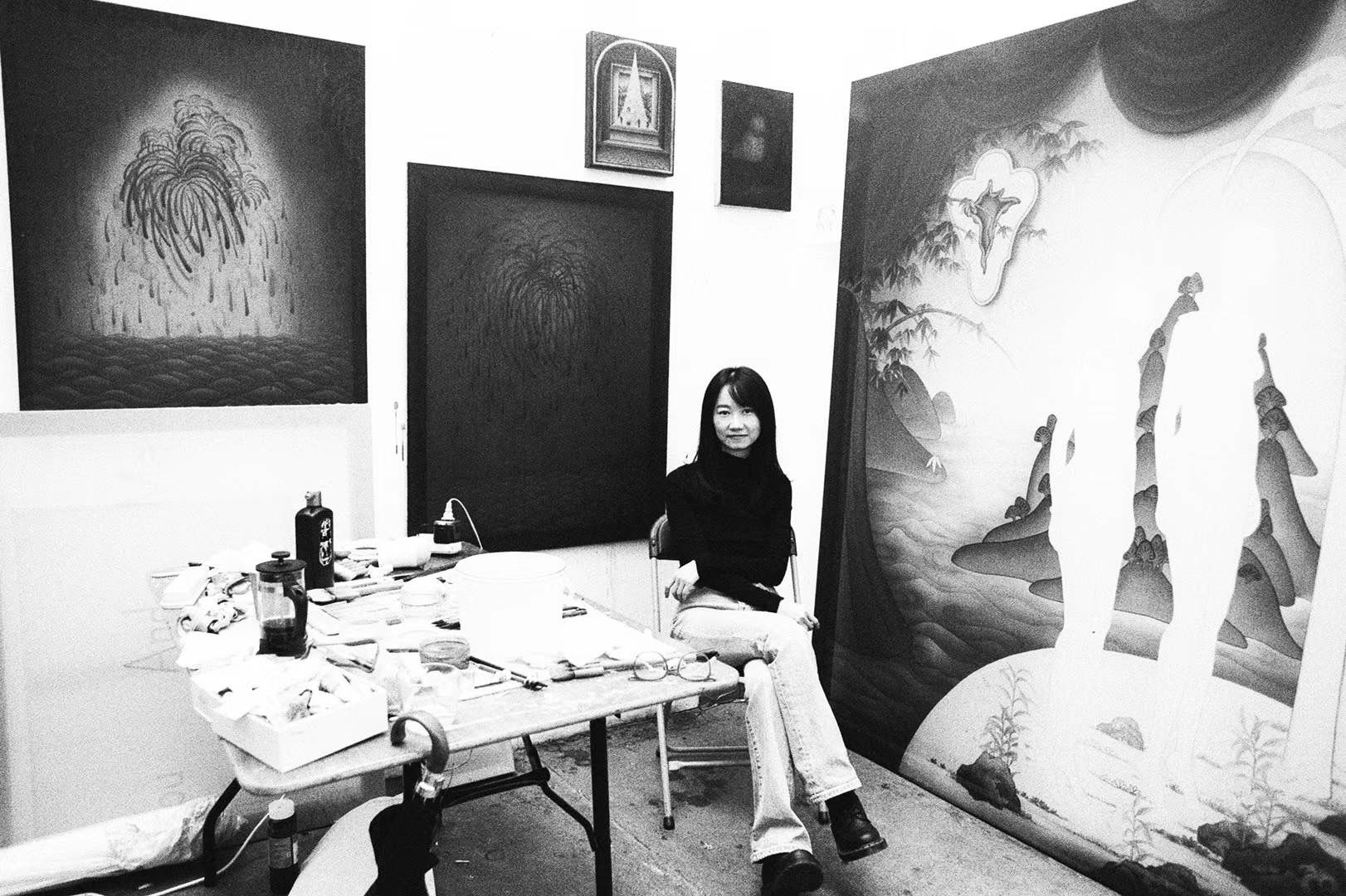

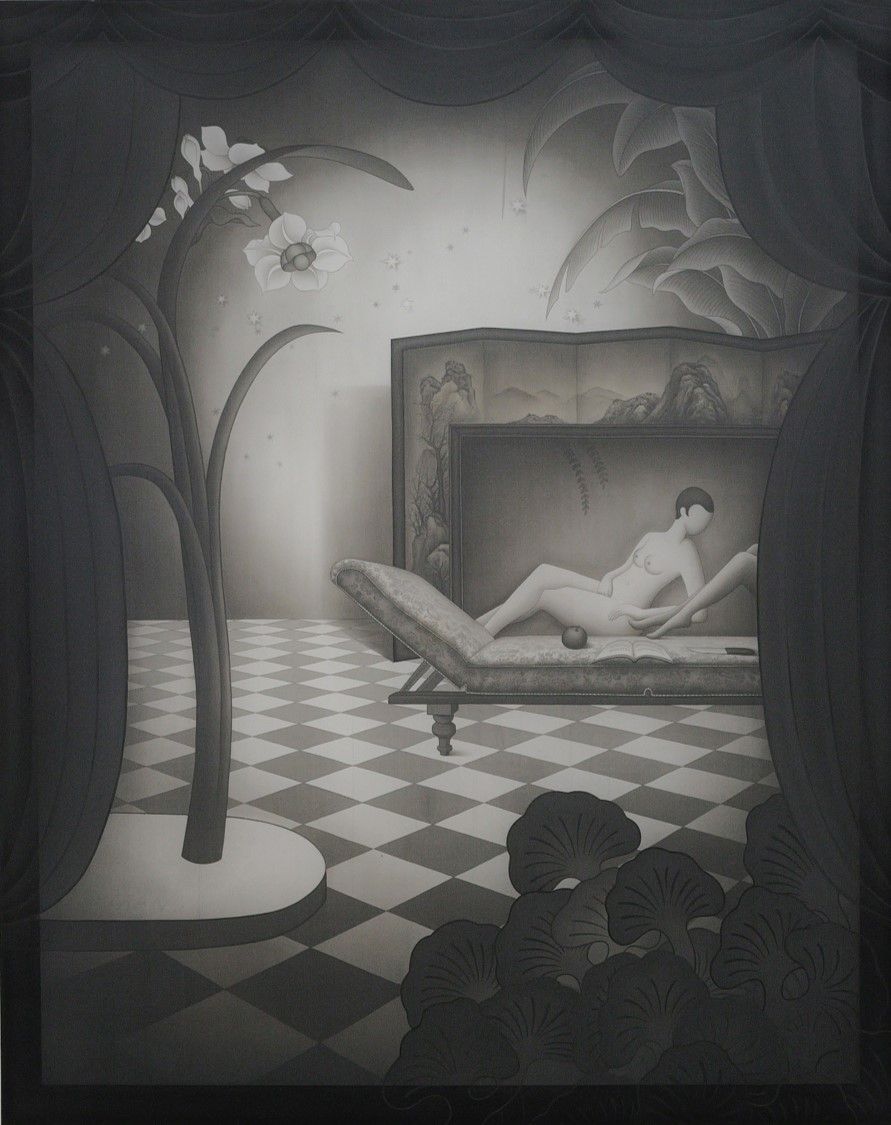

The Chinese contemporary artist Yifan Jiang weaves surreal narratives related to cultural memory via the abstraction of individual images, and figurative characters reminiscent of the style of the Colombian painter Fernando Botero. Inspired by the morays of traditional Chinese painting, The RCA graduate directs a personal theatre in her work that transports us into a vast and secret world, tinged with poetry, and a haunting ethereal quality. Working chiefly in the Gongbi painting tradition, and employing elements inseparable from classical Chinese painting, such as the mountains, the rivers and the sea, the artist shows her desire to evolve in a framework which is attached to her own cultural heritage. However, she is not content with simply revisiting these totems of the past. She also introduces strange and incongruous elements - chairs and microphones placed on the sea, for example - which underpin her absurdist aesthetic. Incorporating traditional Chinese painting elements, myths and literary metaphors, the artist thereby creates an immersive spectacle that resides somewhere on the edge of nostalgia and dreams. Her most recent show at Meeting Point Projects questioned how spaces foster ‘domesticity’, and examined domesticity as a network of intangible and accumulative qualities such as conditioned behaviours, memories, and nostalgia. In this interview with House Collective Journal Jiang takes us on a journey into her process, postulates whether reality is a dream, and tells us why she believes all art is essentially narcissism.

Can you recall what first drew you towards the path of the artist in life?

I don't know. When I look back, there were so many small things that happened that led me to where I am now, but I don't know which one was more important. Maybe it was when I was a child, reading a magazine called Little Artists, and then I used painting to overcome my fear of being alone at home throughout the summer vacation; maybe it was after adolescence, when someone very important to me left me, and I felt that there was nothing to look forward to in my life, my teacher made me feel that I was a very talented person, and then I wanted to use that to prove myself; maybe it was when I felt that I had a seemingly perfect life, but I was not happy with it, I had to use something to pierce this false shell.

Talk to us a little about the process and technique of Chinese Gongbi painting – what is its history?

Gongbi painting requires that you cannot correct mistakes, delete or cover. The only thing you can do is to adjust by adding. It is very similar to my attitude towards my life. I do things carefully and plan carefully. If a mistake happens, I can't deceive myself or cover it up with other things. I can only do something else to make the 'wrong thing' look right. Now I hope I can learn to accept that 'mistakes' are always bound to happen.

Which artist most inspires you and why?

No one, actually. I try not to get too hung up on other artists. I can’t do that either. I have many favourite artists and painters. I admire them, but I don’t think they inspired me a lot. Some writers inspired me. One is Liu Yu, a Chinese writer and political scientist; another is Eileen Chang, a great essayist after World War II, and the mysterious Italian novelist Elena Ferrante. They are women with wisdom and freedom of expression. Perhaps for me, one has willing, power and wisdom to express is too strong and too desirable. At times, I was eager to say something for myself, I was trying to say it well. They showed me what it's like to be able to say something and say it well.

Can you speak to us about the Chinese myths and literary metaphors we might see in your work?

It is very interesting that classical Chinese literature sometimes confused dreams and reality. At the beginning of classical novels Dream of the Red Chamber, it said that this was just a dream. But it was a story of a great Chinese family in the mid-18th century with wealth of psychological realism and historical detail. Same as The Sing-song Girls of Shanghai, a novel published earlier than Red Chamber. The author says at the beginning that the protagonist thought he was awake, which means it was just a dream. In the most famous of all Zhuangzi stories 'The Butterfly Dream', Zhuang Zhou didn't know if he was Zhuang Zhou who had dreamt he was a butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming that he was Zhuang Zhou. Zhuangzi considered there must be some distinction between Zhuang Zhou and the butterfly. Sometimes I seem to give up on finding that distinction, if it would make me miserable to distinguish between fantasy and reality; if we are not sure whether life itself is just a dream.

Talk to us about the works you have in the exhibition Dwelling, what do they represent?

The work I have in the exhibition is what I thought at some point in time. I made Dream of the Red Chamber was when I first arrived in the UK and started studying at the RCA. I found that the world of language and culture that I was familiar with was shrinking, and a new foreign culture surrounded me. Why did I choose this literary masterpiece as the title of this painting? I think it may be because I feel deep in my heart that it can support my spiritual strength. Another work, 'God Please Bless My Father', was the last one I made before leaving RCA. My father was in a very bad state during that time. I was also in a very helpless and sad situation. The actual situation at that time was chaos and self-contemplation of family relationships and origins.

What for you is ultimately the purpose of art?

I think art is the ultimate narcissism of human beings. Humans are so obsessed with themselves, and consider their feelings and lives are so important that some people called artists must record them, keep them in history and on this planet. I am also a human being, so it is inevitable for me to live in such huge narcissism. And I may be more narcissistic and arrogant than most people. I hope my art can truly benefit others. I try not to have any expectations about what the audience will take from my work, though. In the past, I expected that viewer would find that I was making a very groundbreaking painting attempt. I hope that the viewer can see the charm of Chinese art and its possibility of integration with different cultures. Now I want more.

Find out more about the artist here