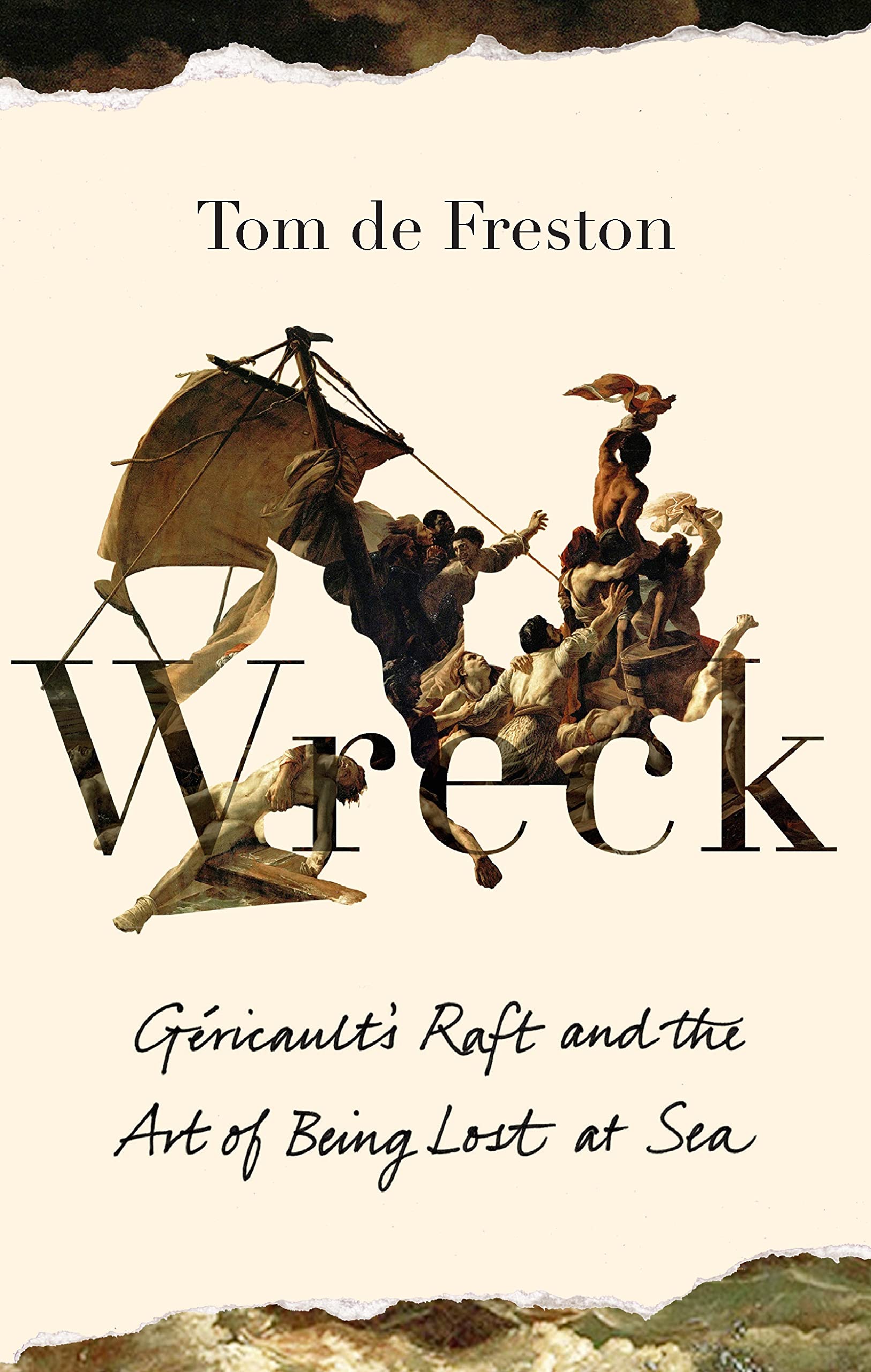

There are some projects in life that continue to evolve until they become simply monolithic in both scale and ambition, and the artist Tom de Freston’s latest visceral explosion of expression is one such undertaking. Literally born from the ashes of disaster when his studio burned to the ground, along with twelve years worth of work, it consists of his recently published and critically acclaimed book Wreck, which melds memoir, fiction and art history in a deeply personal exploration of Gericault’s The Raft of the Medusa, a series of emotionally excoriating large-scale paintings (currently on show at gallery No20), and a documentary film that deep dives into the collaboration he was engaged in at the time of the fire with Professor Ali Souliman – a Syrian intellectual blinded in a bomb blast in the 90s, who muses on the nature of trauma via interaction with de Freston’s artworks. Suffice to say, it’s a truly stunning body of work. Here, the artist talks to Culture Collective about overcoming despair, exploring psychological hinterlands, and reaching into the dark heart of truly great art.

What was the genesis of your fascination with the painting The Raft of the Medusa?

I first encountered Gericault’s The Raft of the Medusa during the final year of my fine art degree. I was very lost, making pretentious and self-indulgent abstract paintings inspired by the internal geometry of Piero della Francesca’s Baptism of Christ and the internal light of Rembrandt’s late self-portraits. We went on a field trip to Paris and I found The Louvre an alienating place, nothing spoke to me until I saw The Raft of the Medusa. There was something in its sheer scale that pulled me in magnetically, but it was beyond just size. There was also something of the mechanics of the painting – the way the cast of characters are arranged, corpses larger than life which threatened the very frame of the picture, as if they might spill out and onto the museum floor at any moment. And there was a sense of that movement working in both directions, as if it was a painting that pulls you in, and places you in the centre of its dark heart. It was such a profound experience. I knew in that moment that this was what I wanted my work to do – I knew I wanted to make paintings that you might inhabit; that would invite you to enter psychological hinterlands.

How does your book Wreck explore your feelings about the painting in regard to your relationship with your father?

My father died in 2013, and nine years later, it is still something I am processing in some ways. After his death the pain in Gericault’s painting caught my attention in new ways. One of the things I wanted to do in Wreck was to talk as openly and honestly about the connections between personal grief and trauma and the art I make. I wanted to pull the curtain back, to use language as a way to excavate the psyche, to be as vulnerable as possible. But I didn’t have any desire to write a misery memoir. I wanted to grapple with how these pasts and relationships can be full of ambivalent feelings, and how trauma can erase memories. I wanted to point towards the unknown as much as the known, and go to those spaces of mysteries, uncertainties and doubts. I wanted to fight the lie of neatness and certainty.

Talk to me about the genesis of your collaboration with Professor Ali Souleman and filmmaker Mark Jones. How does the collaboration work?

Ali, Mark and I actually first met through a mutual friend and collaborator. Simon (a writer and Professor of Shakespeare at Oxford University) and I had been working on a project focused on the character of Poor Tom from King Lear, and more broadly on the ways in which the play seemed to resonate with the Syrian conflict. Ali lost his sight to a bomb blast in Damascus on New Years Eve 1996, and had recently moved to Oxford from Damascus, where he had been a Professor Dramatic Arts, and had often taught King Lear, drawing parallels to what was happening in Syria. We started exploring the idea of collaboration but for various reasons we put it on ice. But a friendship was formed. A few months later Ali asked to visit my studio and we spent a few afternoons exploring my paintings through touch and description. There was a particular painting that struck a chord with him, and seemed to somehow resonate with some of his experience. It was in that moment that the genesis of the project was formed. Might we be able to translate Ali’s rich internal world of memory and metaphor into a body of artwork? To make the unseen, seen?

Did you experience a state close to despair regarding the fire that destroyed those paintings in your studio?

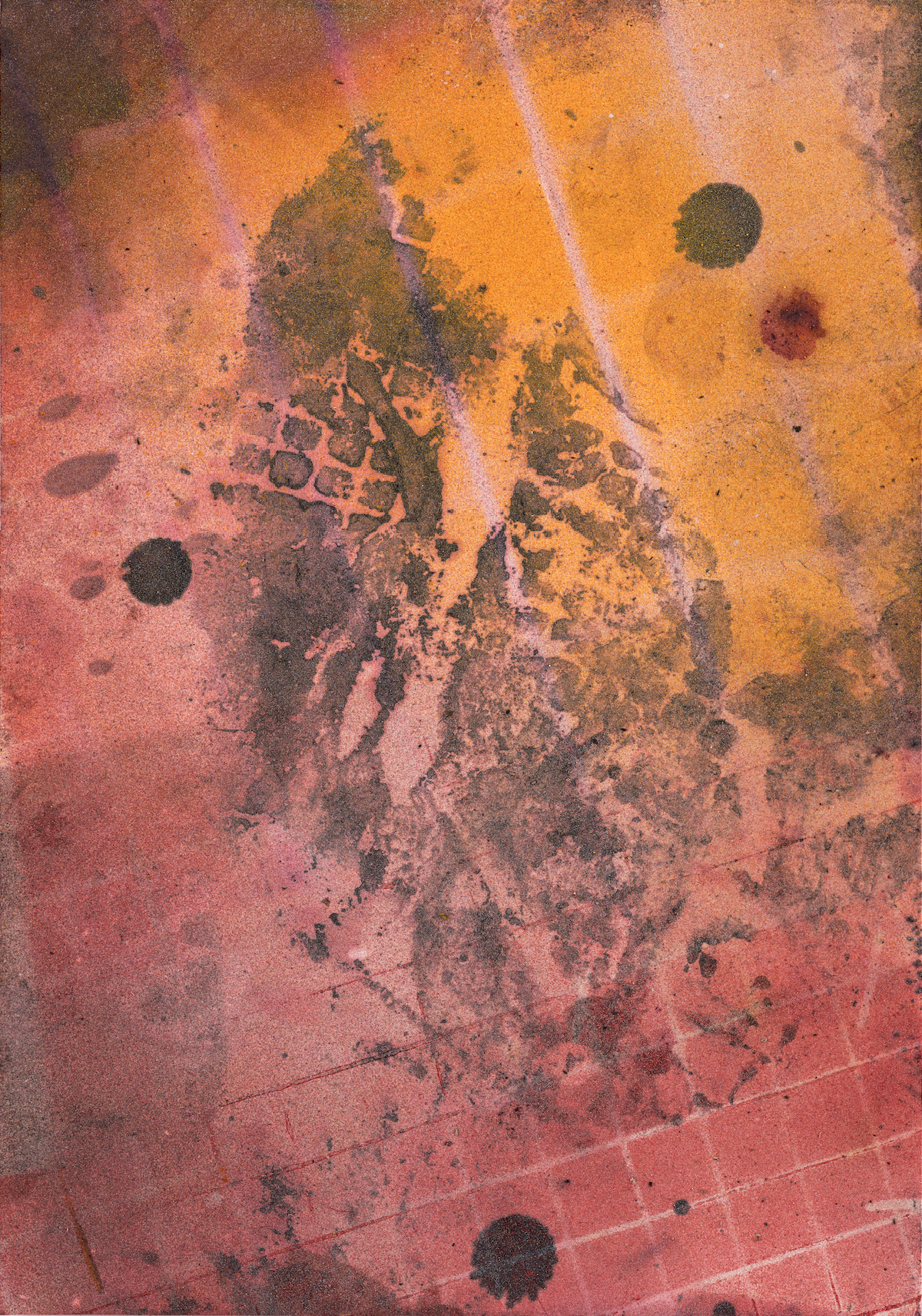

In the days after the fire I sorted through the burnt out husk, trudging through two feet of black, thick, smoke filled water and sludge. This stinking skeleton of a building, full of the burnt remains of twelve years worth of work was terrifyingly and hauntingly like an unturned version of the raft, emptied of it’s cast. When the fire in my studio happened, I was putting the finishing touches to result of my collaboration with Ali Souleman and Mark – and I was using a blow torch when it got out of hand. Within minutes the entire studio was engulfed in flames. Everything inside was gone. The morning after, when I was inevitably still in deep shock, I felt this clarity of vision. I knew, instantly, that whilst it was a devastating end of so many things, whole worlds of work made, it had to be, if I was to survive, a starting point as well. I think I knew, even then, that I would make work from the burnt remains. That I would salvage all the burnt materials I could, that they would become something, somehow.

How did your collaborators react to the fire?

After years of working on this project together, we now had this burnt out husk. It was so unnerving when we walked around the space together because it was as if the safe divide between art and reality had crashed. Stood in the space we all mused on how hard it was to place ourselves. Were we inside a work of art, a mirror of life or merely a scene of destruction, with its uncanny and disturbing visual resonance with the very horrors Ali had lived through in Syria. The studio and the remains of work left looked like drone shots across Aleppo. It was clear that there was only one option, to respond creatively. Otherwise, we would be left in this space of pure despair.

What did you do next?

Two days after the fire I called Mark and I said there was something I needed to film, but I didn’t know why, or to what end. He filmed me for a few hours as I stripped down, turned burnt walls into small stages, covered myself into the damp, smoke filled piles of insulation material and worked my way through a series of poses, each one involving me gathering up, moving, peering through or burying myself under the debris and rubble of the studio and the burnt remains. It was an act of mourning, a ritualised letting go.

What do the paintings you have worked on since the fire represent in terms of your evolution as an artist?

I think the paintings that have come following the fire, that are on display in From Darkness at No20 arts represent a significant evolution in my work. I think the noise of violence and horror has been replaced by a desire for beauty and for a wide spectrum of emotions. In the studio at the moment there has been a sudden and utterly unexpected flourishing of colour, and whole new expressive language of painting, as if the work has been liberated from previous constraints and self-imposed expectations. There is no clear project, no clear program, nor preconceived justification. It is as if I am finally making the work I have been wanting to make for the whole of my life.

From Darkness exhibits until June 18th at No20.

Wreck is available in all good bookstores.

You can find out more about Tom de Freston here.