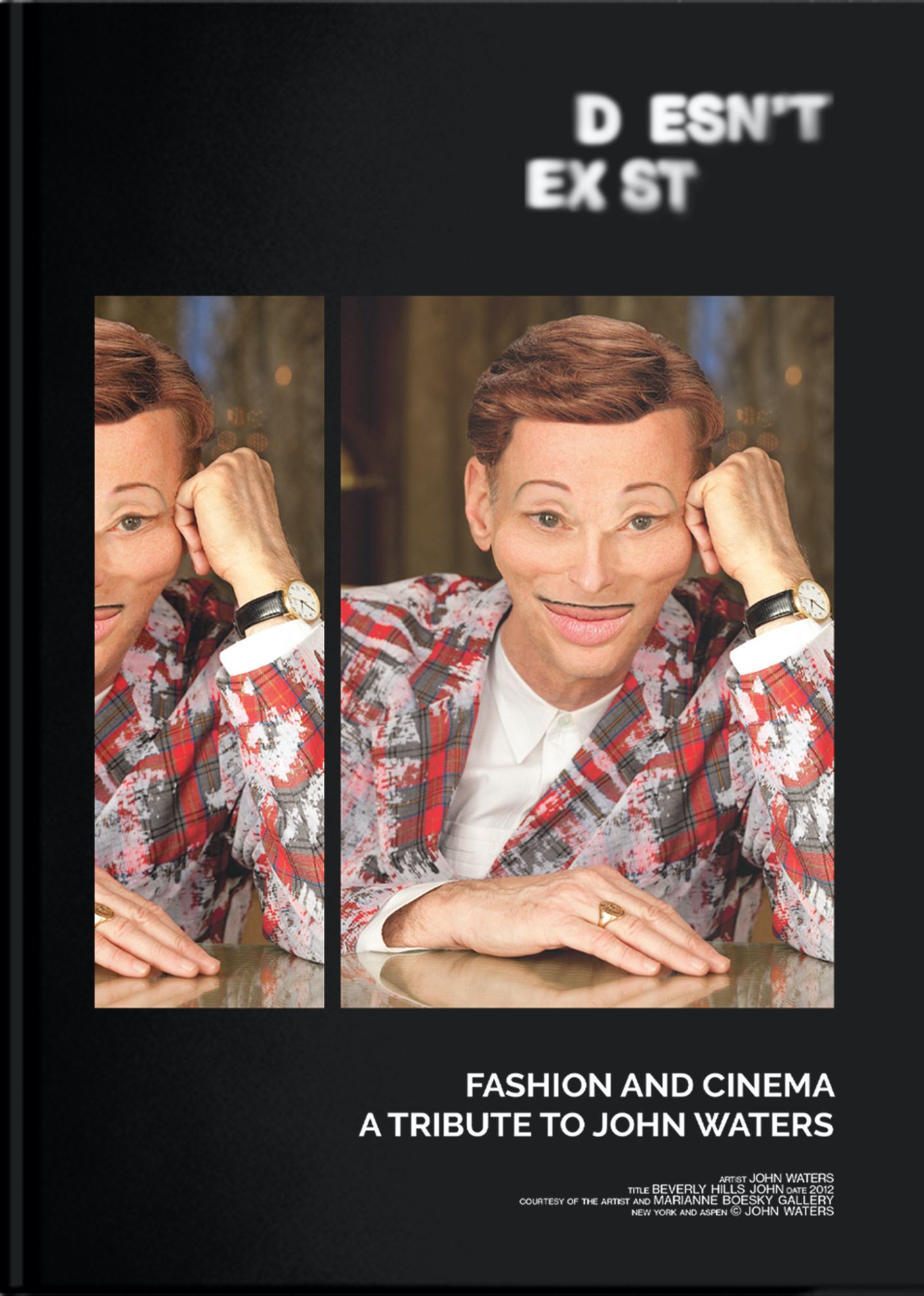

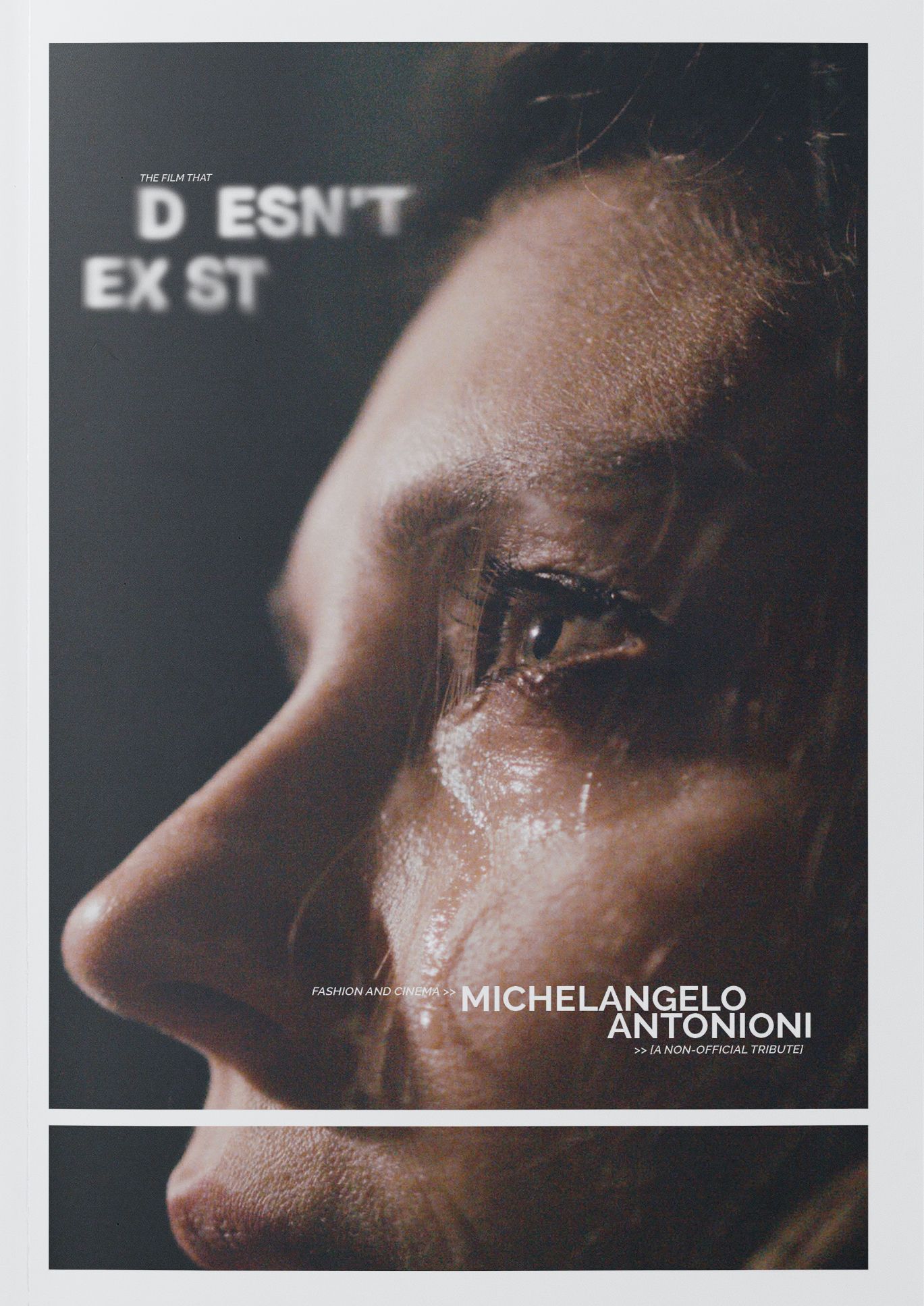

Doesn’t Exist is the brainchild of Saint Martins alumni Alex Babboni and comes in a hardback book format that pays tribute to some of the greatest filmmakers of our era via the lens of style and fashion. As such, each issue of the bookazine represents a limited-edition collectible art object, and copies are fast becoming hot property for cinephiles all over the globe. It takes one to know one, as the saying goes, and Babboni’s own passion for film is nothing short of obsessive. Originally hailing from Brazil, where he studied for a BA Cinema, his interest in the crossover impact of celluloid upon fashion, and vice versa, took root when he relocated to London to study at the London College of Fashion and Central Saint Martins, both of which he graduated from with with first-class honours. After gaining valuable experience assisting the former art director for Saint Laurent, he launched Doesn’t Exist magazine in 2019, as an homage to influential figures in both industries. The magazine kicked off with a paean to visionary Japanese fashion designer Rei Kawakubo, and has subsequently paid tribute to esteemed filmmakers such as Peter Greenaway, John Waters, Michelangelo Antonioni and Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. Here, the editor-in-chief of the inimitable new title takes House Collective Journal behind-the-scenes of a truly groundbreaking publishing venture.

Where does your fascination with film stem from?

I got into movies when I was a kid, starting with 'Xanadu' by Robert Greenwald, starring Olivia Newton-John and Gene Kelly. That was my first-ever theatre experience. The vibe and energy of being able to watch a film in a space like a theatre, I can say, acted like a magnet. When I was a teenager, my parents put me in charge of a video shop they bought. My job was to pick the movies we stocked. Two of the first movies included 'Black Rain' [1989] by Ridley Scott and 'Drowning by Numbers' [1988] by Peter Greenaway. Over time, the store became a cinematic treasure trove of films by directors like John Cassavetes, Fritz Lang, Mário Peixoto, Andrei Tarkovsky, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, and more. It was like a film lover's dream, to be able to access films from different genres and eras. Essentially, this experience served as a comprehensive and organic education into the world of cinema.

Where did the idea for Doesn't Exist Magazine come from and what is the ethos at its core ...

The idea might have come during my BA at Central Saint Martins. It all started when my tutor, Ian R Webb, pointed out how cinematic my images were. Fast forward over ten years, and I've nurtured this project into reality. The whole idea was to create a publication seamlessly blending the worlds of fashion and cinema, both deeply woven into my personal history. Bruce LaBruce nailed it when he described Doesn't Exist as 'a meditation on an artist', capturing the vibe of the magazine, which is a platform to shine a light on the intersections of film, fashion, and art, all coming together in a tribute to a standout figure in the fashion and cinema industries.

The film industry evolved pretty much alongside the growth of the field of psychology - do you think film is a space where we can tap into the collective unconscious?

The film industry and psychology have developed in tandem, influencing and mirroring societal attitudes and contributing to the enhanced understanding of human behaviour through extensive psychological exploration in movies. Film and psychology evolved together from the late 19th century, and its influence can be traced in the work of directors like Alfred Hitchcock, who integrated Freudian idea’s themes in his movies. Lars von Trier's work often challenges conventional storytelling, incorporating psychological depth and symbolism, contributing to the intersection of cinematic artistry and psychological inquiry. This kind of exploration of psychological elements in film not only entertains but also mirrors and comments on the human condition, making cinema a potent medium for delving into human psychology. To me, films serve as a dynamic interplay between reflection and shaping of communal dreams, aspirations, and cultural narratives. They create a shared space for exploring the intricacies of the human experience, fostering connection and understanding. Filmmakers utilise cultural archetypes, symbols, and universal themes rooted in storytelling structures and myths, resonating across cultures and addressing shared human experiences.

I tend to think of Doesn't Exist as an art object/book more than a magazine – would you agree?

Many modern magazines have embraced unconventional formats, exploring innovative designs, content presentations, and enhanced reading experiences. In the case of Doesn't Exist, whether it is perceived as an art object, a book, or even a magazine is entirely subjective and depends on how readers assimilate it. From my perspective, it represents a project fulfilling a void in the market, guided by the interconnected realms of cinema and fashion. Doesn't Exist transcends disposable information, aiming to be a source of inspiration that resonates within the realms of creativity and beyond. My inspiration for creating Doesn't Exist stemmed from a series of works embodying this cinematic sensibility, including images by Peter Lindbergh, Guy Bourdin, Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Alex Cayley, and Helmut Newton. Additionally, costumes by Amy Stofsky for David Lynch’s 'Wild at Heart' (1990) and Jean Paul Gaultier's contributions to Peter Greenaway's 'The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover' (1989), profoundly influenced my vision.

Why does Doesn't Exist employs the language of fashion to respond to film?

Doesn't Exist c employs the language and visual elements of fashion to engage with cinema, responding directly or indirectly to films. I integrate cinematic aesthetics, themes, or specific scenes into the editorial content. Conversely, I also infuse cinematographic language not only into the layout, but also into the fabric of fashion itself. Recognising that the industry often adheres to specific representational norms, I challenge this by bringing cinematic sensibilities into the realm of fashion. This approach may be subjective, considering the inherent artificiality of both mediums; yet, the debate persists, with cinema displaying a certain inert anti-naturalness, mirrored in fashion poses. In essence, I use the language and landscape of fashion to respond to films, employing diverse creative and editorial strategies that foster a vibrant and dynamic relationship between the worlds of cinema and fashion.

What have been your favourite issues of Doesn't Exist so far, which directors have you most enjoyed exploring and why?

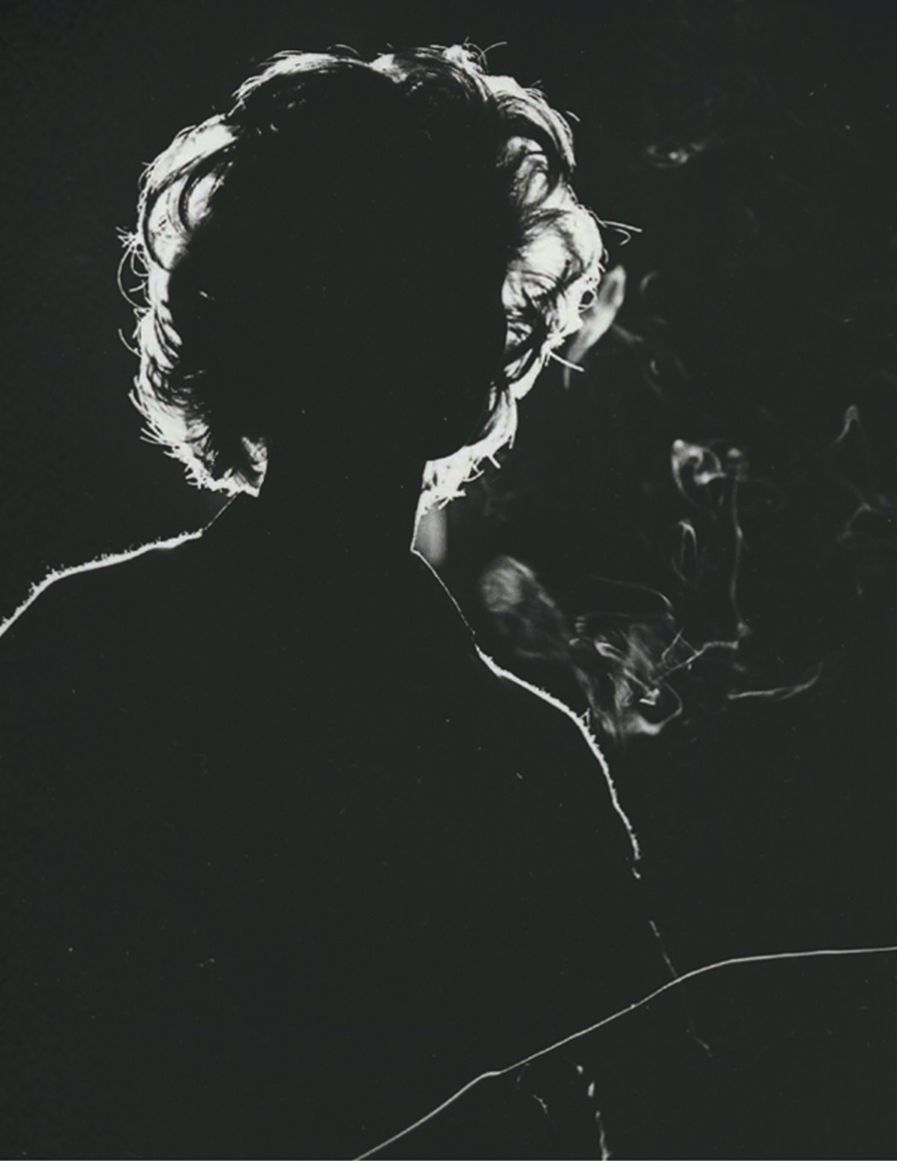

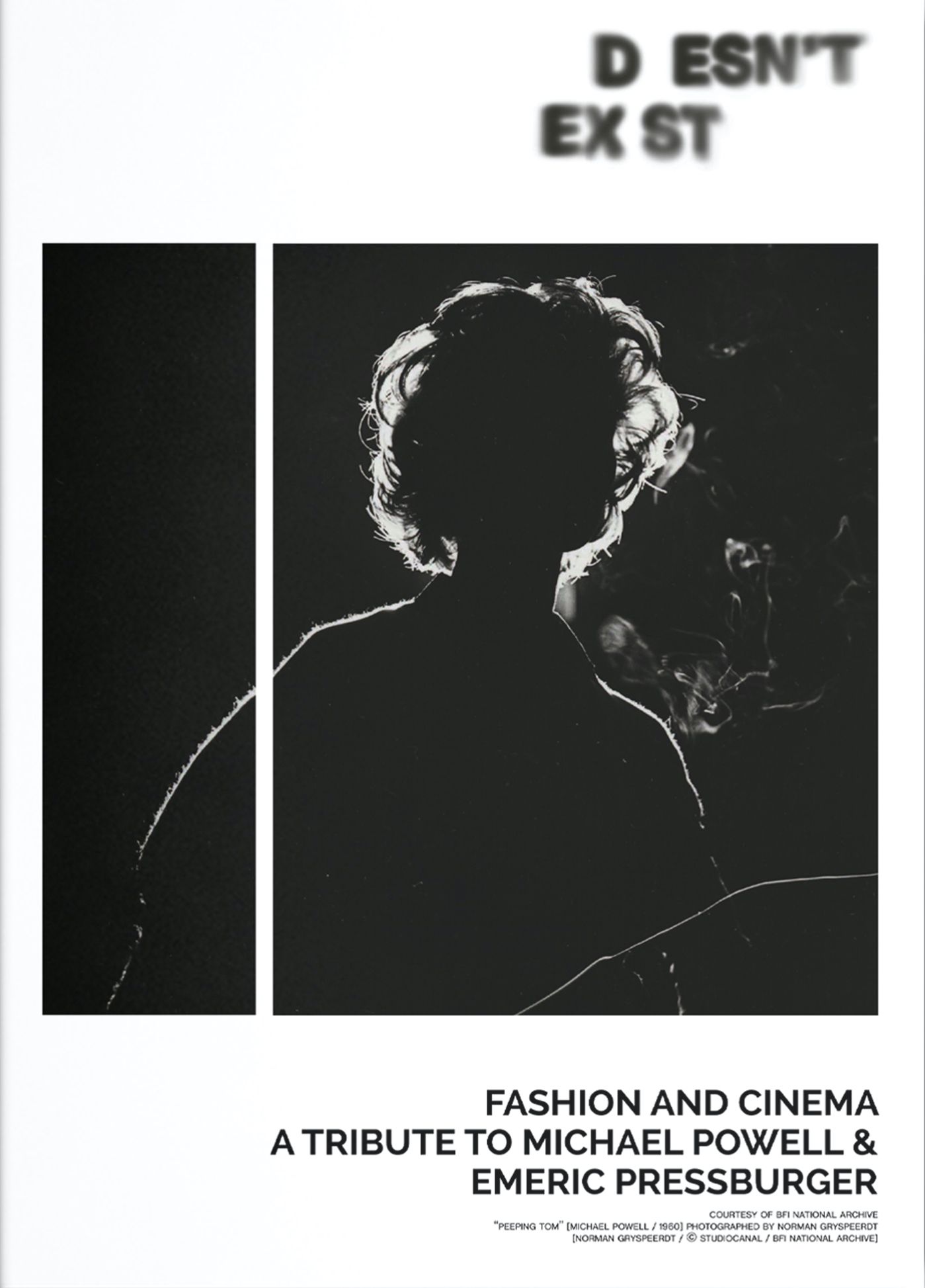

While it's a common sentiment to highlight the latest work as the most intriguing, I must express that my preferred issue is indeed the most recent one: Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. This issue was done in partnership with the British Film Institute (BFI), and the experience of working closely with them added a unique dimension to the content creation. The collaboration extended to image curation, archival access, and engaging interviews with Professor Ian Christie, Sally Potter, and Mark Cousins, which proved to be truly fascinating. In many ways, this edition solidifies the inherent DNA I am instilling in the publication—a fusion of fashion, cinema, and art, cultivated through ongoing partnership. And in this case, with the BFI.

Who do you think is at the forefront of contemporary alternative filmmaking and why?

Revisiting the films of Joanna Hogg, Lucrecia Martel, Mia Hansen-Løve and Kelly Reichardt reveals shared thematic and stylistic elements despite their diverse cultural backgrounds and cinematic traditions. All four filmmakers excel in intimate character studies, delving into inner worlds, emotions, and relationships with an observational and introspective eye. A strong connection between characters and their environments characterises their works; Martel explores the impact of surroundings on lives, Reichardt depicts characters navigating natural landscapes, Hansen-Løve emphasis on depicting the intricacies of human relationships and the passage of time, and Hogg examines the relationship between characters and their living spaces. Minimalism in dialogue, emphasising unspoken moments and visual cues, plays a crucial role in conveying emotions and narrative progression in their films. Hogg, Martel, Hansen-Løve and Reichardt share a cinematic patience that allows scenes to unfold at a natural pace, contributing to the immersive and contemplative quality of their films, an attribute that I particularly admire.

Find out more about Doesn't Exist here