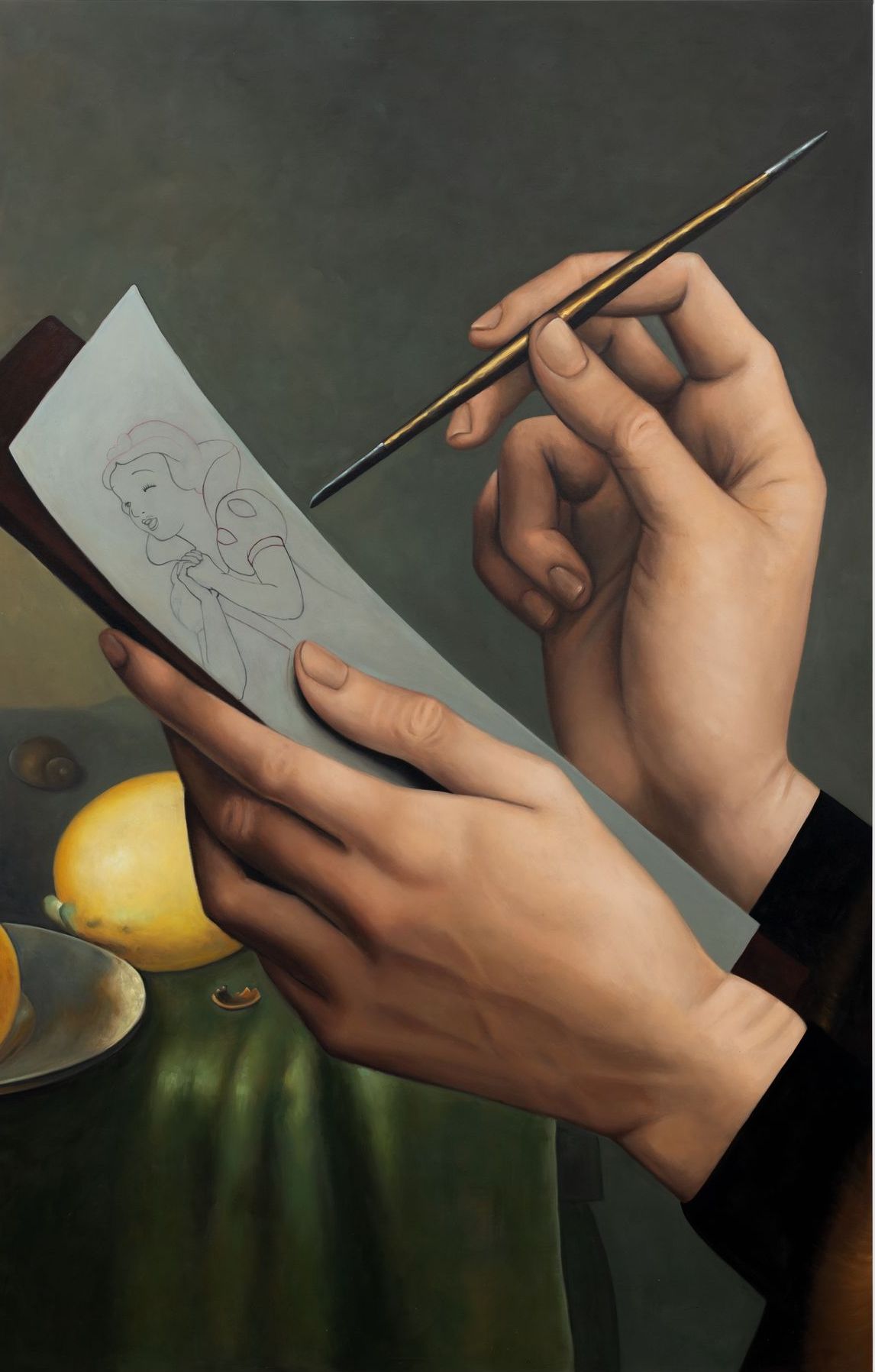

There is an obsessive quality to the work of Belfast-born painter Ted Pim, whose unquestionable craftsmanship is matched only by his unique imagination and passion for blending the aesthetics of the Italian Renaissance and Dutch Old Masters with motifs from Irish folklore and pop-infused ephemera of the the modern age. In finely executed brushstrokes Pim marries high art and the ultra contemporary, creating uncanny works of unsettling beauty that feel at once both reassuringly familiar and enticingly alien. In his latest series of paintings, currently showing at Almine Rech, Pim explores the act of mirroring, playing on the notion of the doppelgänger which has a particular resonance in Irish mythology – intricately reproducing the image created on one side as if the canvas itself were being split at a right angle by a standing mirror. In this interview for House Collective Journal, the painter reflects on his own childhood in Belfast, the enduring influence of religious iconography, and the projections we all now create via the magic mirror of the smartphone.

What was your first real exposure to painting?

I grew up in Belfast in the nineties, and it wasn’t exactly a cultural hub at that time. But my grandad used to take me to the Ulster Museum and it has a Francis Bacon in the collection called Head II. I remember being completely horrified by it, and, you know, it's the most ugly, grotesque, disgusting painting I've ever seen – even now when I look at it, it turns my stomach. It's horrific, I remember ust feeling something when I saw it as a boy, and it’s a feeling that is hard to describe, but I always feel that good art creates that feeling The other one really hit me young was Damien Hirst's A thousand Years – it's the flies and the cow's head in the container, where maggots are forming and turning into flies, and then being zapped by a fly zapper. That also created that same feeling. but when I was a kid, it was all about that Francis Bacon painting for me. As a painter, I've always tried to communicate that feeling, and if I can get even one percent of that feeling that I got from that painting over to the viewer, I'd be quite happy.

Would you say you were drawn to darkness? Were you fascinated by the grotesque?

I don’t know if I was drawn to darkness. It was just about chasing that feeling. I can’t even say that it was an enjoyable feeling, but for painting to do that to someone is pretty remarkable, and it's something I always think about. I've never really thought about why exactly I've been drawn to painting and the old masters in particular. I grew up in a working class catholic background and in my area, everyone had reproductions of Jesus painted in old master style in their houses. It was as if every wall I saw had something to do with religion, so my childhood was sort of saturated by the iconography, and there was always a sense of life and death in the art . It was very segregated, and the community was so controlled by the church, and the sense of importance tied to identifying as an Irish Catholic. I'm not religious, but the Catholic church did do a lot for art in general, you know? They commissioned so many great paintings and great artists. The iconography of the church was so interesting to me, especially with the juxtaposition of living in West Belfast. It's such a polar opposite.

Do you feel your identity is something that is like a stake in the ground that one create, or do you feel like one's identity itself is always in flux and juxtaposition? Does your painting reflect that?

I think it's probably always a state of flux. But especially where I come from, identity is such a big thing – people die over identity, and there are a lot of people who have placed a stake in the ground. I'm not sure how healthy that is, but a lot of people feel it's very important. I think a lot of people just feel like they need a sense of belonging, you know – even if you look at football as a marker of identity, and as your there is the sense of this is who I am and I die for this club. It’s not for meIn terms of painting, ultimately, I'm painting for nobody else apart from myself, and it is a form of escapism into sort of creating my own world. I've joked in the past that my paintings are sort of like what might happen if there was a library and there was an old masters section, an Irish folk section, and a Disney section, and it was blown up. I would be the guy that would go in afterwards and start to piece everything together to create a sort of future reality.

What drew you to the mirroring in your latest series, and what have you learned from the process?

Well, I learned that it’s really difficult to create a mirror image (laughs). With all of my work I tend to go down a rabbit hole of the idea of history repeating itself and transforming. In terms of the mirroring series, I feel like the world in general at the minute is in a state of change in terms of empires falling. I don't know if that's just from the media that sort of creates a feeling of uneasiness, but I feel like we're in a state of transformation. There is a kind of uneasiness in mirroring, and a sense of unfamiliarity and I started to think about the idea of repeating imagery – creating a world that's not fully crystallized to sort of hold up a mirror to society of what's actually going on.

Do you have a definition of beauty, especially as such a fan of the Old Masters?

I don't have a definition of beauty. It's feeling based, for me. I certainly can find beauty in a lot of different things, and I'm drawn to certain images, but I don't think about why very often. I will rip out a lot of pages from books without considering what the context is or what the meaning behind the images is. I just look visually and if I'm drawn to something, I'll then use it in my painting. I suppose beauty is always transforming –currently we’re being told what beauty is by the media, a kind of beauty as it is perceived in fashion or glamour, but if you look at the Old Masters then it’s clear that what they perceived as beauty is totally different in outlook. It’s a strange world we live in now, and social media is even changing what we think of as beauty – in the past five years, you can see how people are starting to look like an Instagram filter in real life, and that in itself is quite a frightening kind of mirroring, because it plays into people's own insecurities.

How do you feel about the rise of generative art and AI?

When it first came out, I probably felt a bit threatened, but I have been speaking to artists who have now embraced it, and one particular director who has started to use it to create storyboards. I can see how people are using it to sort of help the process. I feel like real art is all about expression, feelings and ideas, though, and AI does not have that, so the more I think of it, I'm not threatened at all. I can certainly see why certain industries should be afraid, but I'll still paint no matter what, you know? Even if AI art does exist and people are respecting that as an art form, I don't really care because I'll still be going to the studio and painting – I go into the studio everyday and paint nine to five and nothing will change that.

Never Odd or Even exhibits at Almine Rech, London, until May 18.