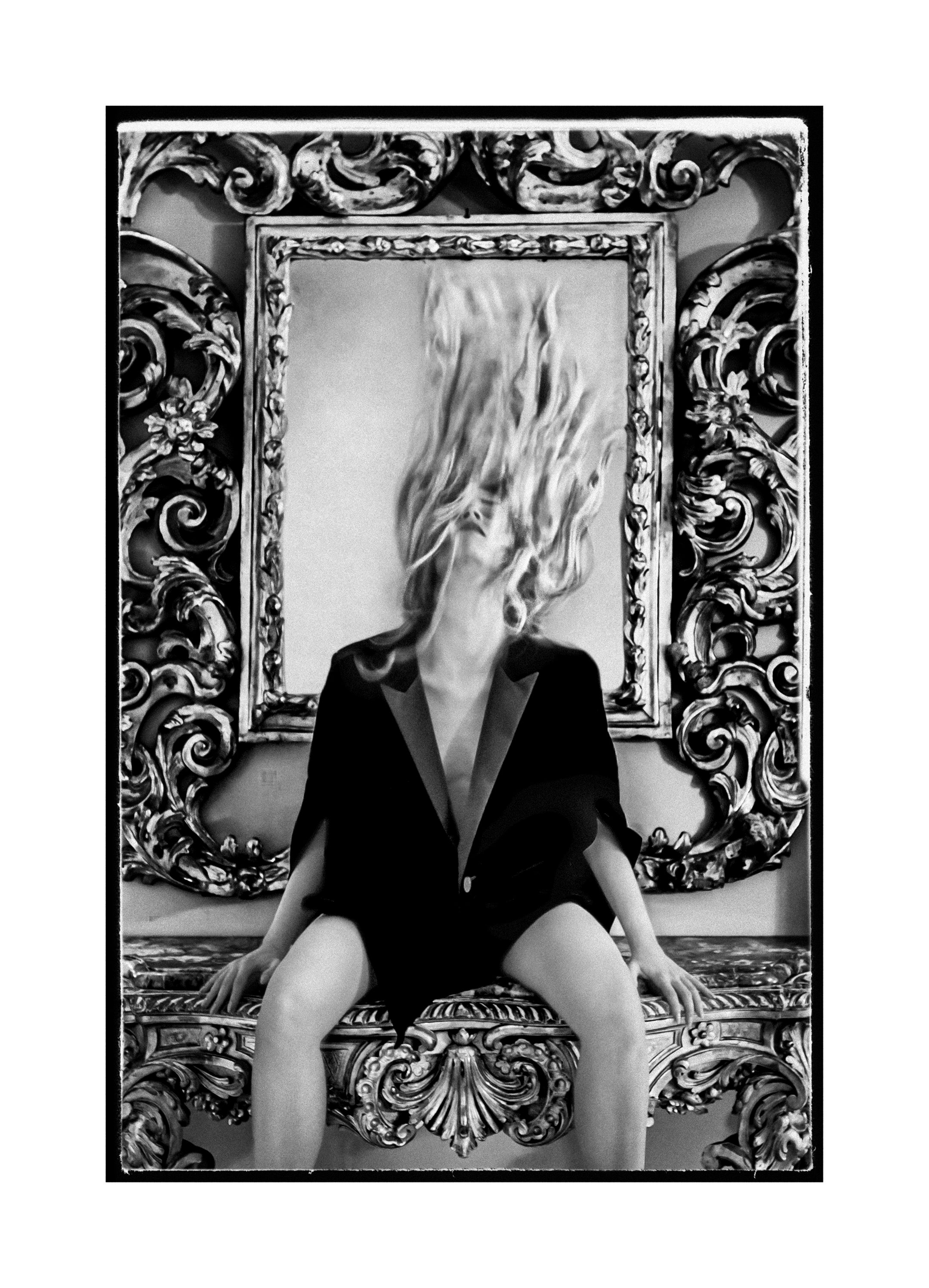

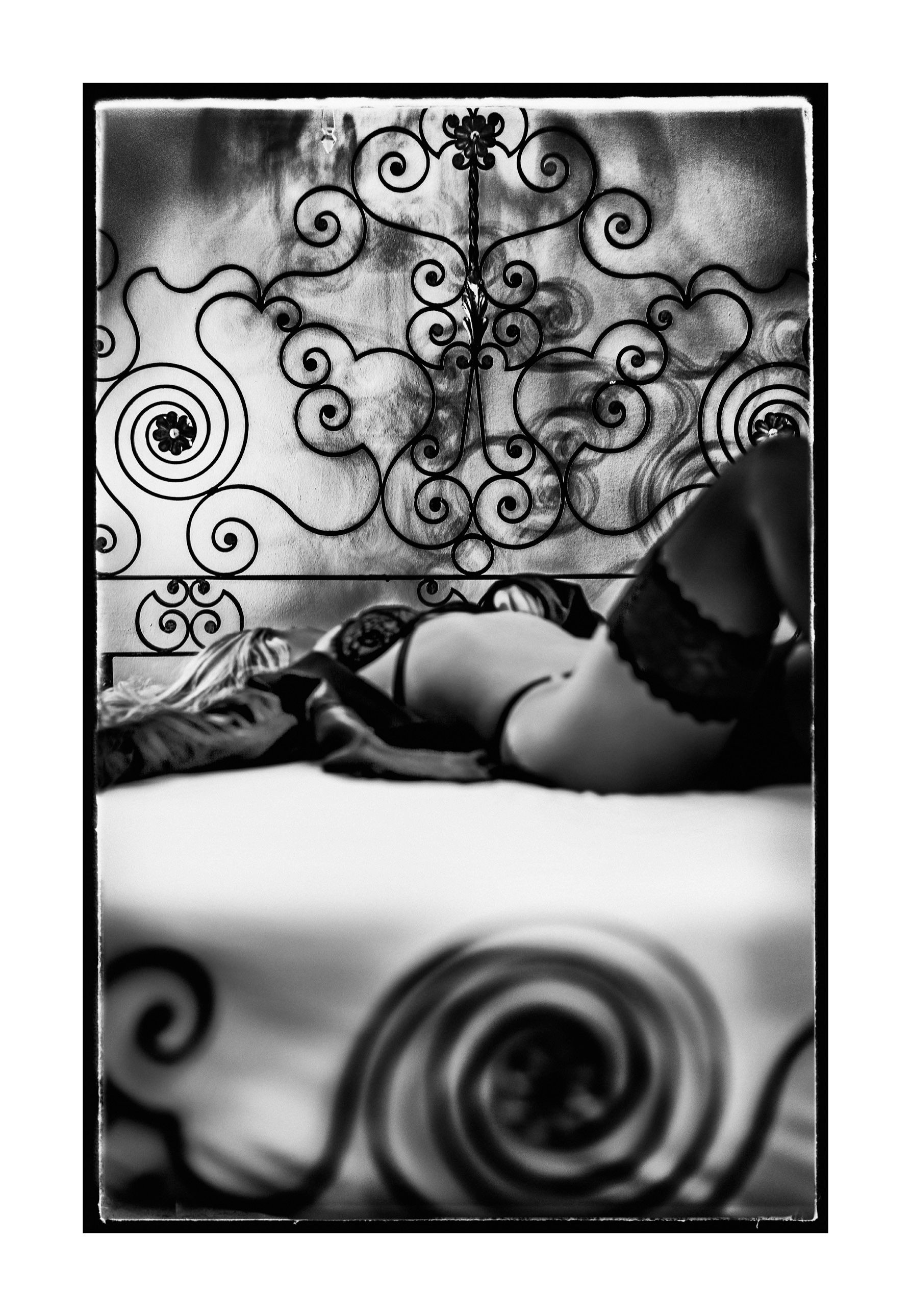

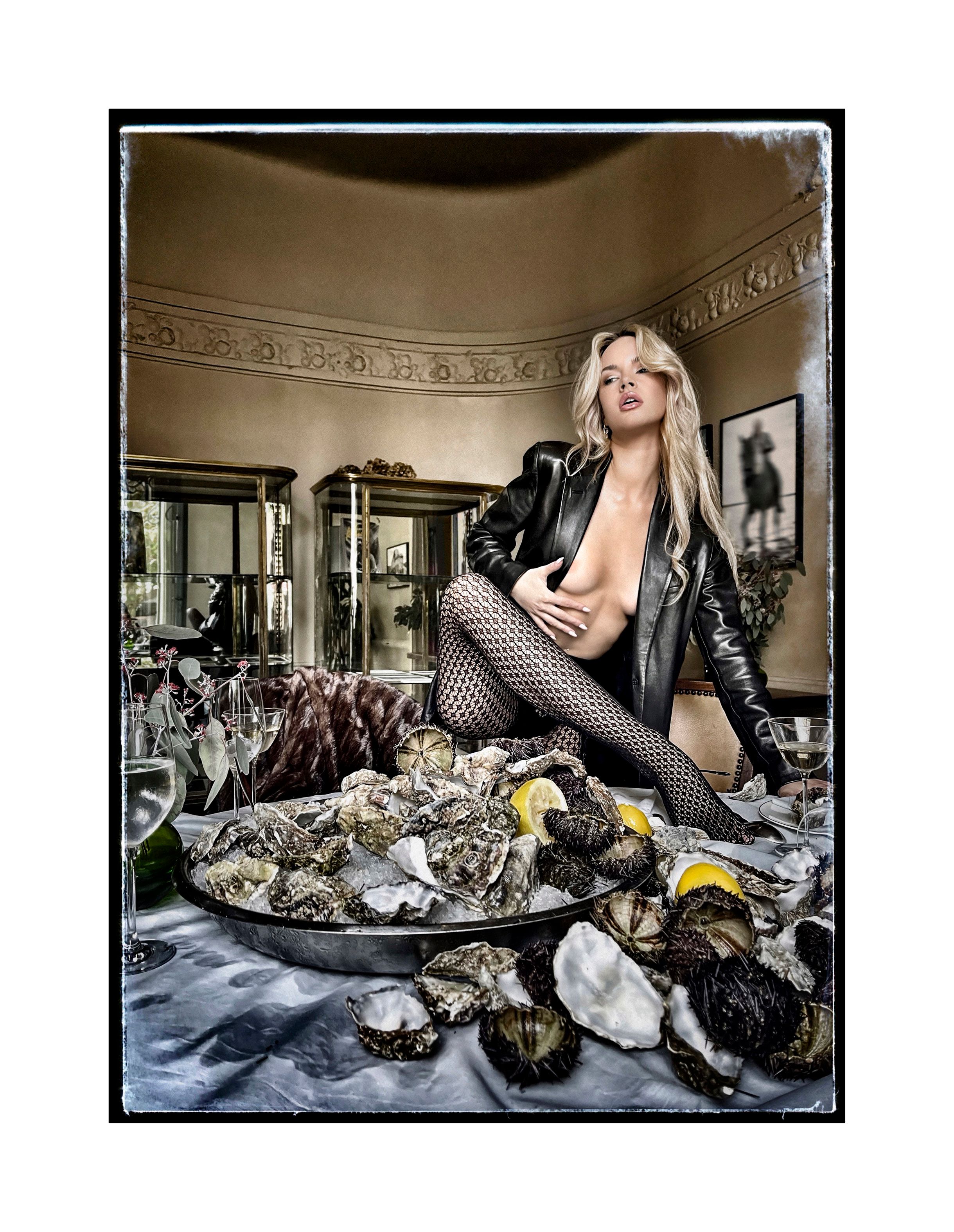

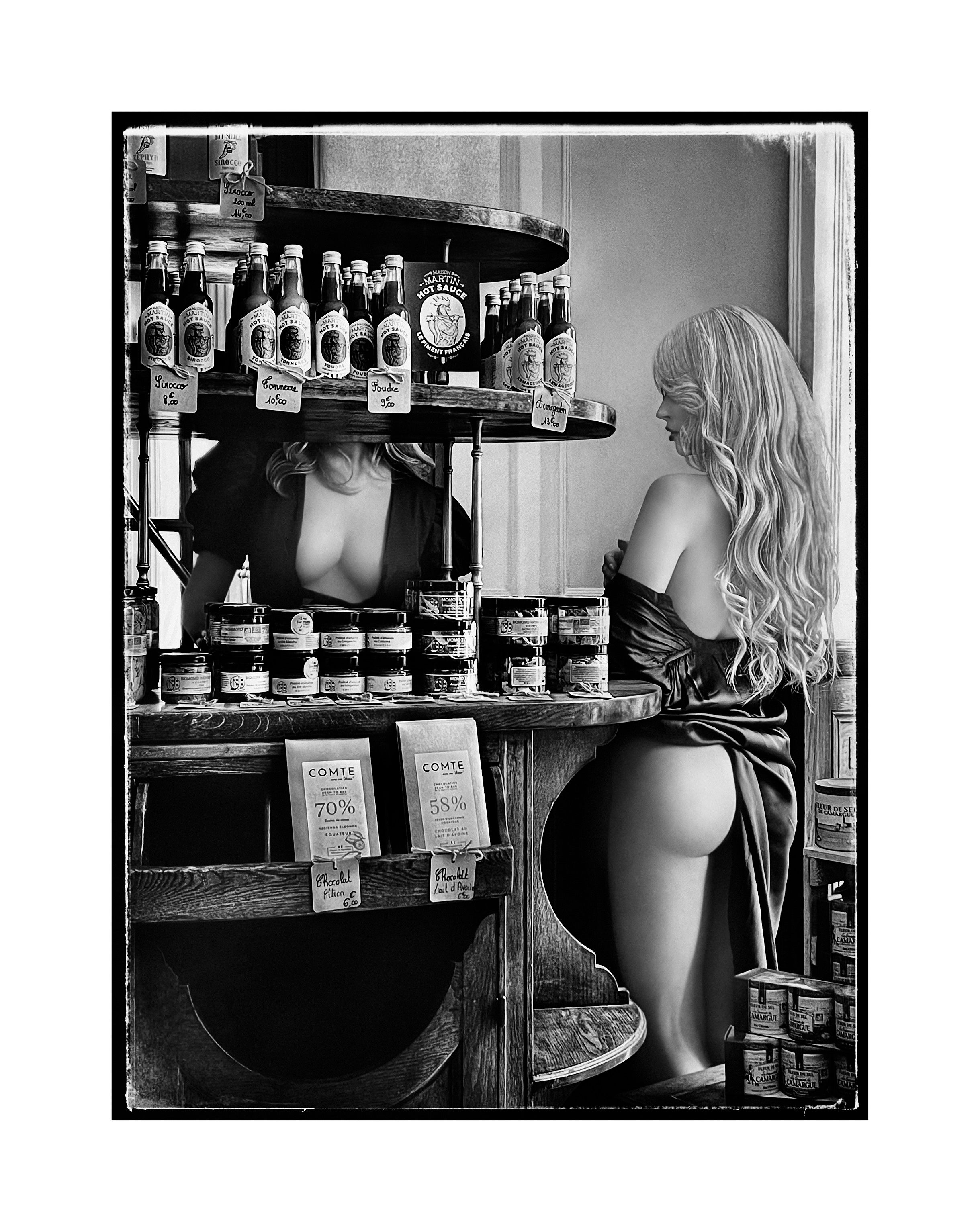

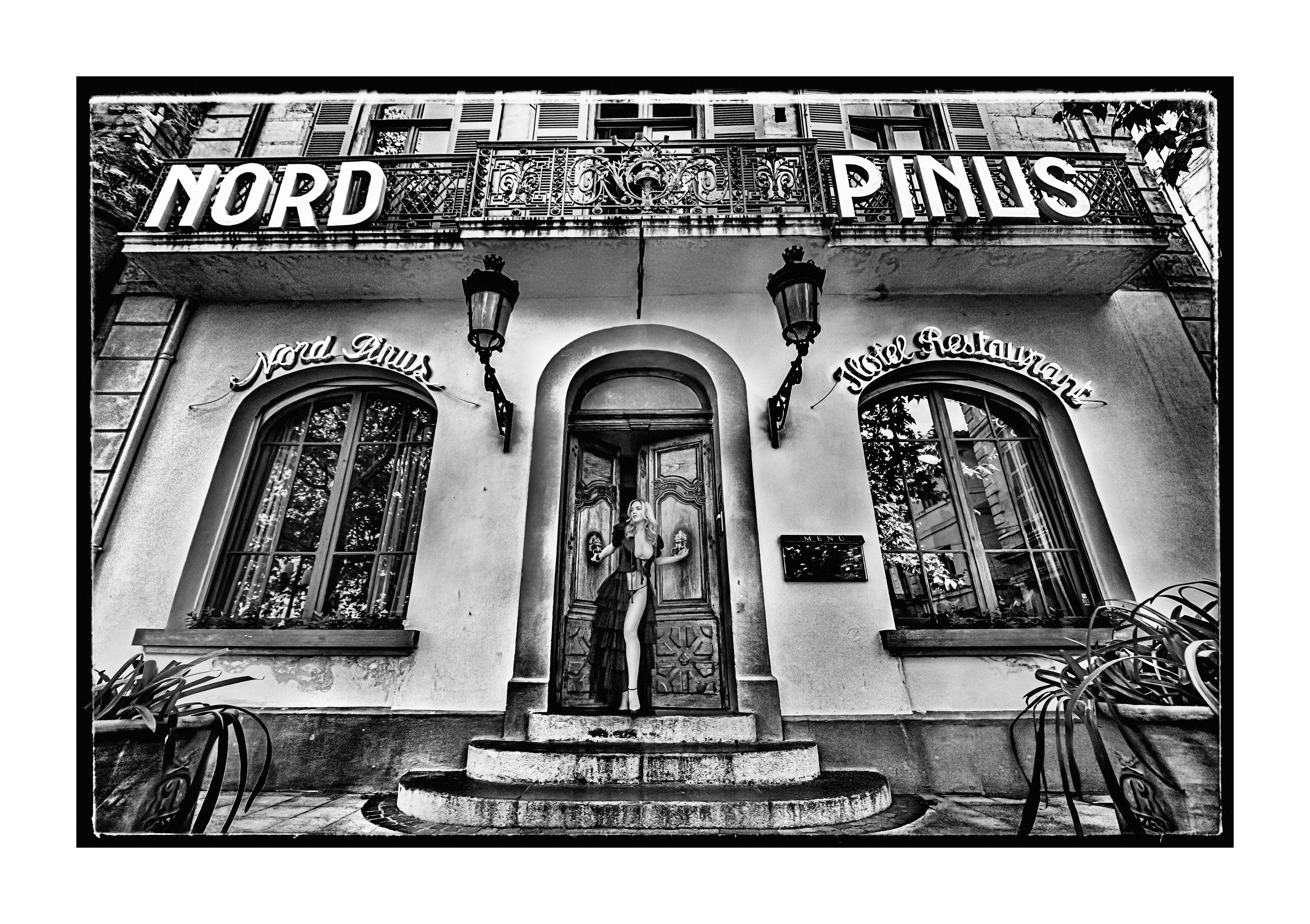

Maryam Eisler is a photographer of Iranian heritage whose lens is firmly focused upon the communication of what she refers to as the sublime feminine – a sensuous and dreamlike investigation into the female form that melds various notions of classical and modern beauty in a subtle interplay of geometric lines, light and shadow. If Only These Walls Could Talk is the latest series from this highly respected patron of the arts, and it witnesses the photographer situate her ongoing obsession in the sumptuous splendor of Hôtel de Nord-Pinus in Arles – a sanctuary infamous for hosting the likes of Picasso, Lacroix, Cocteau and indeed Helmut Newton, whose classic 1973 shoot with Charlotte Rampling in Suite 10 provided Eisler with a conceptual jump-off point for the show, which is something of an homage to the master. The near-mythical backdrop of the hotel transmits a romantic nostalgia for a somewhat more sophisticated glamour than we are perhaps used to in the modern era, and the curvature of its architecture perfectly complements the body contouring of the two dancers who bring Eisler’s unique vision to life with bold, yet understated sexual magnetism. Here, the image-maker, who sits on the board of Photo London and is known across the world for her editorials in the likes of Harper’s Bazaar and Vanity Fair, speaks to Culture Collective about her love of melancholy, the ghosts of collective memory and the lost art of storytelling.

What drives you creatively?

I think I'm a creature of nostalgia and melancholy. And I would say I'm quite romantic on many levels. I also maybe have values of a different generation – one that believes in beauty in the universal, conceptual and philosophical sense. I don't do nudes per se. I use body forms as geometry. I only view a body when I shoot, and I only work with dancers. I'm not too interested in shooting fashion models because they have a different kind of dynamic and a different aesthetic. The women in this series are both dancers and when you work with dancers, it’s always a very different situation in terms of the muscular dynamics. Models can be a bit soulless on camera, and I am into very soulful images. When you are standing in front of my work, I want you to have an emotional response to what, for me, are painterly photographs – I want you to have that inner feeling of warmth, nostalgia and melancholic passion you might have with a beautiful painting.

It sounds like a meditative process…

I do tend to use photography to kind of centre. I definitely go through a Zen moment when I click. I lose myself in the moment. There is a meditative element, because it's all about shapes, curves and shadowing, and, for me, that is a combination that has everything to do with collective memory – memory of a moment that you may have spent, memory of youth, potentially, or even lost youth. I'm playing with, dark and light and creating linearity. There is an element in this series of using the body and the surrounding architecture to create a sense of spiralling into the past. The beds, for example, have all these spiralling shapes in the frame, and have been at the hotel since the very beginning. At night, when you have the candles lit, you get these incredible elements of shadowing, which works beautifully in black and white. When you combine all of that with the figure, both forms just become lines, and you may not even be able to see the body. There is also one image in the series where the subject is enlaced around a staircase, curling around it and almost holding it, so there's a sense of enveloping the space – an element of sensuality in both the person and the space that's depicted.

What drew you to shoot at Hôtel de Nord-Pinus?

I love so many elements of the iconic architecture work that are particular to the hotel. I’m also very aware of the importance and significance of hotels in visual culture – there are so many different hotels where really interesting things have happened. And this is just one among so many stories. I love hotels because they have got this transient thing of people coming and going, and leaving marks, and that also has to do with memory. I think there is this accumulation of collective memory at hotels, you know? It's almost like you're stamping the memories of people upon the space – the DNA they've left on walls and bannisters, memories they've left on sheets, memories they've left in the restaurant, in the bar, in the café, in the conversations that have been held ... Imagine if you could take an aerial view of all these personal stories of sadness, happiness, passion – all stamped upon the space over time. Hotels are very potent places. They're very rich. Hotels are also sanctuaries, of course – places where you can get away from your life; get away from your reality. There’s a storytelling that you can read into all the images, and I leave it to the viewer to decide what the story is. I'm a great believer in building a story.

What made you want to create the homage to Newton’s original shoot with Charlotte Rampling in Suite 10, and what do you love about Newton in general?

I would never dare compare my work to Newton's, but he was definitely at the origin and inspiration for the series. I was myself somewhat spiralling into these spirals and curves when I was shooting because it was such a privilege to shoot there. What I really love about Newton is his incredible ability to tell a story, which is on another level. His images were playing my head when making these works, and I've used elements such as the mirror and the console that Charlotte Rampling sat upon in suite number 10. I wanted to talk about timelessness, in a way. Charlotte is so timeless in that shoot, which really shows that there's beauty in every age; there's beauty in every generation. For me, Newton’s women are always depicted as quite powerful – they always own it, and are comfortable in their skin. The way that they're standing is actually sometimes almost violently powerful – owning a lot of sexuality and presence, but potentially lacking some sensuality.

What is the difference in perspective when a woman is looking through the eye of the lens?

I am very much a believer in the difference between the male and female gaze, and this series is definitely a female perspective on women – there is an element of sexuality, but without it being overtly in your face. I want to shoot in a way that is flowing, floating and potentially poetic. There's no objectification in what I refer to as the sublime feminine. I think you can be a feminist and at the same time you can own your sensuality and sexuality, and not feel like you have to adhere to certain, dare I say, overly woke definitions. I feel that both the women in this series are very voluptuous. They’re sexy in my kind of definition of sexy, and they're not shy of it. There is very definitely a capital W in my definition of woman, but not necessarily in that modern and quite raw kind of way.

What for you are the key criteria of a strong image?

The first level is emotion and then comes the storytelling, which allows you to start dreaming. It’s always about something that you're emotionally responsive to without really necessarily having to understand it. If I choose then to inquire more as to why I like this or why I don't dislike this, then that's my own journey. But it is always that first layer that gets to me. I think that is what strong photography is about. It has to pique your emotions more than your intellect, let's put it that way. It's first and foremost got to be emotive before you get into the more intellectual side of things. If I stand in front of something and it does something to me, like, literally hits me in the gut in a good or in a bad way, then that is what gets me.

If Only These Walls Could Talk exhibits at Alon Zakaim Fine Art, 27 Cork St until November 22nd

Images (Top to Bottom): La Lionne; Quand Les Cheveux s’Etalent; Sur Une Plage Abandonnée; Une belle histoire; Il Etait Une Fois, Le Nord-Pinus. All images courtesy Maryam Eisler.