The French photographer and director Michel Haddi has one of the most impressive portfolios of any living contemporary portrait photographer, having shot the likes of Johnny Depp and Kate Moss in the nascent stages of their careers, and legends such as David Bowie and Debbie Harry at the height of their fame, not to mention Faye Dunaway, Angelina Jolie, Gigi Hadid, Uma Thurman ... the list goes on. The fact that he carved a career shooting for some of the most prestigious fashion magazines on the planet is all the more impressive when you consider his tempestuous upbringing. Born in the infamous Paris rue d'Assas to a French soldier, whom he never knew, and an Algerian Muslim mother, Hadid spent his formative years ricocheting from one foster home to the next, before being entered into the Sisters of Saint Vincent de Paul Orphanage in Paris at the tender age of six. It was there that he developed a fervent interest in the copies of Vogue that his mother would bring for him – a magazine he would later go on to work for for over a decade, while also shooting for Vanity Fair, Tatler, Rolling Stone, Interview, and The Sunday Times, to namecheck just a handful. Over the recent pandemic, the photographer, who is widely celebrated for the intimacy he brings to his portraiture, turned his gaze inward, and the lens of his camera settled upon the beauty of the flowers in the home he shares with his wife. The profoundly sensual results of this undertaking have now been brought together in his latest book The Legend: Flore De Mal, which invites us to look at flowers as living, sexual organisms that can provide a mirror to some of our deepest desires. In this rare interview with Culture Collective, the exemplary image-maker candidly discusses the eroticism at the beating heart of his latest collection, and tells us why true beauty always contains the frisson of danger.

What made you create this series of photographs, and what are you trying to communicate in the eroticism you imbue these flowers with?

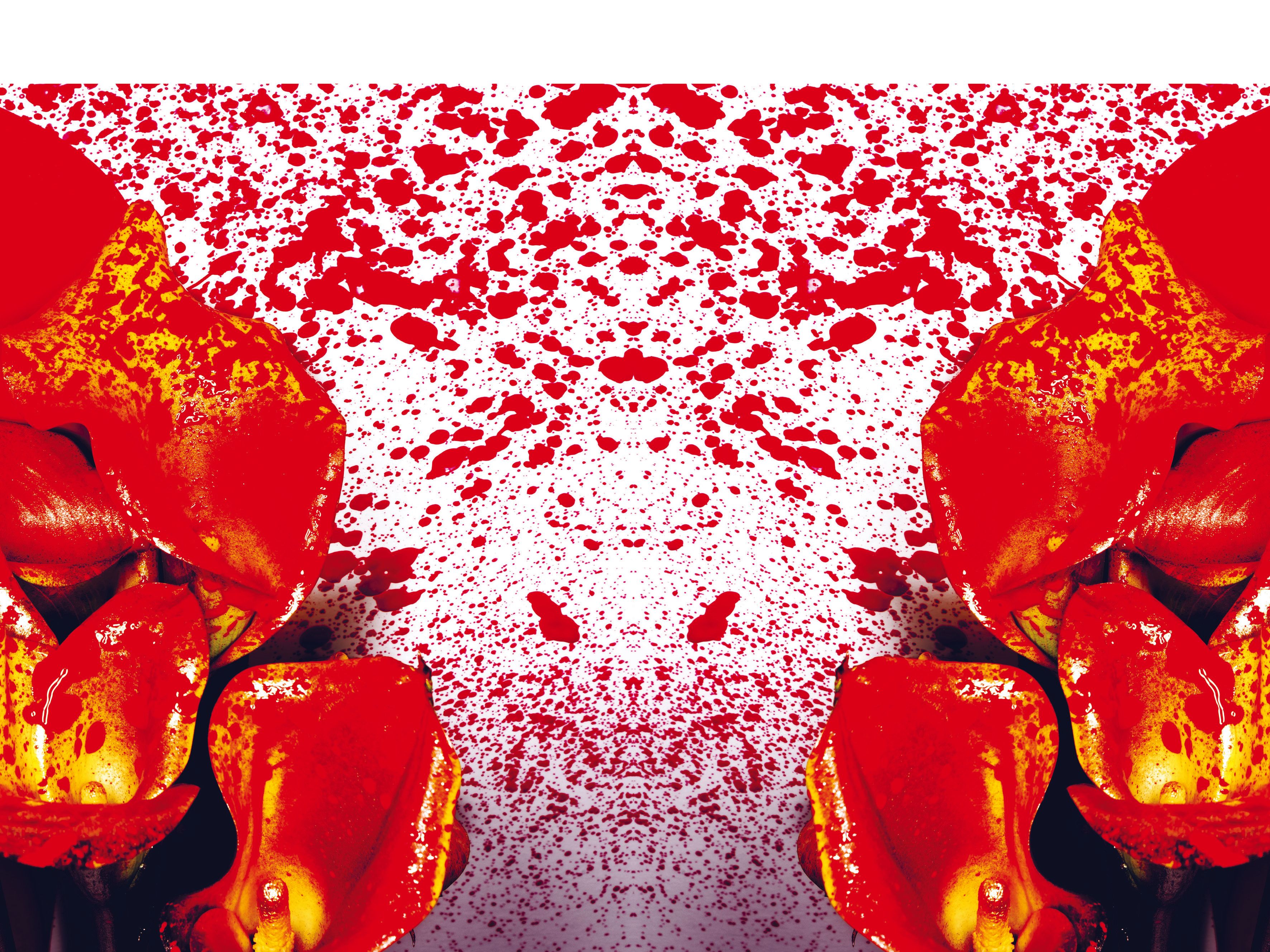

I love the eroticism of flowers, and I have always loved Georgia O’Keefe and what she did with her paintings of flowers, which are almost pornographic. What I am really trying to create with my flowers is a similar erotic fantasy. I began work on them in the pandemic, because everything was shut down, and had this desire to really go deep into the flowers. I wanted to create a kind of theatre of the soul with them, because I have always associated flowers with blood and sex. I wanted them to have this very viscous, sexual quality, so my flowers are dipped in a kind of plastic and then when they dry it gives them these strange shapes, and this psychedelic quality you often see in things when you take LSD. There is this sense the images have of exploring blood and psyche and sex, and they almost show pornography without showing pornography. I believe that the erotic is a big part of our life. We are very drawn to sex and blood, because blood is a living form and sex is about life-giving and procreation, and then, of course, the flip of both those drives is death.

Why have you chosen to reference the French poet Baudelaire in the the book – what inspires you about his collection of poems Les Fleurs Du Mal?

I wanted to reference Les Fleurs Du Mal by Baudelaire, because I love the way during that period that he and other poets used flowers as a metaphor to get past very strong censorship. And when you read the poetry of Baudelaire there is always the sense that there is a double meaning – in a sense, he says that in all of our relationships with men or women, there is always the bright side of a coin, but, at the same time, there is the evil dark side of our nature that has to be considered too. And it’s a dark side that we all have, you know? I mean how often is it in society that we tell stories of people who have killed the thing they love most? My hope when people encounter my flowers is that maybe they're going to be a little bit disturbed by the imagery, and that they are going to find something very beautiful, but also realise that there is something odd about those flowers, and a little dark and shadowy. I want people to think about themselves when they see them, and think about their own life, and the fact that they are a living human being. It’s a reminder that people should look at whatever is around them much more closely – we are only a mirror of what is already there in nature.

How do you conceive of beauty and how does that play out in these works?

Beauty goes with the soul, and there is often a shadow side to beauty. For example, I don't remember the name of the specific flowers, but there are many flowers that are so very beautiful but also poisonous, and deadly to human beings. I'm a Buddhist, and as a buddhist I try to see everything around me with the eyes of a child, and I believe that when you are unable to do that, the soul dies. I'm very respectful of everything around me, like the flowers and the trees, and so forth, because I realise I am also just a part of it, you know? I studied martial arts, and I always recall this quote from Bruce Lee – that I will paraphrase – but he said, instead of looking at your little finger, why don't you look at all the glory of everything around you? When I photograph flowers, I try to do that, and communicate that sense. I have no interest in photographing flowers in a traditional sense. I'm looking at the flowers as a living organism, and asking people to look at them again and more closely – I am looking at the flower as if it could talk to me, and teach me something.

In a way, would you say that you are applying the way you would shoot a human being to how you shoot these flowers …

Thank you. Yes. That is exactly what it is. I mean, I have photographed huge directors, models and actors, or, let’s say, a white tiger centimetres from my face, or snakes, or whatever, and each time the way I approach the image is exactly the same. I have a lot of empathy and a lot of love for all of my subjects, and I'm careful to send a message that I absolutely love them. For me, there is no difference, really – they are all shapes and forms. If I see big flowers from five metres away, for example, then, okay, I'm going to see that maybe it's a flower, but I'm also first going to see the shape, and the shape might look like the shape of a woman or a man, so, in the way that I shoot them, you are going to see some kind of thread that relates to all of my work. Whether it’s a flower, or a woman or an animal I am shooting, it’s always going to be about my way of seeing the world, and my way of transcending basic representation.

What would you say has changed or evolved in your practice since you first picked up a camera some 40 years ago?

Well, it's interesting because nothing has changed since the first day. Since I first picked up a camera I have been looking at things with big eyes, and when I work with people I always try to find something magical about them. It's not while I'm photographing the person that the photo happens – the photograph happens before in the human exchange when I meet someone. Take Faye Dunaway, for example, when I worked with Faye, I met her and said, for me, you look like a 1930s screen icon, how would it be if I dressed you like Marlon Dietrich? And she looked at me, and she said, okay. I just said something, or felt something very instinctive, when I met her, and that idea became the photograph. That instinct is primal, you know? It’s a condition that we all have, and to tap into that instinct is what I try to do. In terms of the flowers, I almost see them as a very very pure representation of what we are, without any adornment. Does that make sense? I mean they are primal – primal love, primal sex – and they don't lie. These flowers are very in your face, and they tell you exactly what they love, and what they want. They are very beautiful, and sexy, but they are also a reminder that some flowers can kill you too.

The Legend by Michel Haddi is available now

Buy the book and find out more about Michel Haddi here

The Milan based gallery 29 Arts in Progress and photographer Michel Haddi will present the second phase of his major retrospective exhibition Beyond Fashion from the 16th January to the 16th March.