- Art

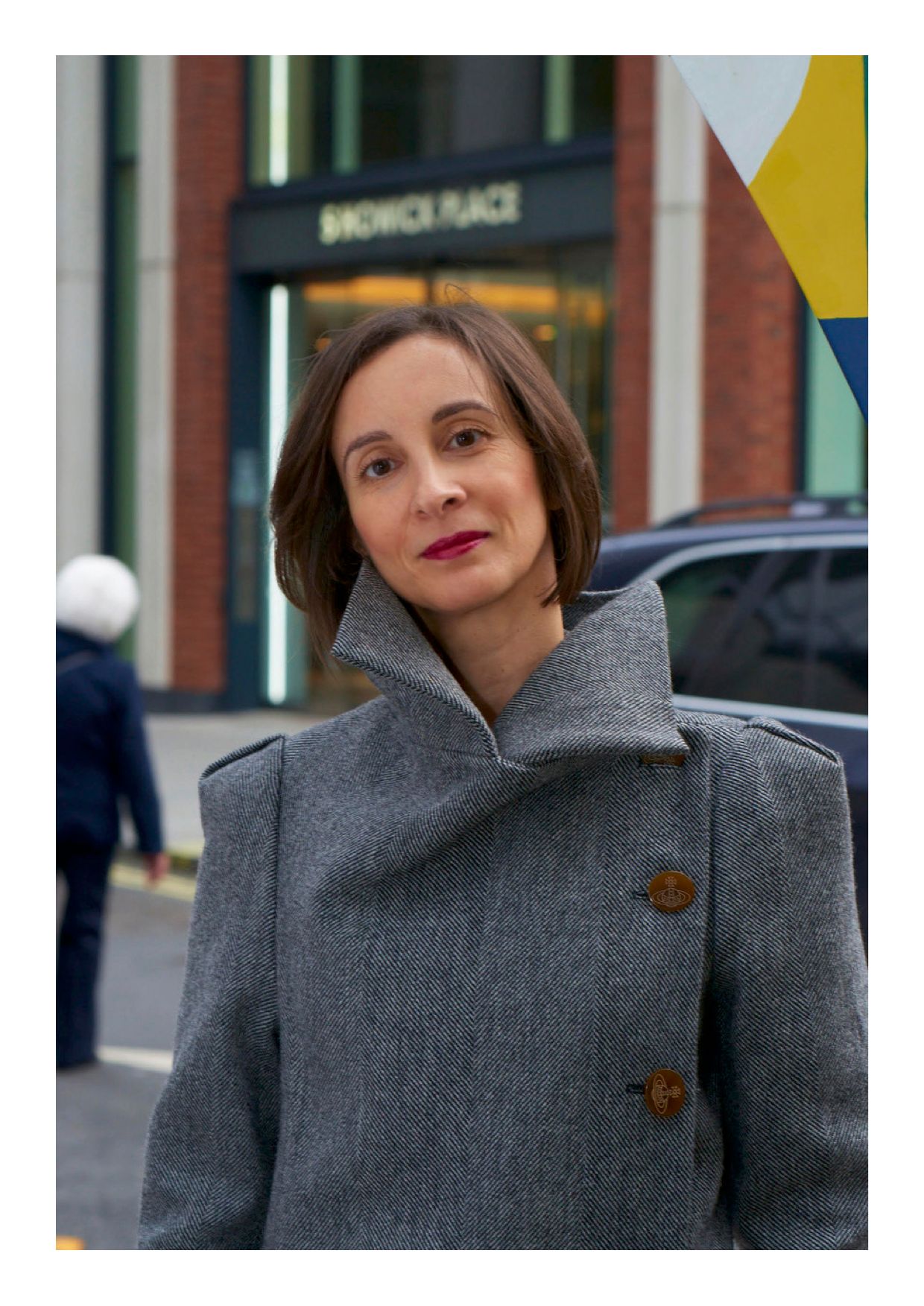

HS Projects is a cultural consultancy founded by curators Alistair Howick and Tina Sotiriadi that has been facilitating artists to make bold uncompromising statements in the public realm for the best part of quarter of a century. One of the most respected incubators for cutting-edge contemporary art in the world, they have always championed radical new voices and delivered ambitious game-changing projects that channel profound ideas to diverse audiences. Whether working on major public sculptures and large-scale group exhibitions, or targeted community engagement projects, their penchant for boundary-defying curatorial skills and creative strategy is second to none. Here, co-founder and director Tina Sotiriadi gives a rare interview to Collective Culture about creating public interventions with socio-political impact, harnessing the zeitgeist, and the challenges the digital age presents for meaningful connection with art…

What would you say is the core ethos of HS Projects?

We like pushing boundaries, giving young artists a platform and raising awareness of issues, and all of our projects are underpinned by a lot of thought and research to give space to the artists to materialise their vision. We aim to create innovative projects in unexpected places with sensitivity to local interests. Bringing the work of inspiring, talented contemporary artists to communities feels important – working in ways that also allows for input and engagement from communities, so that we can learn as much, if not more, from them as they do from us.

How can a public art commission enhance its local community?

Good public art draws on the social history of the site and the cultural mix of the community, and it provides something that enriches the experience of the place. Back in 2006, we commissioned the permanent piece ‘Tokens' by John Aldus in Bloomsbury, and it is a brilliant example. It evokes poignant memories of London’s great Foundling Hospital, as well as the continuing worldwide themes of childhood abandonment, trafficking and exploitation. Aldus took his inspiration from the poignant collection of tokens held by the Foundling Museum nearby. These tokens, left by mothers to identify their babies in case they were ever able to come back to reclaim them once admitted into the Foundling Hospital, have since become poignant symbols of their hopes and dreams. Admission to the hospital was determined by a lottery-style draw of coloured balls from a sack. Drawing a white ball meant acceptance and a future for mother and baby, whereas drawing a black ball meant rejection – hence the expression ‘blackballed'. The tokens included coins, scraps of ribbon and buttons. Aldus worked closely with the Foundling Museum in translating his inspiration derived from these objects to create ‘Tokens’. Embedded into the very fabric of Marchmont Street, a trail of cast metal shapes, including the three different coloured balls, lie seemingly scattered on the pavement, inviting the passers-by to deeply engage with the tragedy of the time, which still has resonance today.

How do you think the digital age has changed the way in which we experience art?

Well, it is a bit of an ambivalent relationship – social sharing on Instagram can help with visibility, but whether something is 'Instagrammable' should certainly not affect artistic production and curatorial decisions. And what about the art experience itself? Does it stand in the way of a true experience and genuine appreciation of the art, or is it a sign of a different kind of engagement with the work? I often wonder whether viewers are interested in an artwork because of the possibility of a great selfie, or whether it is for the art itself. The long queues at the Yayoi Kusama exhibition at Tate Modern, allowing visitors only one minute to experience her large mirror installations – which have become the most Instagrammable works of art – are a shining example of this all-consuming, narcissistic effect.

How much impact do you think art really has in a wider socio-political context

It is impossible to single out just a few artists who are effective at challenging the status quo, as there are so many. The works of the four emerging Brazilian artists we showcased in our exhibition 'What Separates Us’ at Sala Brasil, the Embassy of Brazil, London took on socio-political connotations in the midst of political turmoil, as the show happened to coincide with the impeachment of the then President Dilma Rousseff, and took place, effectively, on Brazilian territory – in particular Tonico Lemos Auad's sound installation, ‘Desafinado/Out of Tune’, 2003/2008, which was shown in the UK for the first time. Auad recorded a well-known blind Brazilian singer whistling the recognisable Brazilian Bossa Nova ballad Desafinado by Joao Gilberto continuously for several hours. Auad observes the performer’s inhaling becoming demonstrably more demanding, selecting a point where the tune begins to break down. The resulting sound is melodious and melancholic and immediately familiar to any Brazilian, but the pauses charge the empty spaces with a distinct longing. The work became a reflective commentary on the socio- economic situation in Brazil at the time.

What do you consider to be the most successful of your projects to date?

Some of our projects that make me particularly proud include ‘Wind Sculpture’, Yinka Shonibare’s first ever permanent commission in the public domain which is located in Victoria, London and was the starting point of the famous Wind Sculpture series which are now found all around the world. In our exhibition ‘Paradigm Store’ we premiered Beatriz Milhazes’ film ‘Mathematical Paradises’ in the UK courtesy of the Cartier Foundation, Paris, and in ‘Interchange Junctions’ we were also particularly proud to have showcased the work of first-year BA students next to established artists such as Zineb Sedira, Shahzia Sikander, Romuald Hazoume and Rose Finn-Kelcey. But to choose one or more projects to highlight would be unfair. I’m incredibly proud of all our projects and in awe of the artists and their ability to create work. I love what I do, for me it’s not a job – it’s joy, it’s a passion, it’s my life.

Credits (Top to bottom): Tina Sotiriadi, portrait by Sylvain Deleu; Untitled, 2010 Maria Nepomuceno & Sparks, 2014 Nike Savvas, exhibition ‘Paradigm Store’, image by Sylvain Deleu; Tokens, 2006 John-Aldus, public art installation, image by Thierry Bal; Workers (Detail), 2016 Rodrigo Matheus, exhibition ‘What Separates Us’, 2016, Embassy of Brasil. image by Panayiotis Sinnos; Untitled Bed, 2020 Permindar Kaur, exhibition ‘Home’, 2021. image by Thierry Bal