Piers Secunda is a London based multi-media artist forwarding a research heavy practice that uncompromisingly delves into some of the most significant geopolitical subjects of our time, such as the bloody histories of so-called ideological conflicts and, perhaps most pertinently, the deliberate eradication of cultural iconography – with a particular lens upon the wanton destruction of culture that has happened under both the Taliban and ISIS. His most recent such undertaking has been somewhat closer to home, and looked into the hidden history of Alderney in the Channel Islands during WWII – the occupied site of an alleged German Concentration camp on British soil that has been conveniently airbrushed from the history books. Over three years, he conducted painstaking research into the remains of a firing squad wall on the island with the help of internationally respected forensics specialists in both the UK and US, including ballistics experts from John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City. In this rare interview with Culture Collective, the artist tells us why he feels an emotional responsibility to devote his practice to unearthing hidden histories, and explains why the brutal obliteration of culture is the bitterest of pills for any artist to swallow.

Would you say you are a politically motivated creature before you are an artist?

I’m definitely emotionally motivated before anything else. I used to make colourful abstract assemblages years ago, when I was living in New York, but then 9/11 happened and that was a total game-changer for me. I realised there and then on a fundamental level that, for me, art has to do more than look good, and that there is a space for art to have compelling social role in the world. The thing that preceded 9/11 was the destruction of the Bamyan Buddhas by Al-Qaeda, and that shocked me to my core. I just couldn't understand why it had been done. I felt this sense of horror at the realisation that there were people who were willing to destroy the historic culture of a place wholesale, in order to flatten it and rebuild history. Of course, if you read the history of any place, you tend to find examples of this, but it was the first time it really hit me at a gut level, and I felt stunned, because I could not get my head around the idea that it was touted as a move to improve the lives of people from that place, which is what the Taliban stated at the time. It was a jagged pill to swallow as an artist, and when you go to places like the Kurdish region of Iraq, and you see towns and villages that have been completely flattened, it’s very difficult to remain impartial.

You are travelling to Iraq again soon to install two new works at the invitation of the government, can you tell us what you will be doing there?

I’m going to Iraq deliver a piece of mine to the National Museum in Baghdad, and I am going for a conference at the Mosul museum, which is all about the museum putting on a show that focuses on the damage wrought by ISIS and its on-going reconstruction – we’ll be looking at how well that has gone, and how they will project into the future having experienced what they have. One of the biggest libraries in the Middle East was in Mosul, and was burnt to the ground. I want to see what remains of the material there. I was actually first invited by the Iraqi government back in 2017, and I was given permission to make moulds of anything I wanted to, which, for me, was the broken stone elements of the sculptures that remained in the building. That body of work is still on permanent display at the Ashmolean – a reproduction of Syrian relief, which is two panels of the same image, one reconstructed, and one that is damaged.

Is it your intention in uncovering these hidden or lesser know elements of recent history to wake people up to the myriad evils happening in the world?

It isn't so much about awakening people, because when people are so absorbed in the way of life they live, they will never attempt to put themselves in the mind-frame of someone who does something like that. The intention in making work, for me, is first of all an attempt to document it, and, secondly, to understand what drives people. I do feel that I can now say with some certainty that the destruction of culture doesn't need to happen, and that it happens chiefly because of a failure of education. I think if we had a system of education where you are taught to think, present your own ideas, and then defend them, then the blind ideological destruction of culture that the likes of ISIS have carried out, and still continue to carry out in Syria and North Africa, would not happen. And we know why these kinds of groups arise. You can trace ISIS back to the creation of the nation state of Iraq and the Red Line Agreement. These experiments in injecting democracy into places that have of thousands of years of history in which democracy does not factor tend to go very badly wrong.

Recently, you trained your lens on the occupation of the Channel Islands in WWII and the alleged existence of a concentration camp on Alderney – what drew you to that story?

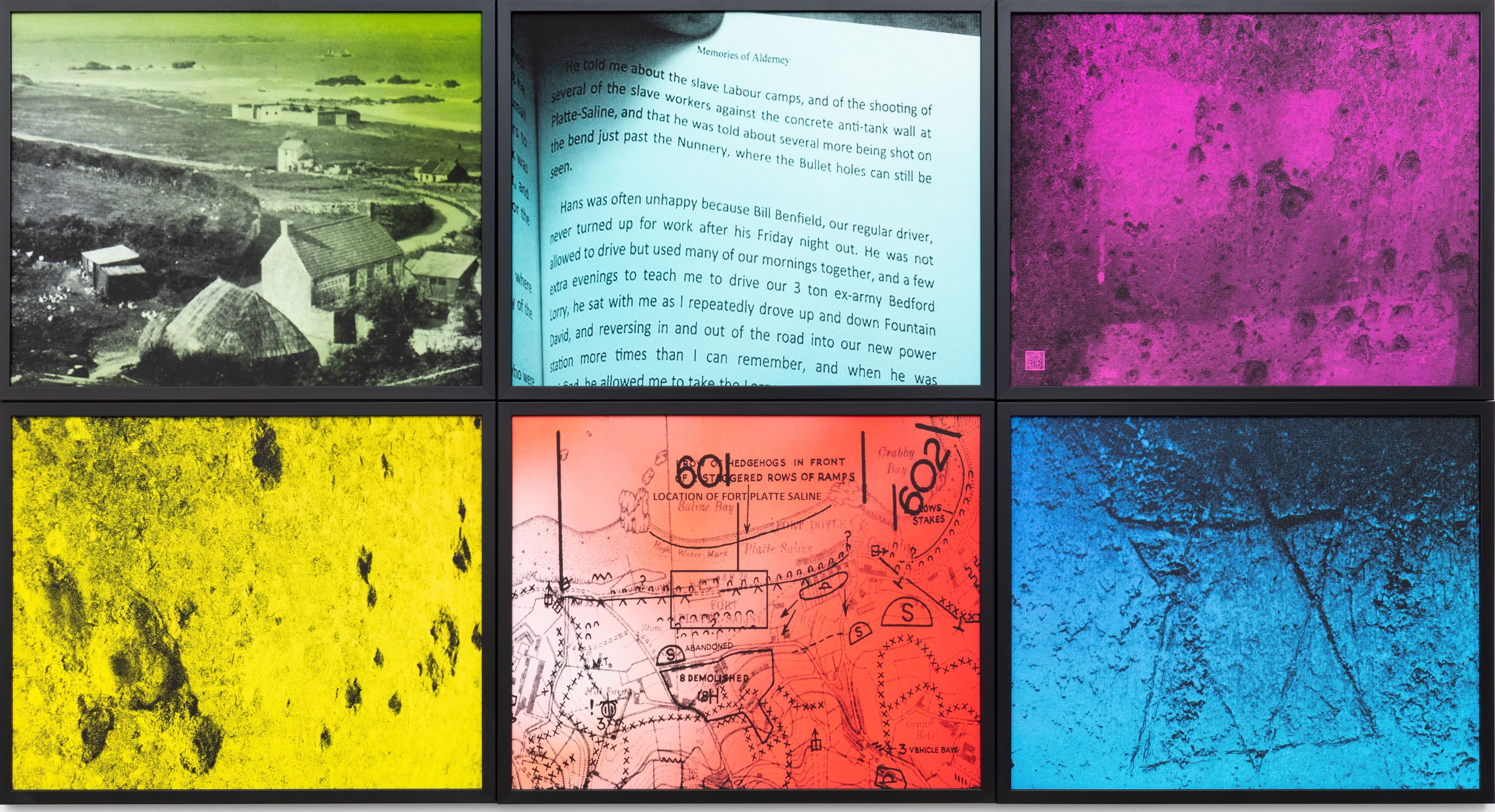

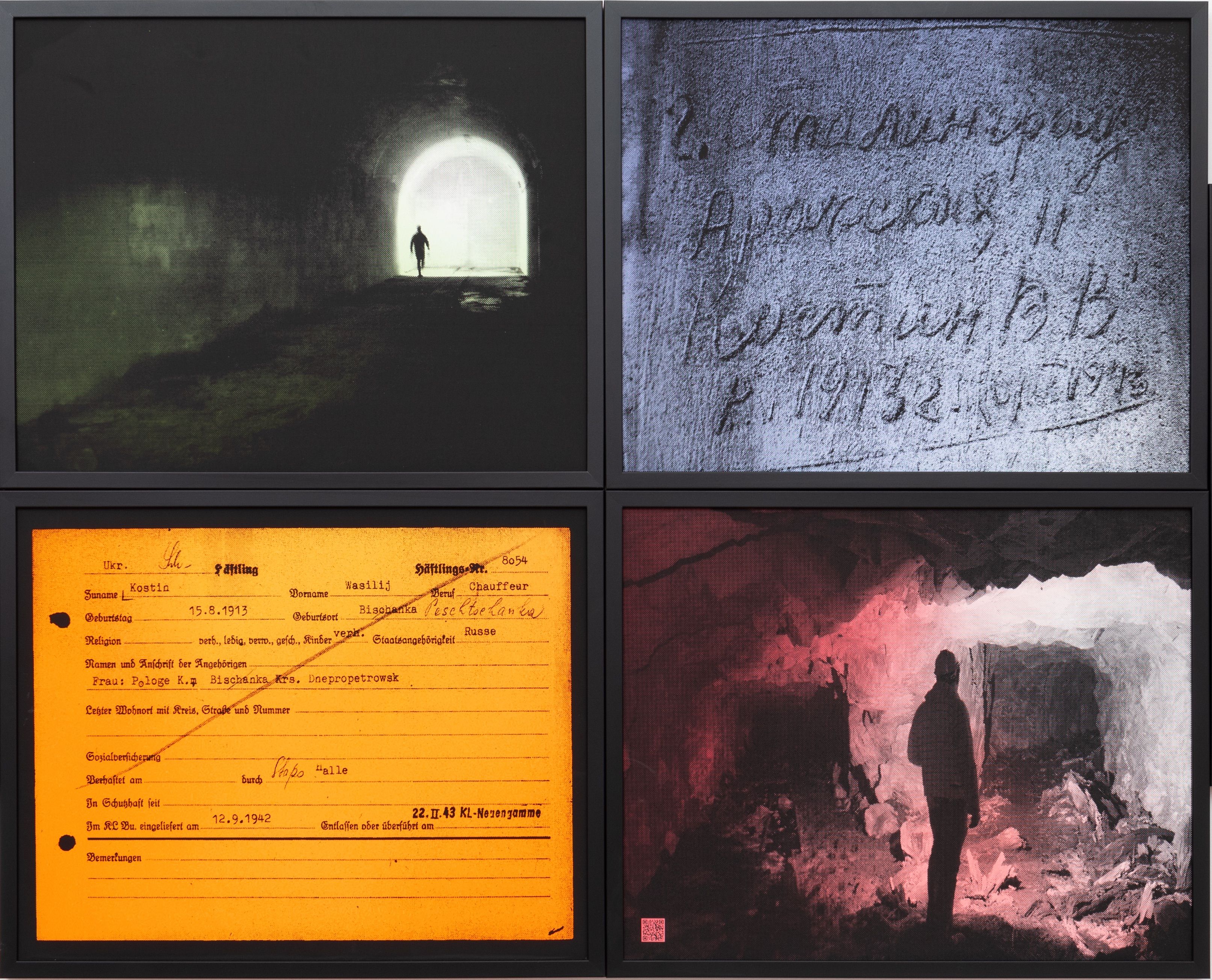

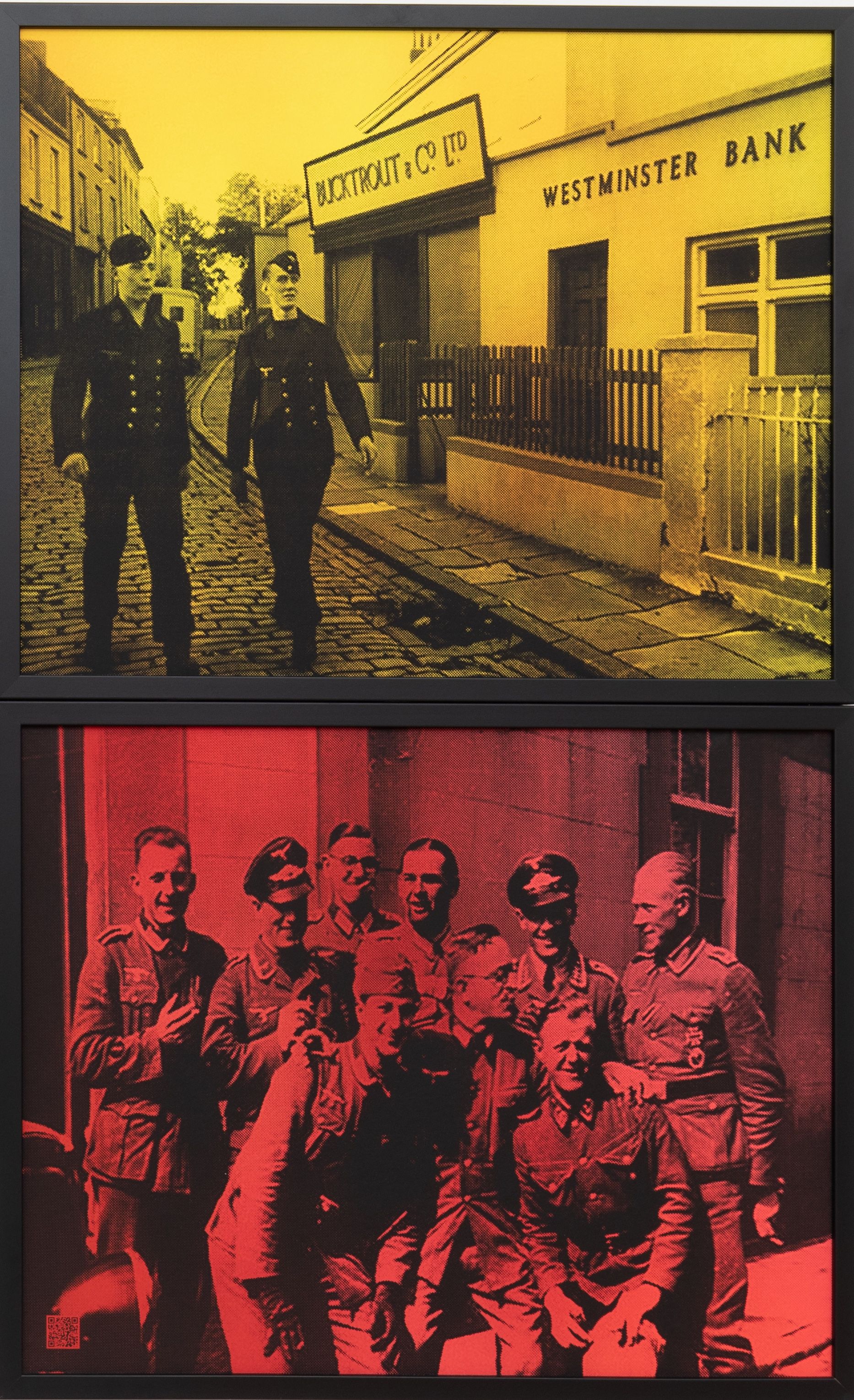

Yes. I was researching that for nearly four years. There have, of course, been many books about the Nazi occupation of the Channel Islands, but all of the works in my series are about the procurement of new material related to the story, and the exhibition recreated a section of a firing squad execution wall, which I was shown on Alderney. I had two main drivers in the Alderney work, one was that my father’s family, going back, were orthodox Jews, who used to live in what, at that time, was called the Greater Russian Empire (now modern day Latvia), and they left there for the UK. Also, my grandfather on my mother’s side of the family was an American pathfinder, so he would parachute into war-zones in WWII, and had actually been shot at by the guns on Alderney the night before D-Day. So, I suppose my drive to explore that history was personal. I intended to show to people that it can happen here, and, even more so, that it did happen here.

Do you fear that given propaganda and the bloody history of human conflict that we are doomed to repeat such horrors?

Yes absolutely. This re-moulding of history and culture is exactly what is happening now in Ukraine. Russia is absolutely tying to flatten the culture ito reconstruct it in their own image, which they also have done in Chechnya and Georgia, and, at one time, of course, across the entire Soviet Union. At this moment in time, the democracy that my grandfather fought for, and the soldiers around him on D-Day that were shot and killed for, are being eroded across the globe faster than ever before. This inevitably pushes our society further to the right, and there is no aggressive push back to slow that down right now because, as a society, we have become placated and complacent. The warring nature of human beings casts a very long shadow across our future, and I don’t know that that will ever be eradicated of softened. Hopefully, though, if we are sufficiently aware of the past – especially a past that has been swept under the carpet, then, we will have the option in the future to deviate from that path.

All images from Alderney: The Holocaust On British Soil, courtesy of the artist and Cromwell Place.

Find out more about Piers Secunda here