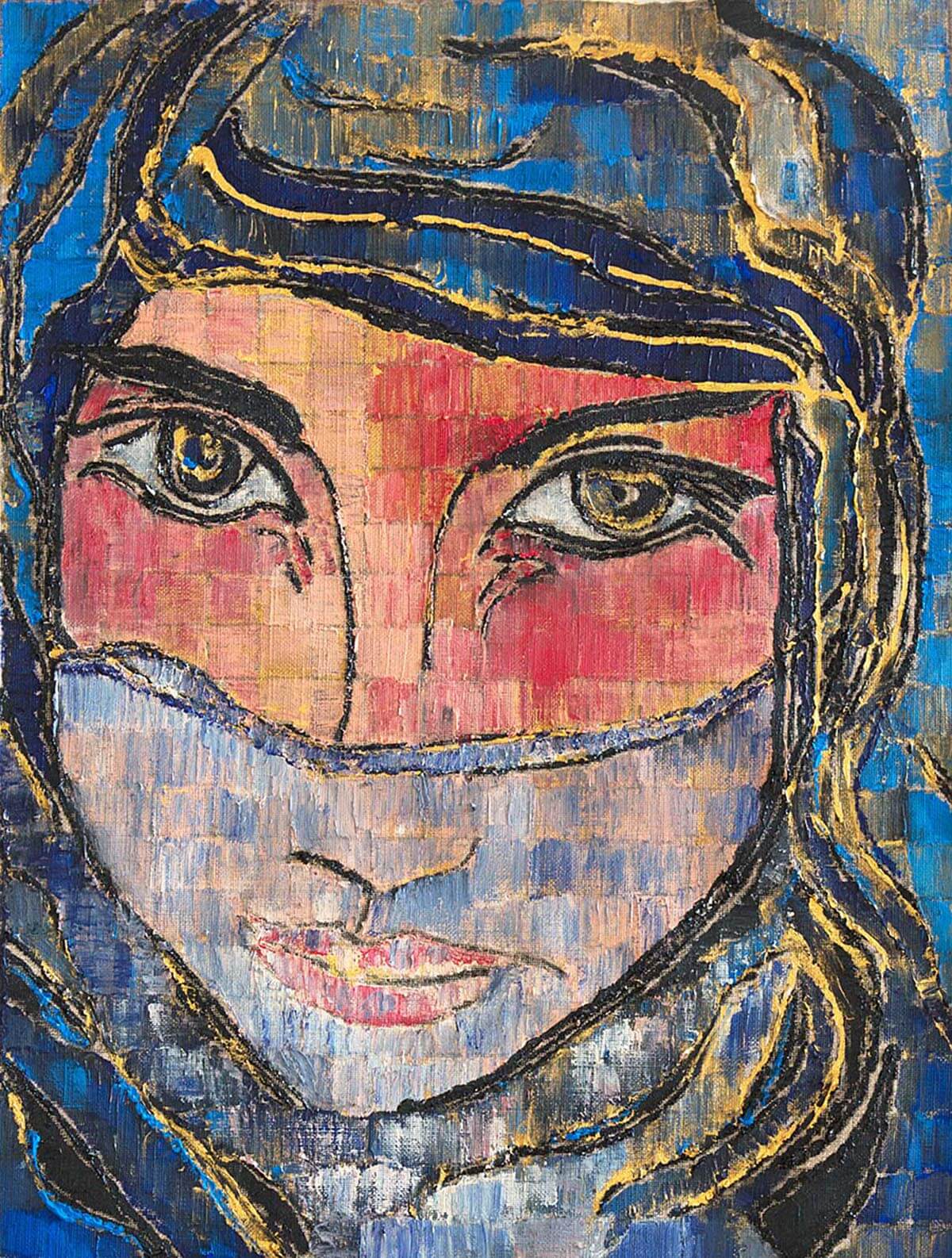

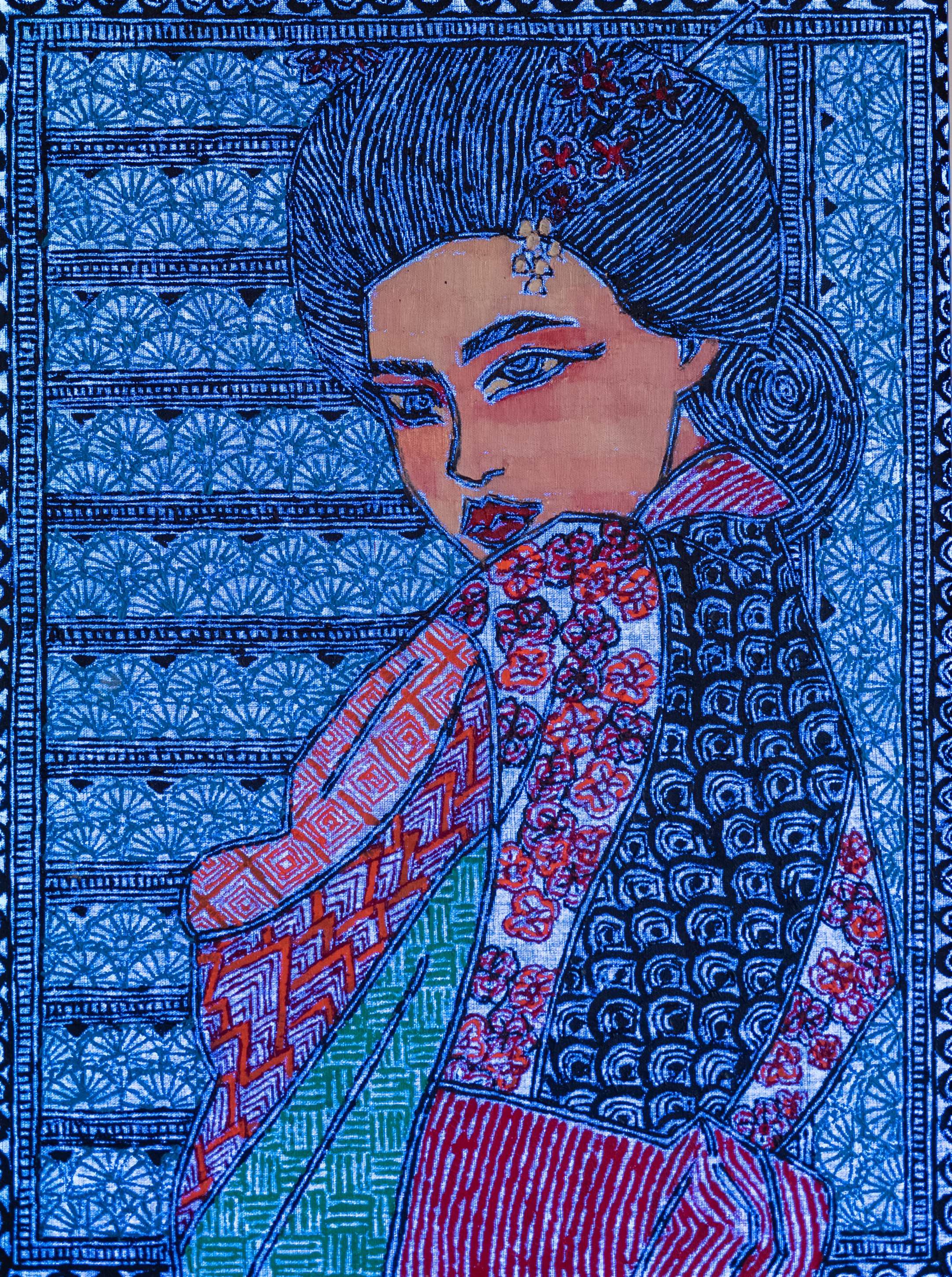

The Moroccan-born portrait artist Ghizlan El Glaoui works out of a studio in an area of Chelsea with impressive pedigree, having hosted the iconic likes of Turner in its time, and it is fair to say that her unique aesthetic points to a more classical era of painting, while simultaneously bringing modern technology, quite literally, into the frame. El Glaoui incorporates a cutting-edge system of backlighting into her portraiture that is designed to give her subjects an all-but religious aura – elevating them to near-saintly status, and reminding us, philosophically, at least, that it is though the cracks where the light gets in. Born into an artistic family in Morocco, with Royal heritage, she spent her formative years in the studio of her father, the world-renowned painter Hassan El Glaoui, and was deeply immersed in art from a very young age, often being the subject of her father. However, it wasn’t until she studied at L'Académie Charpentier in Paris, that Ghizlan first developed the use of light and colour that have witnessed her become, among other things, the current artist-in-residence at the Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation – where she has once more focused her eye chiefly upon her Berber heritage, in order to capture the essence of what she refers to as the ‘sacred feminine'. In this rare interview with Culture Collective, the artist shares insight into both her past and her practice, and tells us why the modern world should be far more open to learn from ancient indigenous cultures, which are oftentimes so much better interwoven with the seasonal tides of the natural world.

Why are you drawn to portraiture as a medium, and, in terms of art history, what kinds of artists would you say you are most inspired by?

In many ways, I have stayed very much influenced by a lot of classical artists, and, I suppose, the notion of the muse. I think perhaps that sense of being drawn to portraiture as a medium comes the fact that when I was young my father painted me non-stop – I mean, I have something like fifty portraits of me, at every age. And I inspired him as a muse, because of a mixture of intangible things – maybe most of all because I was always very calm around him and because I was fascinated by painting. I was sometimes even saying to him, ‘Come on! Let's go and do a portrait’, because I was just so fascinated by the atmosphere that would be in the studio while he was working.He never taught me to paint, but I suppose I just always felt like I knew the subject of portraiture. The main concern in my father’s paintings was always people, horses, ceremonies, and traditional costumes, but I’m really just interested in the face in my practice, because I felt that atmosphere or tension when he was painting mine.I also always wanted to do something very different to my father, which was the big motivation behind creating my own style, and I always have this aim in my work to show many faces in one – especially in the faces of women, because they are so often multitasking in their lives, being mothers, daughters, wives, and career women. All of these roles represent a different facet of their personality, so, what I try to get with my changing point of light is this sense of movement and flux, so that as the light changes, you can see many emotions.

Why does light play such an important role in your work, and why do you focus much of your portraiture upon Berber women?

By definition my work is intended to make the subject shine –my system of back-lighting is intended to have a kind of saintly or religious feeling, and when I choose my subjects, I tend to choose people that I want to make shine again, because, let’s say, their culture has disappeared from people’s memory, or because I feel huge admiration for them. In that respect, the Berber culture is natural for me to focus upon, because my family were Berber – an indigenous culture that has been decimated over the years by invasion, colonisation, and so forth. It is the ancient culture of a people who were so in tune with the natural world, and who could live on this planet without destroying it simply because the rhythm of their lives was so much more in synch with nature than ours is now. That original Berber culture has been obscured much in the same way that the Native American culture has been – another race that had a beautiful way of life, and who have a similar beauty as the Berber people in their relationship to spirituality, and the sun and the moon. I just believe that there is real beauty in taking something forgotten that you respect so deeply, and making it shine, and what I really want to highlight in my work is always this sense of depicting something that truly touches my heart.

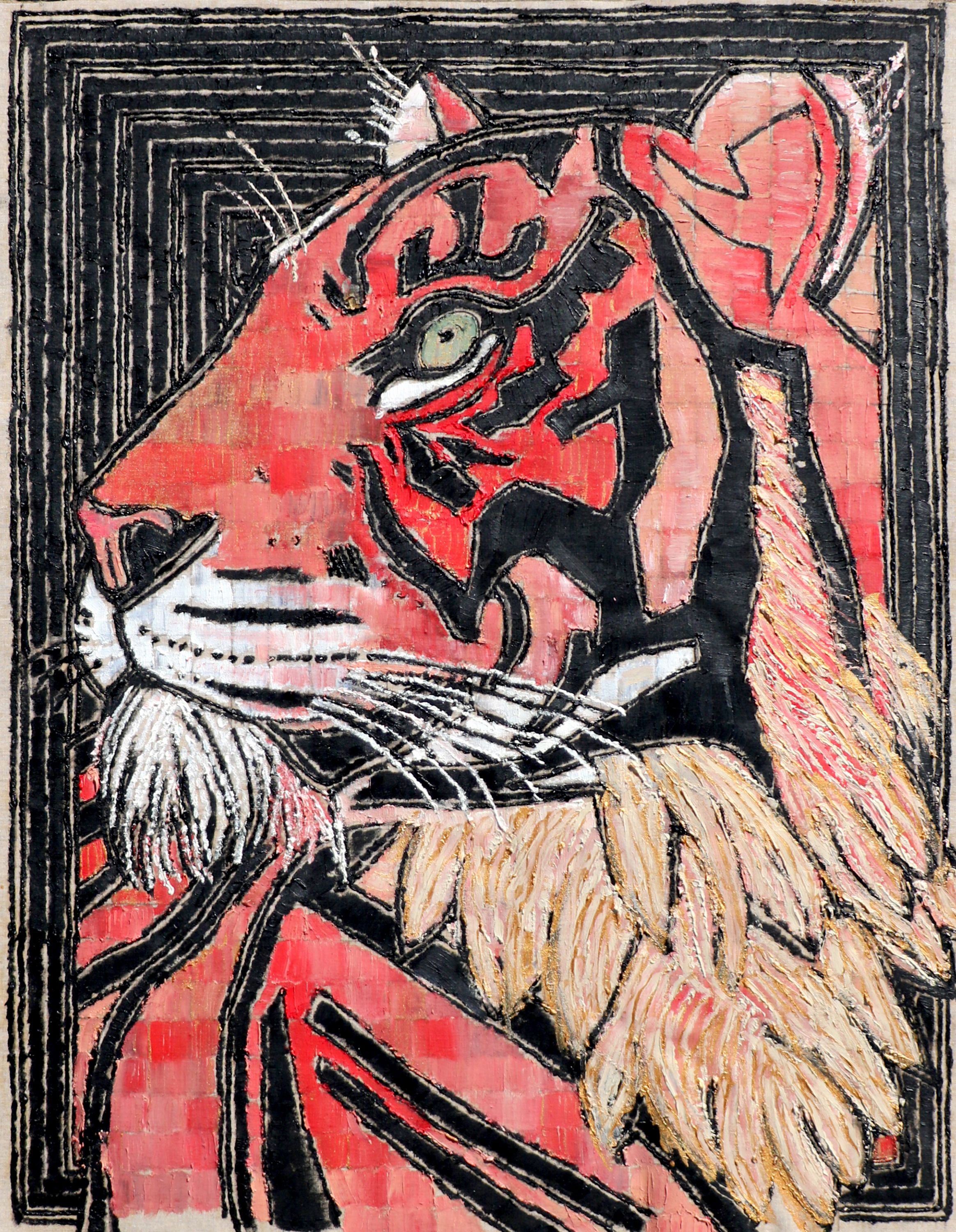

And why are you also very drawn to depict animals, particularly horses?

Well, my father is the Picasso of horses, and is famous across the world for his horses, so for a long time, I really did not want to even touch the subject, because, of course, when you are a daughter of an artist, they wait for you to use your father's name, and your father's prestige, which I did not ever want to do. I mean, my father could paint a horse in three lines and still provide movement and colour, and that was his thing. But in difference to him, I do not ever paint the whole horse, I just approach the horse as the portrait of a face, and when I began doing that I found I just really loved zooming in on the face of a horse to explore emotion. I also do the faces of a lot of jaguars and leopards, because of that incredible print each of them carries that is so personal, and so completely their fingerprint. In every instance, I always find that the eyes can really fascinate you, and they are often my centre of interest with both my portraits of women and animals. I love to work on that mathematical base of the golden ratio, as well – three squares on the left, three squares on the right. I come from the background of mosaic that is so ubiquitous in Morocco, so it’s almost as though the square pattern is just ingrained in me. It’s in my genes.

Given the religious aspect of the light technique in the work, would you describe yourself as a spiritual painter?

I am not a huge believer, but I try to bring myself very good karma. I do believe that there is some entity, or God, and that we all have our God we can pray to when we are scared, or when we want some guidance. It's good to know that there is possibly someone there to help you, and to guide you. I always felt as a child that I was spiritual to the point where I could communicate with another side, actually, but I didn't ever want to get there. I had terrible nightmares, and I could understand from a young age that maybe I could see things in my dreams that I didn't want to see. I would often run straight to my parents, and go to their bed, because I couldn't sleep alone. And at some point, I just decided not to dream anymore, because I felt if I couldn't control it, then sleep would need to be just that, sleep. Now, I don't remember my dreams, ever.I'm possibly too spiritual, in that sense. That's why I think I protected myself. I didn't want to be spiritual to the point of seeing people that wanted to be seen, and talking to entities that could be around. Sometimes when I am painting in my studio, I can feel the souls of people that have created here in this space before me accompanying me – because this whole area has such a rich history of artists. And I have seen in the journal of my father that he felt the same way – that there were souls around him when he was working.

Once Upon A Woman exhibits at the Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation until June 30th. All images supplied courtesy of the artist.