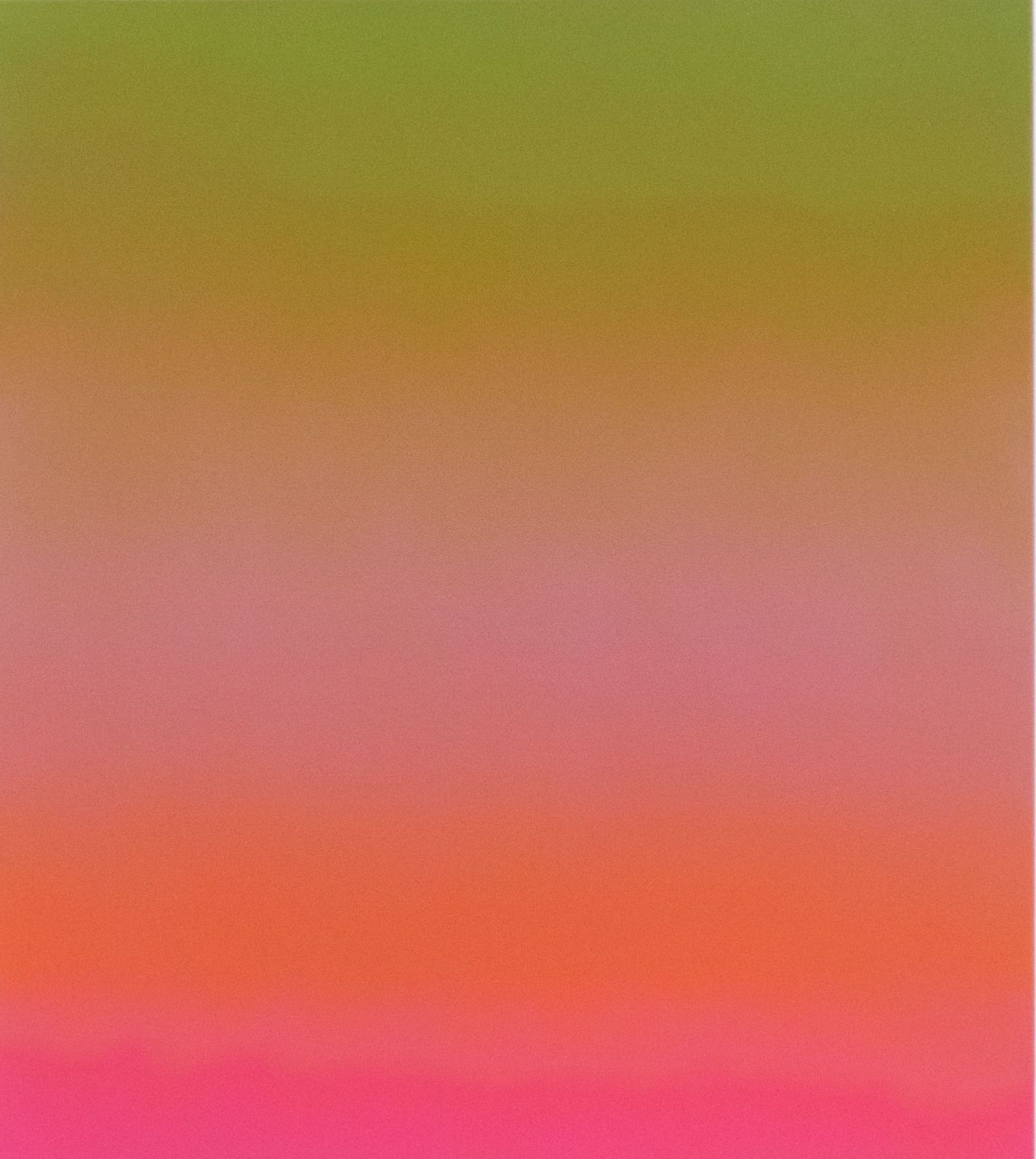

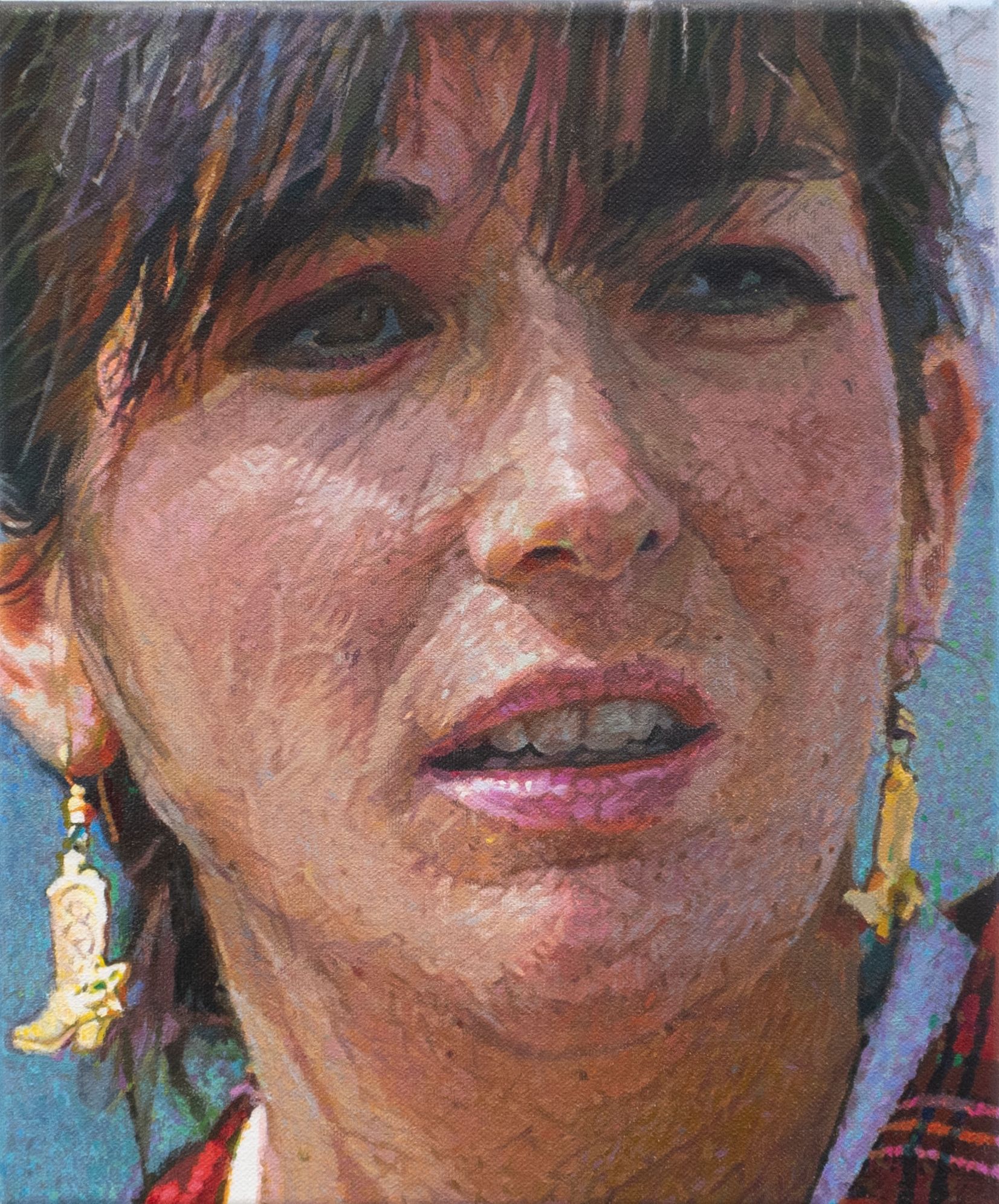

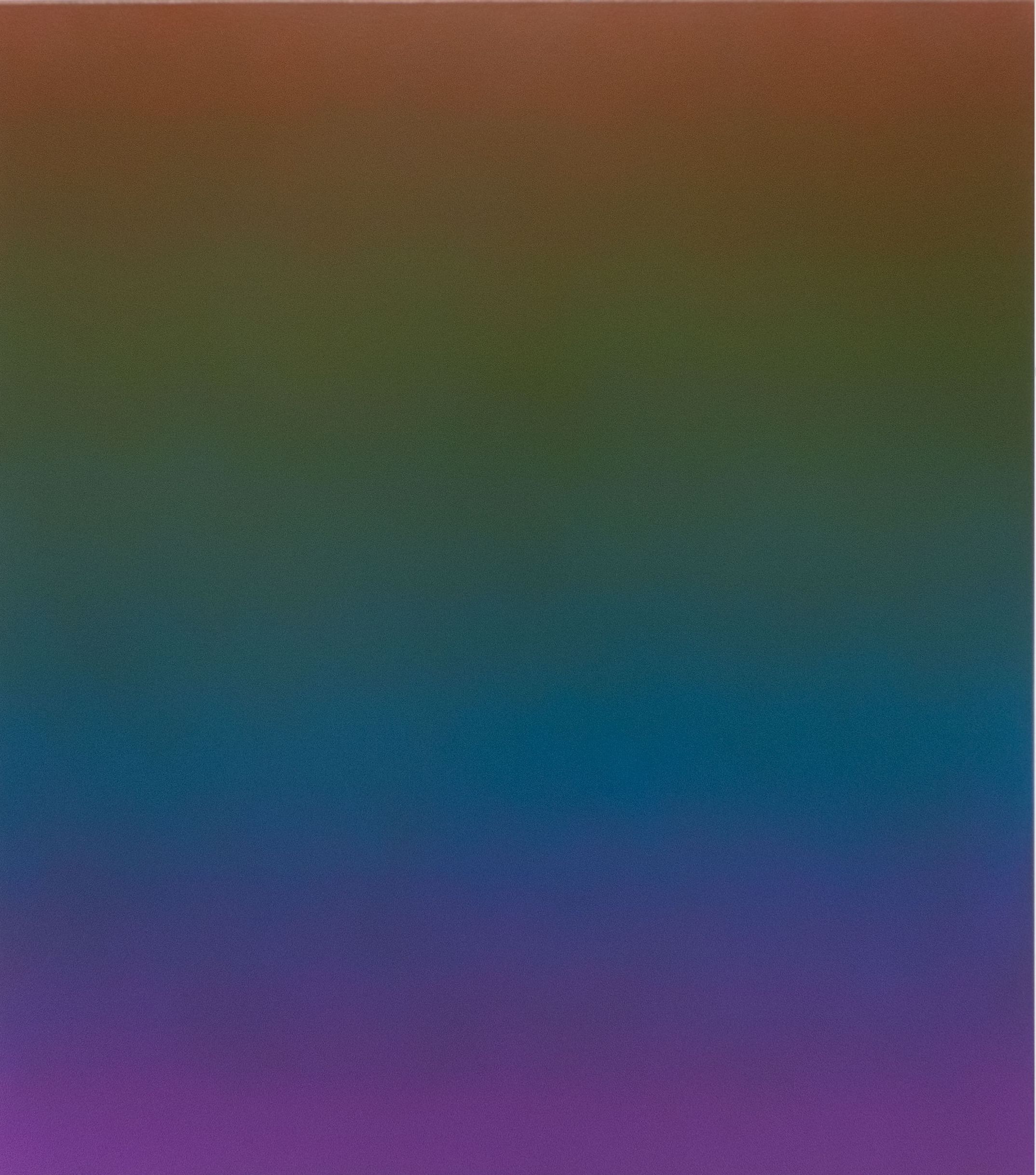

Boo Saville is a British artist whose work is perhaps best known for its deep dive into mortality, and inimitable investigations into the intangible vagaries of perception. Never one to be easily pigeonholed, the utterly mesmeric colour fields for which she is widely celebrated consist of effortlessly gradating shades, in which multiple layers of paint create something akin to an ethereal doorway to another dimension. Conversely, her figurative works, which are largely the outcome of online search binges, are incredibly sparingly painted, retaining the weave of the canvas. Saville’s latest exhibition, simply entitled Her, presents the colour-field work alongside iconic paintings of women drawn from a collective consciousness that could be said to have been induced by the tabloid press – thus the visages of Ghislaine Maxwell, Princess Diana and Amber Heard seek to draw an empathetic emotional line between the viewer and the persona caught in the frame, whose emotional distress provides a gateway to our own feelings. In distinct contrast, the intensely beautiful colour-fields, named after women the artist knows personally, invite us to mediate on our own being and interpersonal relationships via abstraction. When presented together, these conflicting works examine the way in which we perceive and respond to images of women on a personal level, and also ask questions about the way in which the media-at-large chooses to portray women – asking us to consider how much we both absorb and project via overwhelming exposure to certain imagery. Here, the artist talks to Collective Culture about the meditative aspect of her practice, the female gaze and our collective passion for disaster.

What attracted you these tabloid images of famous women, and made you want to recreate them?

In lots of ways these momentary images of women refer to my own memories. They’re kind of mimetic in the sense that they represent something to me from the past, but I tend to just actually make them before I reflect on what they might mean to me, and sometimes I discover a strange sentimentality. There was a moment in my life, for example, where that image of Daniella Westbrook with the missing septum was everywhere, and I suppose I painted her because I feel quite fond of her for actually making money off that image, and have a nostalgia for those days when people were much less careful about appearing to be doing anything that could be get them cancelled. It’s just very interesting to me how these images of women have kind of stuck in the collective consciousness, and they are all such divisive figures. It’s quite random how I come to them, though. In the case of the Ghislaine Maxwell portrait, the only reason I came to her is because of the earrings she has on in that image. When her father died in mysterious circumstances I clearly remember her giving a press conference to announce that he had died wearing these absolutely massive cowboy boot earrings, and feeling it was such a strange choice – and the image was then so prevalent in the tabloids. When my own mum died, one of the men carrying the coffin had very sparkly diamond earrings on, and there was some connective tissue between the two things for me. It's weird, but there is often a very minor detail that I focus in on that can be the catalyst for work.

Is there something you were seeking to say about projection and the female gaze in the portraiture?

Well, the female gaze has always been quite a political thing in culture, and the thing all the portraits have in common is that in each of them the eyes are looking in different directions, and that they are all celebrity figures who are a step removed from reality – no one really knows these people, but via the tabloids they have come to represent something. At the time of the Amber Heard versus Johnny Depp thing, for example, everyone was talking about Amber in terms of crocodile tears, and if you Googled 'fake crying' at that point this image of her in court would come up where she looked really kind of ugly. I just thought she looked so broken, and, of course, there was then all of this attacking of her going on in the press that had absolutely nothing to do with the trial – people saying she was a terrible actress, and whatever, whereas Johnny was being talked about as this amazing actor. I mean, they were both obviously abused and abuser in a really toxic relationship, but what I found most interesting of all was how much people were projecting their own experiences into the whole thing. In a way, that's how I feel all these portraits work – all of the emotional states being portrayed are understandable and have that sense of recognition. In the image of Diana, there’s a similar projection in that way that she looks kind of bored wearing her crown. It's almost as though these are moments captured that make you go, oh yeah, I get that. I very much feel empathy for these women, in some way – and maybe there's also that sense of witnessing disaster in there, where you feel anxious about your own life, and therefore if you look at an experience worse than yours, it kind of makes you feel better.

Talk to me about the colour-field works, they seem quite meditative, are they intended to alleviate anxiety?

The colour-field pieces are based off friends and family, which is really nice, and I've become a much more mathematical in the way I create them over time. They're much more abstract, and I have this tendency to be making them and then go, no, I need to describe something, and then go back to the portraiture – it's like I get frustrated with one and turn to the other because I have this almost split personality. The colour-field paintings are like a metaphor for a person, and I enjoy the simplicity of them. When I am looking at them they feel like part of me, or remind me of someone I know, so they're very sort of very pure and personal. They are meditative to make. I spend a lot of time mixing colour, and figuring out where the colour starts and ends, and the brushwork is almost like I'm doing what a computer or a printer might do on a grid system. In the past, there has been a very glossy sheen to them, but I've taken that out now because you can get much more colour saturation and depth without – a delicacy, where you can kind of can really enjoy them without them reflecting back at you. I suffer from anxiety a lot of time, and I have stuff in place to manage that, so the meditative aspect of the colour-field work is energising for me – it feels kind of like an electric charge, because you can actually make something bright, and maintain meditation. In my personal life, I practice the emotional tapping technique, which is really effective in changing your brain patterns and calming down anxiety, and the way I use the brush in these actually acts a bit like tapping for me – it's this repetitive motion, and it's like you're in your head going, I'm having the best time. Even though I’ve always thought of ‘art as therapy’ as a bit of a trope, now I see it differently and think, why not? Why can't it also be that?

Your work seems deeply personal, what would you say has been the most transformative thing to happen in your life that has impacted upon your creativity as an artist?

Things definitely have happened in my personal life, which have remarkably changed the way I work. I've had a lot of issues with mental illness in my life, and grief, but I’ve come to find a way to love and have an understanding of that. When I was a lot younger, I was very into images of death. When both my parents died very close together, doing that early work looking into mortality actually put me in quite good stead for that, because I had read a lot about different cultures and how they approached grief and bereavement differently. When I was faced with grief it just completely just revolutionised how I saw things, and I think that's when I really shifted my angle, and became much more confident about what my intentions are as an artist. It was defining, because when you make abstract painting, all you really have is a kernel of intention, you don't really have a template for what it is going to be like, or how it’s going to end up. All you actually have is a tiny little seed, and if that is quite strong, and you have a kind of vision, then it's always going to be an interesting process. And understanding the journey is as important to the end result. Grief was massively transformative for me in loving the journey or the process of creation. I think people generally shy away from feeling pain, but, actually, it can make you feel very much alive, and very aware of your surroundings. It's very vivid. In the weeks after I lost my mum, it turned into spring, and I remember walking and just being really moved by everything – my colour perception becoming so intense. I think when people go through near death experiences, or serious illness, or losing somebody, they often learn a lot more about themselves, or they appreciate life a lot more. I'm definitely not so fascinated by death anymore. I'm more interested in life, and what our experiences of being alive are.

Her by Boo Saville is presented by TJ Boulting and open by appointment at Salon C. Stellar, 19b Beak Street, London, until July 15. For more information visit here

Images (top to bottom): Jenny, 2023, oil on Canvas; Cowgirl, 2022, oil on Linen; Isabella, 2023, oil on Canvas; Princess, 2022, oil on Linen. All images courtesy of the artist and TJ Boulting