The sexual anthropologist Betony Vernon has devoted her life to the emancipation of healthy and unfettered sexual pleasure, whether via her luxury line of sado-chic treasures, her celebrated cerebral erotic tome The Boudoir Bible, or in personal therapy sessions that engage the body to heal the mind. Until just a couple of years ago, these one-on-one sessions would take place in her near-legedary underground atelier EDEN in the Marais district of Paris, but EDEN has now closed its doors, and this summer Vernon unveils a new invite-only sanctuary for sensual experimentation in her new home in the Roman countryside. It’s a move that has coincided with the release of Paradise Found: An Erotic Treasury for Sybarites – a beautiful book that celebrates 30 years of Vernon's photographic collaborations with the illustrious likes of Nick Knight and Ellen von Unwerth. In this rare interview with Culture Collective, the masterful writer, muse and erotic jewellery designer discusses the importance of sexual intelligence, opines on the dangers of censorship, and tells us why embracing solitude can provide the kernel of creative genius.

Your work is known and respected all over the world, what does travel mean to you?

I love to travel, and I have a global extended family I work with around the world. Travel is adventure and newness – it opens our eyes and allows us to truly see. It’s also about going home, of course, and I think that the notion of home has had a whole new meaning in recent years. I mean, I've always insisted on living in a place where I feel happy, and I think that has got to do with the brain needing newness, and our eyes having new things to look at, and experiences to absorb. I was actually living like a nomad as we came out of the pandemic, and I really got that down to a fine art – having a portable wardrobe that would work for everything. I tend to travel for long periods also – for instance, when I go to the States, I normally stay four-to-six weeks, and I don't just do New York. I do New York and then I do LA, and sometimes LA extends into San Francisco, depending on what is happening. I don’t believe in taking short trips that are terrible for the environment. We have to be so much more considerate in the way we move around, to lessen our carbon footprint – not just go bouncing back and forth. Now that my home country is Italy, again, I witnessed how positive the stop on mass-tourism during the pandemic was for the environment – mass package tourism is just super destructive; a Disneyland effect kicks in, and it destroys the real essence of the place.

Yes, you left your legendary atelier in Paris during the pandemic and relocated to the Italian countryside – what spurred that change?

I think that psychologically, the slow-down of the pandemic required us to deal with ourselves, and, even now, I think there's still a lot of mental health issues that actually have not been addressed. Despite all the issues it raised, I do believe it gave us all huge opportunities to rethink absolutely everything that we do. And I felt strongly that the idea of going back to pre-pandemic norms would be a huge error. As a society, we need to get a grip on the fact that growth is not only economical, and start to see how exciting the repopulation of the countryside can be. The return to rural living is happening everywhere, and I think it's super exciting. I believe that in a new economy, in an ideal world, our growth would be based much more on what we're not doing any more – do you see what I mean? Because if we can just go back to the pre-pandemic environmental norms, there'll undoubtedly be something along next – the monsters coming out of the permafrost. I really do believe that the pandemic was a wake-up call. It's our last chance, and everyone needs to make a paradigm shift towards a more sustainable future.

There are certainly a lot more people on planet Earth than at any other time in human history …

Yeah. Absolutely. If you look to the ‘80s, when I was in my teens, there were 3.5billion people globally. It's just incredible that now we are more than 8billion. And while there's just not enough for everybody, we’re also over-producing useless items that make the environmental issues even more severe. I mean, fashion is a really great example because current estimates point towards about 85 per cent of all garments being produced ending up thrown in a landfill. That's absolutely crazy. That is really not okay. And people don't think about it, you know? In my personal life, I have made a radical move to go back to nature, and to the countryside outside of The Eternal City. I had my wonderful atelier in Paris for 14 years, but I felt instinctively that the biggest paradigm shift I had to make personally was to no longer live in a city. I just think it's the thing to do, and I know that I'm not going to be disconnected. I will be a point of connection for people who need to get away from it all and heal.

Do you think the pandemic was an important catalyst in that regard?

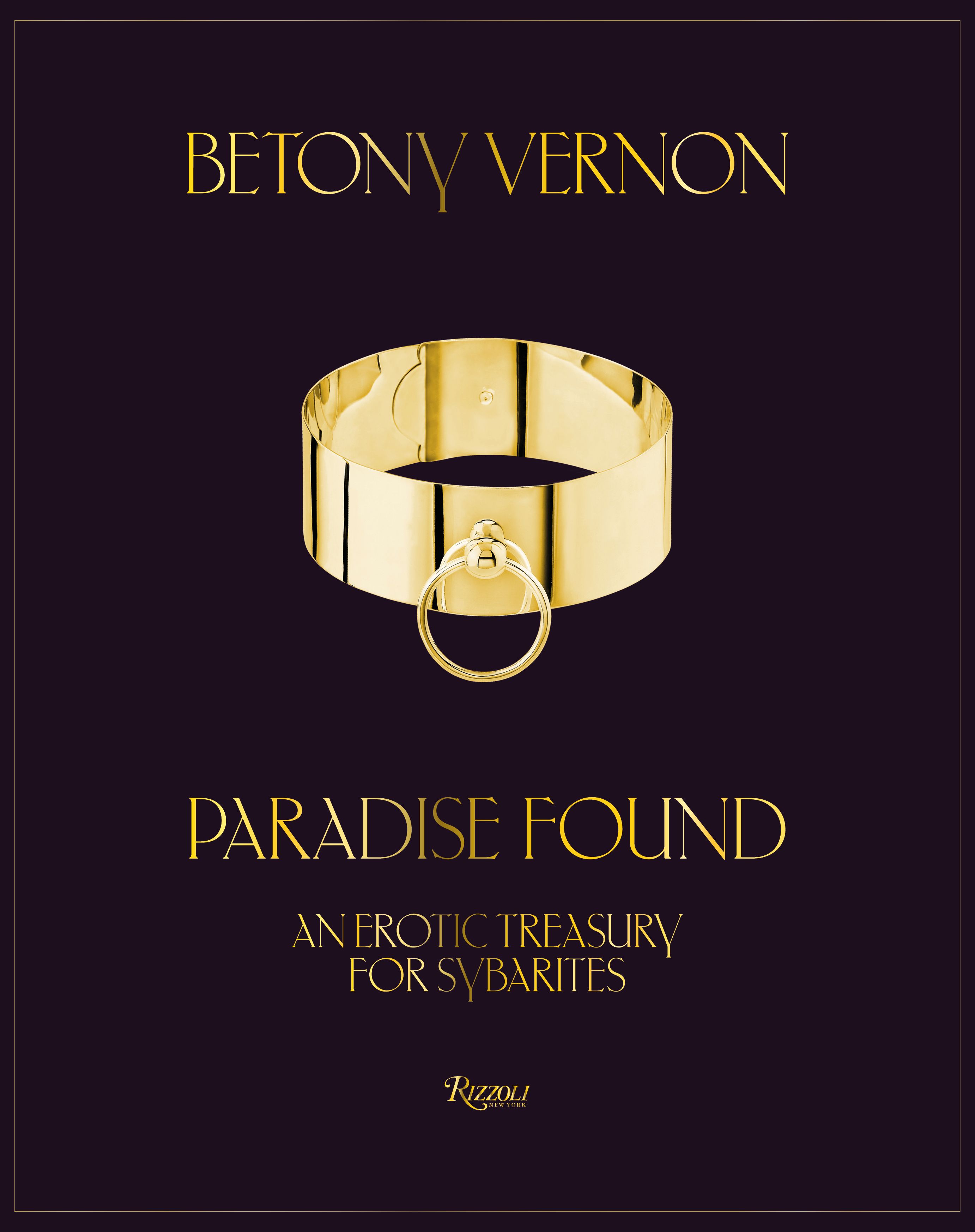

Everything I make almost always starts with a vision that sort of becomes a mission. I think the pandemic helped me understand just how well we can get along with ourselves. In the past, I guess maybe my fear about living in a place that's not a city would have been loneliness. But now I understand that actually to instigate paradigm shifts, and to continue to be extremely creative, we actually have to be alone sometimes. We need to be alone without the noise. It's sort of like what Joan Didion said, which, to paraphrase, was something like, stop complaining, stop whining, and go be alone, and go to work. On a personal level, the space allowed me to work on my anniversary book with Rizzoli, and it feels amazing to be looking at 30 years of Paradise Found. Entitled Paradise Found: An Erotic Treasury for Sybarites, the book celebrates 30 years of collaborations with photographers and illustrators, and it’s principally an image book, featuring the likes of the late Douglas Kirkland, Terry Richardson, Nick Knight, Ellen von Unwerth, Jeff Burton … all of the photographers that I worked with over the years. I like to see this book as sort of like a ribbon around a body of work, and an insight into my design process, whether it is with jewellery, or an interior, or an object. I always used the jewellery to penetrate many different sectors. My aim is to offer the possibility to reconsider that objects for sexual play can also be luxurious.

Has the mission ever changed, or always remained the same?

I mean, it’s about elevating sensuality, and that's where we have always talked about mission – it’s always been about removing shame or taboo. That was where it was way back when I started in 1996. And I guess one of the biggest issues that I still have is projection, because we live in a society that doesn't speak freely about the importance of pleasure in our lives. I think that sexual intelligence is really critical. I am happy because I know my work has in some way sparked a movement – a neosexual liberation movement. And that is so important, because I'm concerned that the digital vehicles which now allow us to communicate have increasingly snuffed out those who speak about pleasure, or the erotic. For instance on Instagram, I have to self-censor to be able to stay present, but I am also shadow banned – so I'm not part of the general feed, you have to know me to find me. Instagram prevents me from growing my community, and this is really upsetting because what I do through my work is help others to build a more gratifying life in general.

Why do you think there is that level of censorship?

I have long asked myself that question in my soul– you know, why is this banned? Why is this continuing? And the answer that I got was that those who have their sexual intelligence in line are powerful beings and that kind of power is not what makes a consumer society go forward. The reason? It’s simple. Our consumer society thrives on unhappiness and when we are disconnected from our sexuality, there is very great unhappiness. In fact, controlling our sexuality is also used to break us – if we consider that over half of women and at least one in three men have experienced sexual abuse before the age of 12 then you can understand why we're living in a broken system. Controlling our sexuality is a way to control us completely – this is why someone like me is considered dangerous. I'm a bad consumer…

What is the tool-kit a sexually intelligent individual can draw on to fight-back against that paradigm?

I mean, we're talking about the body in an image-led consumer society, right? And fundamentally, your sexuality is not an image. Your sexuality is actually the centre of your body, and the centre of your wellness, in my opinion. If we look back at the father of psychology, then Freud even said that most forms of illness and neuroses are coming from a sexual source. And I believe we have never, ever been more sexually repressed than we are today, and statistically people are having less and less sex. There is this woke agenda that can lead to being afraid to approach someone, to be in contact, and afraid to hug and kiss another person, you know? It is setting us back 50 years. So, I almost feel like I have to start all over again. I just believe we have to teach people to fall in love with themselves. I'm not talking about egoistic or narcissistic forms of self-love, but just accepting and loving yourself, and taking real care of yourself– then everything else falls into place. That process requires solitude and not being afraid to be alone, you know? It brings me back to Joan Didion – stop whining, stop complaining, and spend some time on your own. In reality, that's the only way that you can get to know yourself.

You can find out more about Betony Vernon here

Images (top to bottom): Both portraits of Betony Vernon are by Guillaume Thomas; Paradise Found: An Erotic Treasury for Sybarites, book cover, published by Rizzoli; Quinn Linden photographed by Rafael Dubus, from Paradise Found ; Elements of the Paradise Found jewellery collection, photographed by Franck Mura