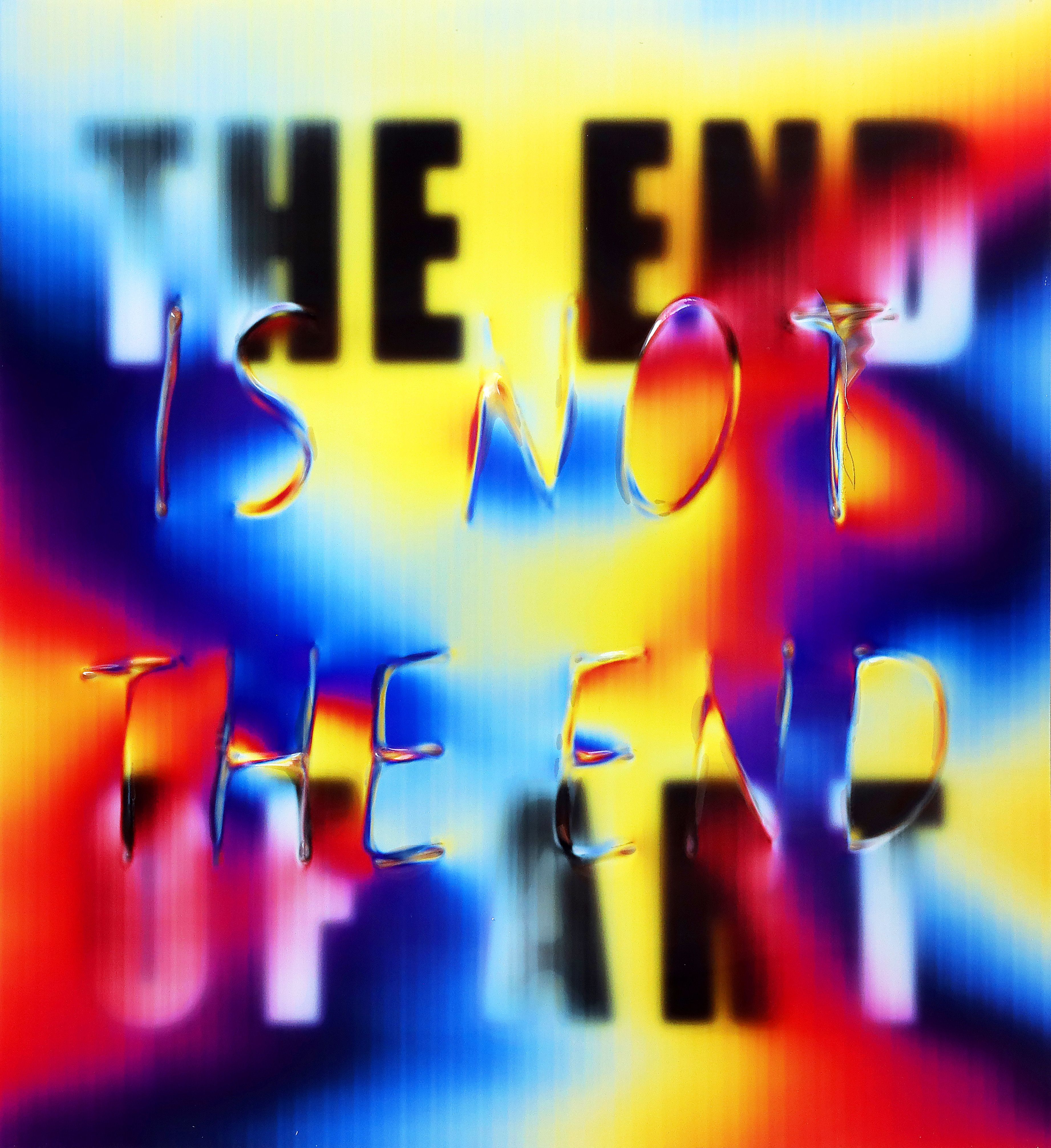

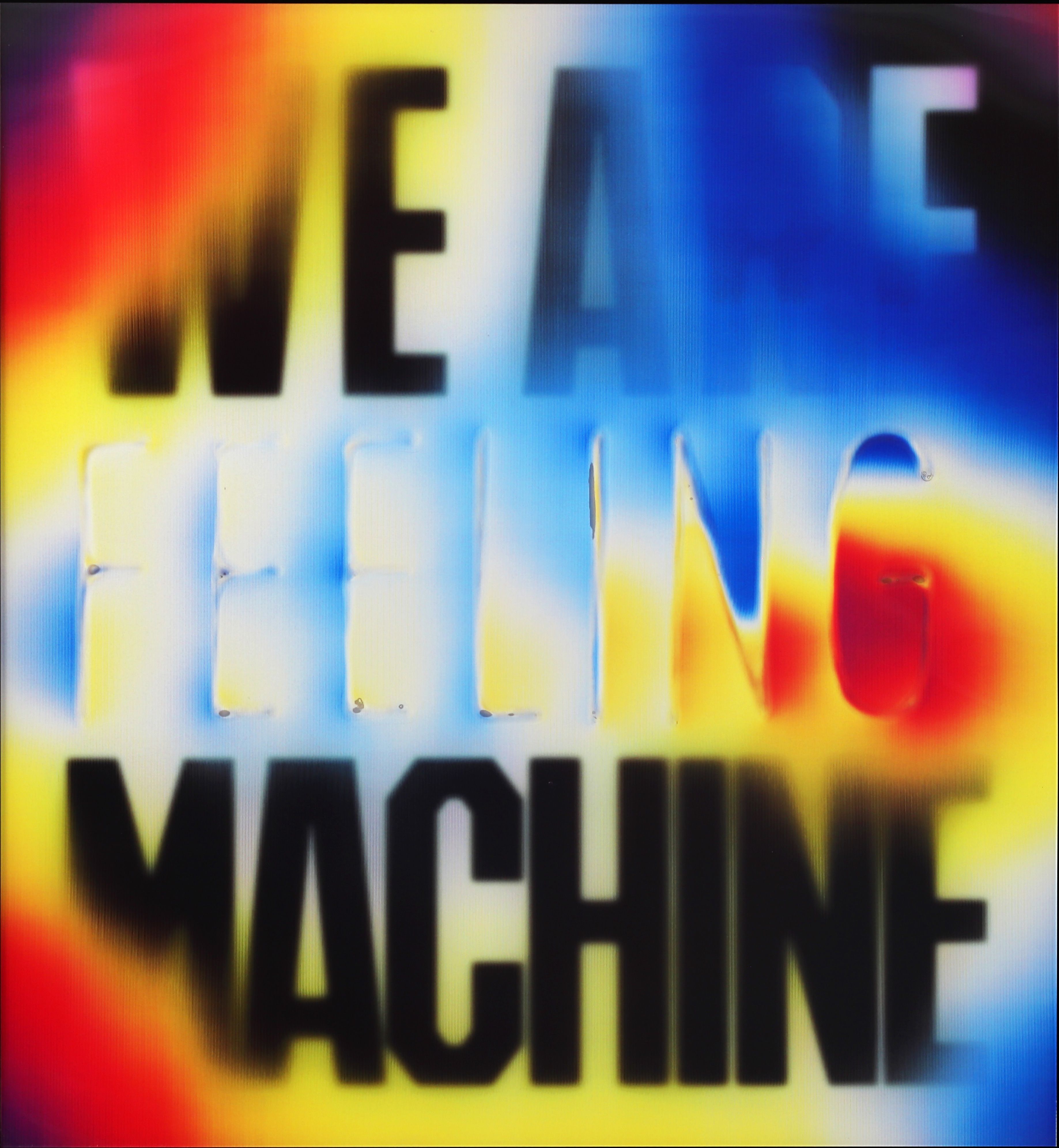

THE END OF ART IS NOT THE END is the first solo UK exhibition of celebrated French artist Pascal Dombis whose unique practice employs simple algorithmic rules to generate works of infinite complexity. His debut at Bluerider Art in Mayfair presents a stunning panoply of new works, including a series of eye-popping blowtorched lenticular pieces, and a three-metre-long interactive installation that bears the title of the show. Dombis was a very early adoptee of technology in his practice and has utilised the possibilities offered by computer tools since the 1980s, presenting an algorithmic-based practice that would pave the way for a new generation of artists. He employs excessive repetition to create geometric forms that find their genesis a simple embryonic visual that is then fed through various algorithms to generate extreme proliferation. In this interview with House Collective Journal, the artist shines a light on his desire to engage the viewer in a dance that questions perception in relation to space, time and language, and tells us why writing is a living organism.

You have been experimenting with the possibilities offered by computer tools for decades. What was it that initially spurred you on to shift from traditional painting to an algorithmic practice?

As an artist starting in the 1980s, understanding that Modernism – 150 years of ongoing avant-garde adventure – was over, was quite a real disappointment. I would have liked to continue that journey. Postmodernism, popular in those years, with its recycling and tinkering on the historical keyboard, was not for me! That’s why I threw myself into the use of computers and algorithms, as I saw it as a chance to create new visual languages and new forms of expression. My first experience of using a computer to produce art happened upon finishing my studies in 1987 at the Boston Museum School. I took advantage of attending a series of classes on techniques that I wasn't practicing, such as Video Art, and also Computer Art. However, this first encounter was quite frustrating due to the many limitations, which I felt were significant obstacles to creativity: the computers at that time were very slow, the printers were also very limited... But all this frustration ultimately proved to be fundamental in my journey, as I gradually abandoned brushes, pigments, and canvases in favor of algorithms. I had the notion that it was essential to develop works that were not subject to the machine’s technical constraints. And I still maintain, today, this critical distance towards technologies!

How would you describe your core purpose or mission as an artist - what ultimately are you seeking to communicate or shine a light upon?

Questioning the world we live in! I would say that my artwork explores our relation to Time. The time of digital machines, regulated by their pure presence and their immediacy, is transforming our future, but also our past. To me, the real issue at stake is not the unlikely replacement of mankind by machines but more concretely, the fact that the time of digital machines is superseding ours. Overall, our society is increasingly controlled by technologies whose operations are quite obscure. I am particularly thinking of the new generative AIs, which operate as Black Boxes, proliferating at an exponential rate and almost out of control, without a legal framework, creating a truly anxiety-induced environment. It is my contention that the role of today’s artists is to consider such turmoil, to create images, to produce visual experiences and to express feelings. For example, the piece Time Cage (which is at the entrance of the exhibition currently at Bluerider in Mayfair) is made of proliferations of hundreds of lines of text related to Time, both in English and French, from numerous authors, artists, poets, or philosophers. I multiply these texts on different scales, generating dynamic feelings of immersion, vertigo, and infinity, allowing the emergence of an experience on temporality from a text reading dynamism. The whole piece is cut in vertical bars which, from a distance, can be read as the word Time Cage.

Works such as Time Cage or U.T.O.P.I.A question the future evolution of the written words. How do you think the age of AI will transform language and human interaction for better and for worse?

I see writing as a living organism. Burroughs viewed it as a virus. Writing was born a few thousand years ago, grew up, developed significantly with the different technologies, and will eventually die. Our species lived for a hundred thousand years without writing; this did not prevent us from developing symbolic thoughts, mythologies, religions, social organizations, artistic activities, and so on. Writing appeared in Mesopotamia for producing administrative or accounting documents. It developed considerably after the invention of the printing press and exploded in recent decades with digital technology. But it is these same digital technologies that will lead to its disappearance. Today, the keyboard reigns, young generations no longer write by hand, and the development of generative AI tools means we can already dialog with machines without typing text. We are witnessing the programmed end of writing, but to quote Ad Reinhardt, the end of writing is not the end! (laughs) There will be other ways to communicate among humans that will emerge.And certainly, writing will be studied by a limited number of people, much like how we study a dead language today! In the piece U.T.O.P.I.A, each letter of the words transformed itself in a geometric shape, which is dynamically blurred, and generates multiple traces, leading to a global impression that the word UTOPIA is melting. Such work questions the future of writing and echoes to its own downfall.

What for you is inspiring about William S. Burroughs and his famous cut-up technique, and how it has influenced your work in general?

The Cut-Up techniques developed by William Burroughs in the late 50s and 60s opened new horizons for me. Burroughs was a writer, but when compared with other Beat artists, he has a very peculiar and singular visual approach to words and language. His vision was also political: How to fight against language? How to cut the printed page so that words can be liberated, how to cut the present to let the future come? Cutting up a linear text at random into different parts and reassembling them into a new unpredictable and illogical “text” is not so far from what I have been doing with algorithms and computers. I am not using digital technology to celebrate it. I use it as an aesthetic tool, with a critical approach not so different from Burroughs’s own use of the chance factor in his writings. The cumulative effect of control on the one hand and the rejection/denial of control on the other yield, passively, to the liberation of a new language. This is exactly what I do: by introducing the random factor in language, a new language emerges in confrontation with the control structures of the surrounding societies. To me, Burroughs’ texts are a perfect echo to our era. When it started to become popular, the Internet was hailed as a unique opportunity to change the world. Nowadays, it tends to appear as a gigantic mass surveillance infrastructure by which we are all controlled and under close scrutiny. The early utopian perspective has morphed into a control system as depicted by William Burroughs in his fiction.

There is the three-metre-long wall installation, THE END OF ART IS NOT THE END? in the Bluerider Show. What does this statement pertain to?

The idea of the "end of”, especially “the end of art”, is not new, it has been around for a while. The first one to address it was a French painter, Paul Delaroche. When he saw the first photographs, he immediately got worried about the competition they posed to painting and declared: "From today, painting is dead." This was in 1839, almost two centuries ago. He was both wrong and right. He was wrong because photography did not kill painting, on the other hand it made it free, and let all the modernist adventures happen, from Manet, Picasso, Mondrian, Pollock … But Delaroche was right in the fact the painting from his time, became dead. Since that time, the subject of “the end of art” has continually resurfaced in the practice and history of art. I also think of Alexander Rodchenko, with his famous monochrome triptych in 1922, "the death of painting," who declared, "it's all over." In the print installation “The End Of Art Is Not The End”, the wall is entirely covered by 20,000 images, all of them are the outcome of google searches on keywords "the ends of ...". From this visual database, I assemble and interlace the images next to each other as well as above each other, obtaining ablurry and organic texture. Individual image nature can be revealed/read when using a lenticular sheet that the visitor can handle and apply onto the wall. The work deals with how we see images today. For me, the whole paradigm of our relationship with images has changed, more and more of images are produced every day, billions of them, all uploaded on the social media platforms. However, less and less are really seen by mankind, while all of them are deciphered, analyzed and processed by machines and AI.

THE END OF ART IS NOT THE END is at Bluerider Art, Mayfair until August 25. Find out more here