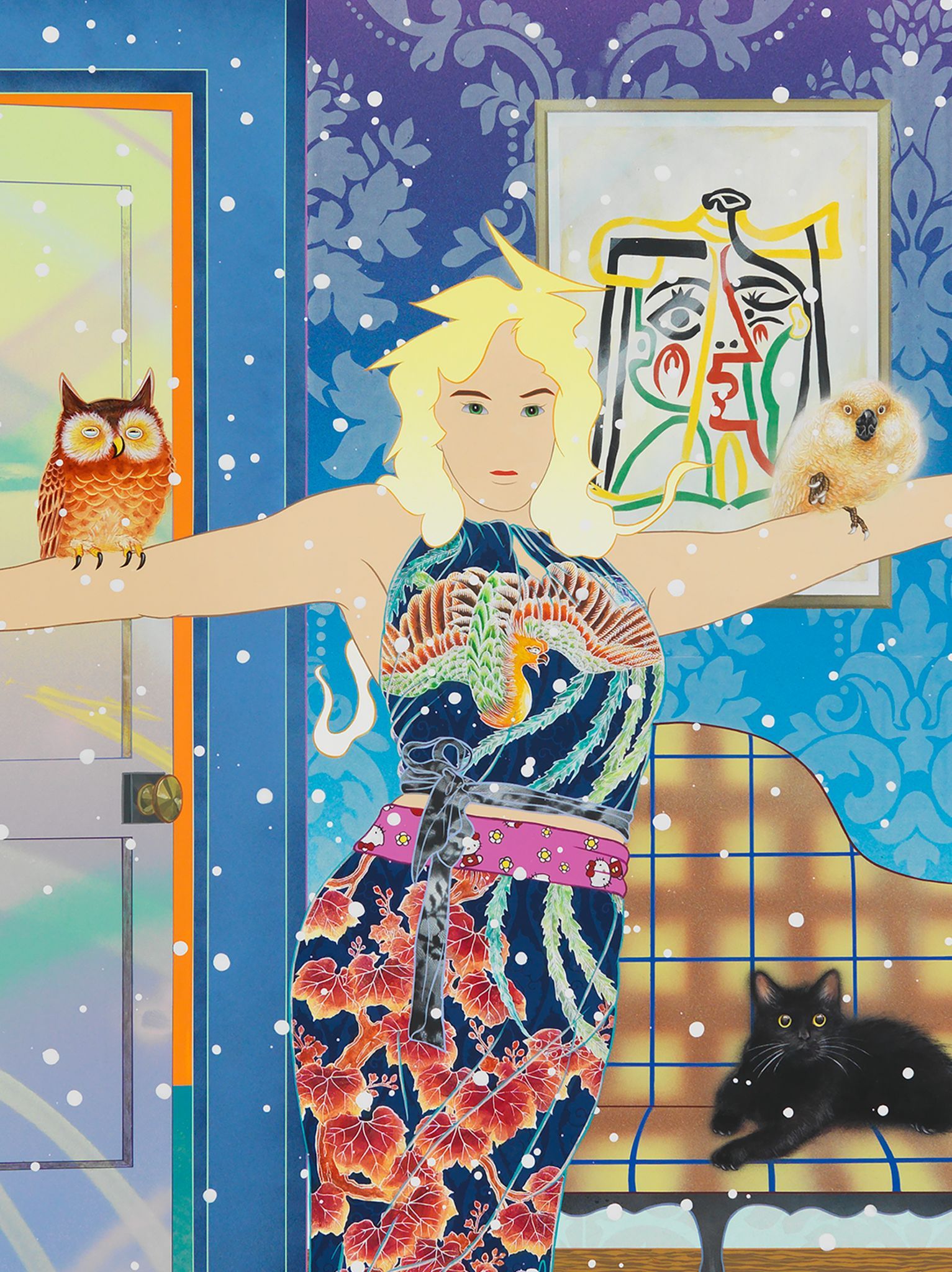

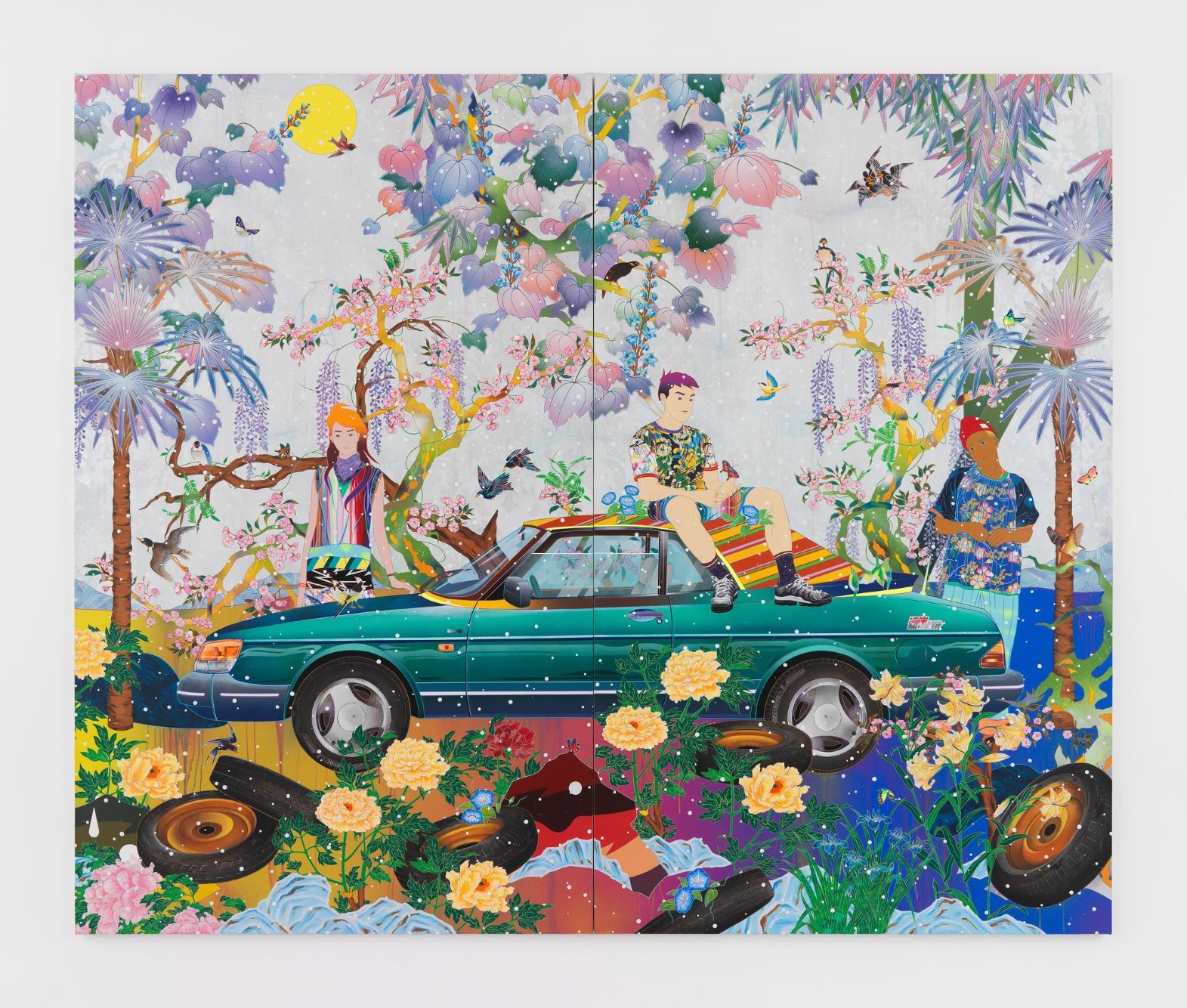

We live in the era of the art-directed reality, where the instant appropriation of a veritable smorgasbord of cultural signifiers is readily available in how we present our identity to the world via the smartphone – absorbing everything from pop, to baroque, to ultra-glamour, to, well, whatever, at a vastly accelerated rate, flattening cultural hierarchies as we patch together our unique digital exquisite corpses. And it precisely this paradigm that Tomokazu Matsuyama is currently exploring in his show Episodes Far From Home at Almine Rech – incorporating highbrow and lowbrow motifs from East and West in a visual language that not only references the New Yorker’s own trajectory as a global citizen, but also the post-postmodern condition we all find ourselves in, in which we seemingly have access to everything, everywhere, all at once. Matsuyama’s bright, bold and overwhelming sculptures and paintings exist in a timeless visual autonomous zone that singularly refuses to be cornered into any one narrative reading, being designed to plunge the viewer into a universe of ambiguity – a maze in which we are invited to map our own sense of self, beyond reductive readings of race and culture. As such, the artist invites us to view not only the world in all of its vast complexity, but also to ask ourselves who we are, and who we want to be, in this hyper-modern moment of the global citizen – where the concept of somebody living in a specific country, and having their identity tied to one cultural construct, is all but obliterated in oversized canvases and sculptural works of overwhelming beauty, where the detritus of consumerism can be found amongst dense oriental flora and fauna, or the wallpaper of William Morris feels as though if could grace the interior of Virgin Galactic. Here, the artist talks to Culture Collective about creating art as a question mark, the inherent reality in faking it, and explains why whatever you see in his work is simply the outcome of your own cultural conditioning.

This work feels like a comment on the art directed realities of social media – what would you say you are trying to achieve in this latest series?

If you look at art history, it has always nurtured the desire to be innovative and advanced in a non-linguistic way, right? Because as an artist, you want to find a way to connect the world we live in now, and also find connection within the past, in the hope that you can then connect to the future. In order for me to make those kinds of connections now as an analogue painter in a digital world, it was obvious to me to reference social media, because that has a huge impact and influence on our current lifestyle. It is giving us lots of ways we can idealise ourselves – glamorise ourselves, or edit ourselves into a romantic or luxurious setting. And if you look back into a lot of European portraiture, then they were doing exactly the same thing. Except, at that time, you would stage yourself in your idealised setting, and then you would hire an expensive painter, and these edited stories that would then be painted became significant cultural signifiers. But now, everybody's allowed to do that. We don't need to hire a painter any more, because all we need is a smartphone. And I find that pretty interesting – this idea that to make yourself into an icon was once very costly, and only allowed for the elite, but now absolutely anybody can do it, and anybody can create their own narrative. But, at the same time, we're forging these identities through our phones – we are faking our identities, but the act of faking itself is a reality.

Are you are exploring this sense of the ‘fake but real’ by bringing together ephemera and motifs from so many different cultures?

Throughout history, younger artists were always trying to become innovative in being realistic – trying to be honest, trying to paint content that was not allowed in the art world. And they always changed the game by broadening the idea of art. My interest is kind of about that, too. In my work, you see influences from Japanese subcultures, and lots of traditional European cultures, such as oriental patterning, fashion, architectural formalities, ornamental decoration, William Morris, Dior, and so on … And you’ll also see a painting of something like a packet of Lays potato chips, which graphically represents a conservative cultural symbolism that we don't generally feel is relevant to what we see in the art museums. But what's bad about having have Pringles or Cheetos as painted matter, and them being in MoMA, or being in the British Museum? If you repaint these things within the canvas, then all of a sudden a packet of Lays doesn’t represent just a packet of Lays, or our consumer culture. It talks about our contemporary life. And I don't want to exaggerate them in a Pop or Warhol way by saying I'm bringing these items that are not supposed to be in what's so called art, or trying to say something very unique about consumerism. I just want to bring more daily life, and more daily reality into the paintings.

I like that sense of flattening hierarchies for the sake of it – the blending of these different elements is not intended as any kind of overt cultural statement, then?

As a painter, I do not want to deliver any very strong statement. And that is for a few reasons, but mainly because you can only understand what you know about meaning in life, from your own background. That means that when you see my paintings, you're starting to make sense of them, firstly out of what you know, which is based on your own culture of attribution, and then you’re going to start to react mostly to something in there that you don't understand, or something that feels distanced from you – and that could be an Asian influence, or that could be Japanese, or even a more broad term like Oriental. And as a viewer you are naturally going to try to make a story out of the painting, but you're only making a story based on what you know and what you bring to the painting. As such, the meaning of the painting becomes a reflection of who you are – and that's exactly the open narrative that I always want to create. I never want to say, this is what I'm trying to tell you in the painting.

There seems also to be an explicit sense of presenting something new – a character that is bound by no cultural tropes …

When we spoke before, we discussed that, of course, there's a lot in there about being a minority, and it is a great thing that minorities are being able to amplify their voices through art so much more now. However, in some ways, I think that's also almost a little bit over these days. In America, we did live through BLM, which was a great thing, because we needed that spotlight, and we needed that spotlight on Asian hate, too. But I think humanity is not necessarily about talking about the equableness of ethnicity, or the colour of our skins, or race, you know? If you look at the bigger picture, we're all humans, right? So in order for me to talk about the future, and look at the past, I didn't want to overly talk about me being Japanese, me being Asian … Instead, I want to bring a strong sense of this moment of global diversity, all being mixed together. So, in the work, I'm never talking about decorative versus conceptual art; I'm never talking about modernism against traditionalism, you know? I’m just asking what would happen if all of these things are placed in the grey zone, so it's all open for interpretation and you, the viewer, are asked to make sense out of it. I always want my art to be a great questioner rather than a huge, bold statement.

Do you think we are evolving towards a new culturally borderless sense of identity?

Well, it's the most glamorous, interesting time right now to talk about our global identity, with all this digital information being abundant and fluid, giving us accessibility to any type of immersion that we might want to explore or use to influence each other. And that is great, because rather than pigeonholing your own singular identity, this new access to reminds us all that we do all live in the same world. That’s why, when asked about my work, I always say it's not about East and West. It's really about both. I have my very strong Eastern identity, sure, but I'm creating work heavily based on western ideas, so they merge into one space that I want people to find both timeless and timely. That's the important thing to me. The whole idea when I create work is that I want to feel the sense of a universe. I want the painting to be something that is non-cultural, and non-religious, with this sense that it's also very now, and also that it is fun, and contains hope. And that hope element is in there because I do have this Asian DNA, and, historically, what we make in the Asian traditions is always for hope and luck. Buddha statues are placed to scare away sickness, or when we paint little coy going up the waterfall, what that represents is that once it goes up the waterfall, it becomes a dragon – so, it represents future success. There's always this lovely hope factor. Can a fortune cookie become an artwork? I think so.

Episodes Far From Home exhibits at Almine Rech until May 20

Images (top to bottom): The Letter Half Awake (detail), 2023, acrylic and mixed media on canvas. By And By Daylight (detail), 2023, acrylic and mixed media on canvas. Winter Song Solitudes (detail), 2023, acrylic and mixed media on canvas. By And By Daylight, 2023, acrylic and mixed media on canvas. All images courtesy of the artist and Almine Rech. Art Photography: Melissa Castro Duarte