these personalities also work as a collective and, in this sense, they can come together to work on a single piece. One personality writes, another draws, another is an alchemist, another is obsessed with miniatures and doll’s houses, another is a kind of insect, another is a sculptor, etcetera … As such, my artistic work reveals a potent hybridism where not only the mediums are always different, but also the techniques. The only thing that remains more or less recurrent in the work is my Ink Skin, and I have a pool in my studio where these 'skins' are made and developed. The interesting thing about heteronomy is that perhaps it comes from my father's influence, because as I said earlier, he was known as the Man With Fifty Faces. Another phenomenon in heteronomy, extensively studied in my doctoral thesis, is that not everything we see is always real. There is a certain fiction in the personas I create, and in what they say or do. They dwell in what I consider to be 'beyond physics', in other words, in 'pataphysics', and they work in a kind of convulsion, because not all of them are always active. I call them Epileptic Machines, and even this may have been because I suffered from epilepsy from childhood to adolescence. In my work and artistic process, nothing is by chance, everything has a reason.

Lost Girls is currently showing at Flowers Gallery and works by contributing artists are for sale via Artsy until October 26th. All proceeds support the essential humanitarian work done by War Child across the globe.