Stuart Semple is British artist whose longstanding trans-disciplinary practice has witnessed him earn some unusual accolades, such as UN ‘Happiness Hero’ for the ecstasy-pill inspired Happy Clouds he released into global skies following the economic meltdown of 2008. And it’s fair to say that positivity and social conscience is a consistent thread running through all of his work, which tends to spin wildly upon an axis of anxiety, consumerism, society and activism, whether manifested in sculpture, painting, site-specific installation, or art activations so unusual that they defy definition. While he is seen as one of the first artists to utilise the internet in his practice, his most recent addition to a long list of achievements is his very much non-virtual role in founding GIANT, the first Contemporary Art Museum in Bournemouth – a space conceived during the pandemic that has gone from strength-to strength, exhibiting globally revered artists, and transforming the cultural landscape of his home city. In a career spanning three decades, Semple has exhibited at numerous exhibitions, fairs and biennials, and at prestigious institutions, including The Barbican, ICA London, Frieze and Art Basel Miami, and he has created large-scale public projects for cities all over the world, including Denver, which he attempted to transform into a ‘Happy City’. He also became something of a household name after going head-to-head with Anish Kapoor in a very public spat about the liberation of art materials, when he re-created and made widely available the ‘blackest black’ Kapoor had bought from the US military. In this exclusive interview with Culture Collective, the artist warns us of the dangers of digital pseudo-connection, tells us why indulging in creativity is beneficial to mental health, and explains why people don’t need an intermediary when discussing trauma.

Where do you think your creative drive comes from?

I have thought about this a lot and I think it comes from when I was a really young child and I didn't know where I fitted in in the world. I was quite anxious, and sort of lonely, and even from being a tiny boy art was the thing that kind of made me feel better. And that's not just making it, it's looking at it as well. It was just really beneficial to me, and I realised that it had the potential to lead to a kind of happiness, at least for me. I believe art is powerful and useful, and should be used for things. I mean, I don't think art has to have a social purpose – I think it can just be pretty or moving, or confrontational, whatever it has to be. But one of the things it can do is have that purpose, and I think it's really powerful in that regard. Art can kind of go where a lot of other things can't go, and I'd like to think a lot of what I do is sort of rooted in that idea.

What do you hope to engender in your viewer? Do you hope to make an emotional impact when you make a piece of work?

Sometimes, but not always – some things are just aiming to start a debate or a dialogue, or point something out. I use humour a lot, which I think is quite a good way of disarming things and drawing people into something. I think what the arts provide is an outlet for emotion, or an outlet for communicating what you've been through. What you tend to find is when people start engaging in art, whatever the art is – it might be writing poetry, dancing, singing in a choir, painting, whatever – they open a little doorway to start letting things out, and that's beautiful. It can even help people with mental health issues to verbalize their experience, and when you start combining that with other things like, maybe a bit of exercise, changing a diet, meditation, or whatever – you start to see quite dramatic changes.

Talk to me about the Emotional Baggage Drop project, because that piece of work seemed to absolutely play in that arena …

Yeah. That was really interesting one. I proposed the idea of a radical art intervention across the whole of the city of Denver that was aimed at inciting mass happiness. I mean, we didn't quite pull that off, but I attempted it (laughs). One of the pieces was the Emotional Baggage Drop, which lived inside the central train station, and the idea of that piece was to create something a bit like a Catholic kind of confession box, where one stranger would come in contact with another stranger, and they'd look at each other through just a hole in the wall. Then one of them would ask the other one if they had any emotional baggage they wanted to release, and that person would tell them whatever it was. Then they would leave and another person would come in, so it was kind of a chain reaction. And the idea of that came out of the removal of a mediator in the experience – we always have a therapist, or we have a psychologist, or, in the case of Catholicism, a priest, but why can’t we as people just come together and share something emotional without any paraphernalia in between? Some really profound things happened. They actually had a whole mental health team on-hand, because it's America and everybody litigates all the time, but no one ever needed the mental health support team – no one needed an intermediary.

Do you think that kind of profound real-life connection is disappearing more and more – sometimes in the smartphone era it feels like people are increasingly becoming isolated units of consumption …

Absolutely. I mean, the smartphone is a transactional tool, and it's in your house, it's in your pocket, it's in your hand … Yeah, the problem with it is that it's just pseudo-connection. It's actually quite an antisocial activity, but one that cons you into feeling like you're connected. You feel like you're part of something, but you're really not – you're not in a room with people listening to the same music, wearing similar clothes, having a shared experience. It has the guise that it's empowering you to create something and put something out into the world. But it's not about that at all. It is just vying for our attention, and we actually are the product. People are also increasingly kind of happy in these digital bubbles now, and it's almost like they're not going to realise what they've lost till they don't have it any more, which is terrifying. It’s like this instant gratification device, and there’s just no depth to it at all – when you scratch the surface, you realise it is mostly just funny cat videos.

So much of the imagery we consume now comes primarily through these devices – where do you stand on that?

There are two sides to it. You can argue about accessibility, and how it's great that we can go on Google Images and see a Van Gogh painting whenever we like. And there is something really powerful about that, because when I grew up, I didn't have access to any of that information. And you can watch a documentary on pretty much anything now. I don't think that's wrong. I think that's brilliant and beautiful. But I felt even from when I was very young that the art we saw in books was nothing like seeing the real thing in real life. I'm obsessed with colour, and if you go and look at a real Van Gogh painting and then look at the same painting in a book, you're not looking at the same thing. It's a very, very poor version. So, I do believe that being in physical proximity to something that someone else has made in the real world is just unbeatable. There's nothing wrong with the smartphone, and there's nothing wrong with the Internet, but you should be spending a decent chunk of your time with real human beings looking at real things, and sharing a real experience.

Your work often has a social or political aspect, and is about challenging class hierarchies – where does that come from?

It's a bit of a cliché, but I grew up in a working class family with quite a lot of poverty around me. I started to see quite quickly that I didn't have the same opportunities that a lot of other people had. I used to go to art shows, when I was a teenager and be told off by the gallery for being improperly dressed, or just made to feel that I didn't really belong there. So, I started to see that sort of social inequality quite early on, and I think that inspired me to try and do something about that. I think it all came out of a really strong sense of inequality and the social backdrop of growing up in the 80s – all the strikes and, you know, my poor mum working three jobs and still not having enough food.

Do you think there are distinct parallels between the 80s and the way things are at the moment?

There's definitely similarities to the 80s, and the mid-90s, in a way, as well – when we sort of came out of conservative rule into the labour thing. We're at a very similar point – that sort of incendiary moment that kicked off the whole Brit art Brit pop thing. I think anyone with a brain can see that capitalism is kind of on its knees, but what we don't have is a viable alternative, so we are in this perpetual sort of palliative care for late-stage capitalism. But we've also got this other backdrop in the youth, and what is completely doing my head in is this kind of apathy that they seem to have. I mean, the idea that there's going be a law passed that means we can't protest – the kids should be up in arms, but they're … well I don’t know what they're doing, where are they?

Do you not have much hope in the younger generation?

Not in the generation that came just after the millennials – they tend to live their life like it's a protracted Twitter argument. I can't get my head around them at all. They’ve just had it so good, and they've been so protected in a way. I think they've been sort of mollycoddled by the world and treated very softly. They go to university and demand a first-class degree because they have to pay for it – they're the ultimate consumer. I do have faith in the next generation, though. When you see how switched on these kids who are 15 years old are, and how they really care about the world – particularly things like climate change – then they put my generation to shame, you know? That's the hope really. It's a burden for them too, but my money is on those kids.

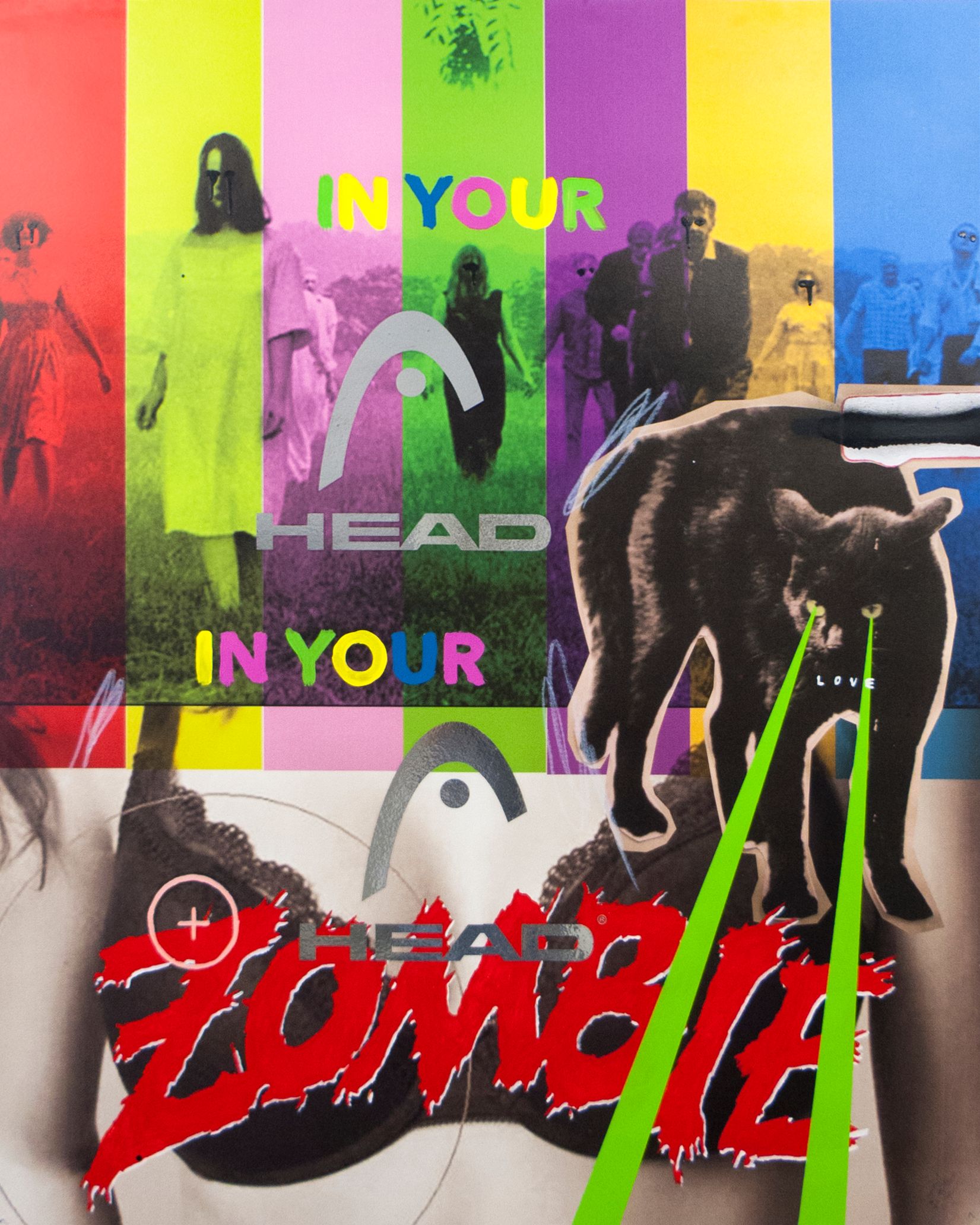

Images (top to bottom): Stuart Semple in his studio, portrait by Ed Hill; Black 3.0; Zombie Head, digital print; The Assassination of Kurt Cobain, acrylic on canvas; Happy Clouds, Denver; The Pinkest Pink