Slade School of Art alumni Alexi Marshall weaves contemporary folkloric narratives that employ ancient drawing techniques and embroidery to explore arcane spiritualism, bold sexuality and the vagaries of modern womanhood. In the strange, sometimes gruesome, scenes she creates, lines, bodies and worlds fold into each other to create wildly theatrical tableaux that invite the viewer in a netherworld of subverted archetypes. Working chiefly in materials that have their roots in artisanal traditions that are often viewed as feminine, she portrays characters that seem to dance between the divine and the profane, drawing on mythologies at the heart of our shared consciousness. It’s a universal symbolism she has developed via art residencies she has undertaken all over the globe, where she absorbs various mythologies in her transom. Marshall was selected as part of Bloomberg New Contemporaries on her graduation from The Slade in 2018, and has already won numerous awards, including the Boise travel scholarship and Antony Dawson print prize. In her latest show, Marshall uses the eel’s journey as a metaphor for our cycles of existence. Eels spend years buried in the mud before returning to the sea to spawn, a mysterious process that echoes our innate desire to return to our roots. Nostalgia for the Mud captures this journey, reflecting on time, phases of life, and the murky depths of the subconscious. Here, the inimitable young artist takes us on a journey into the conceptual genesis of the show, and tells us why she believes the human spirit is corrupted by the consumer capitalist machine.

Can you recall anything in your formative years that was fundamental in setting you on the path of the artist?

I was an incredibly shy child who lived in a world of make-believe and fairies. Much of my childhood was spent on my best friend's farm, where we played for hours in a particular small patch of woodland. This magical place had a whole town infrastructure, complete with an airport where the fairies would hitch rides on birds, a town hall, and a lake; all completely imaginary. For years, we played there without any dolls or props, entirely content with only the trees for hours on end. We named it Little Puddingdale. Reflecting on those hours spent world building in the imaginary, but driven by narrative, I realise that I am still interested in creating worlds today, and still fascinated by the magic found in myth, nature, folklore, and art.

What is your process like?

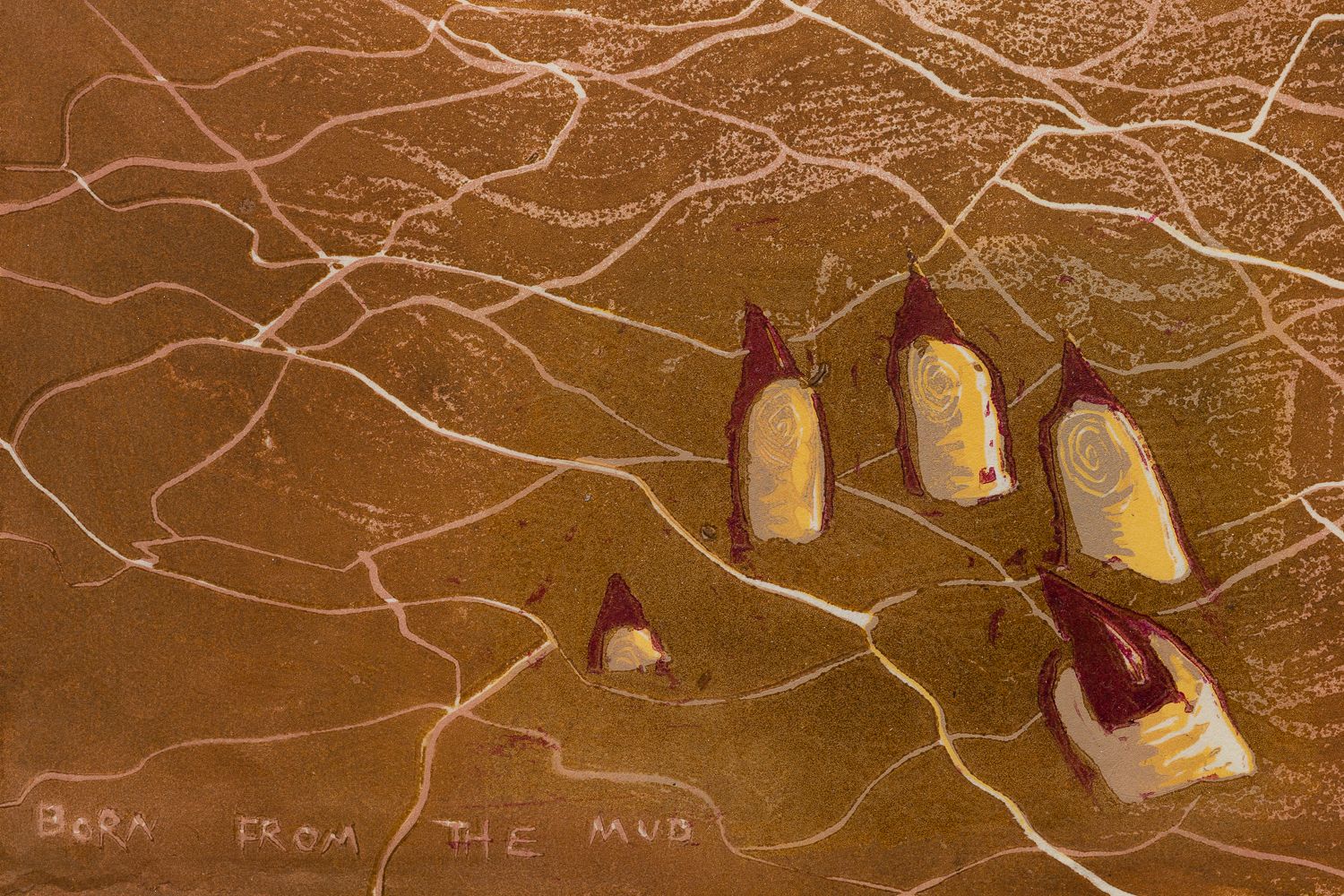

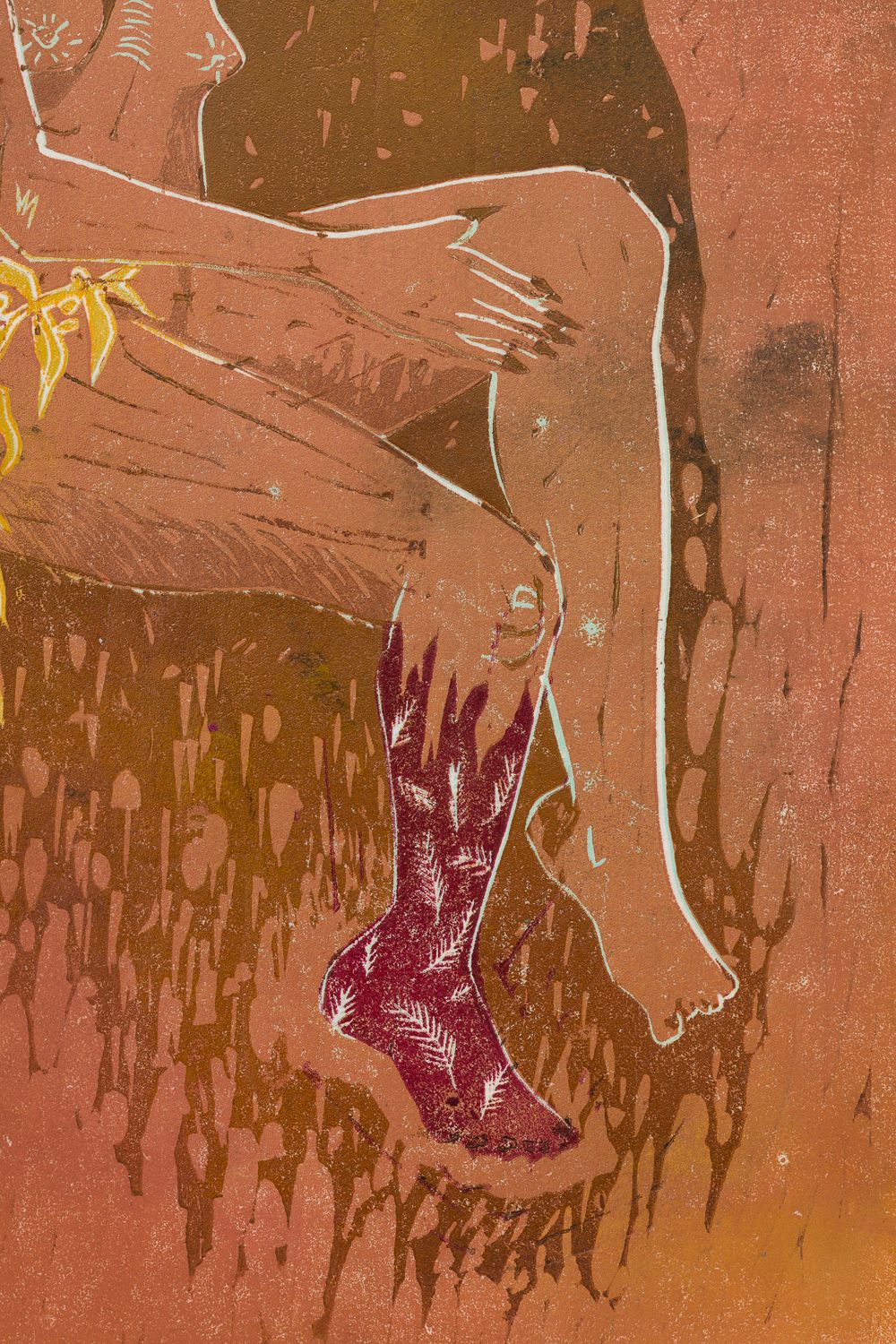

I make linocut prints on a large scale, but I don't have the skill, discipline, or equipment to be a traditional printmaker. The prints are one of a kind, so I call them lino-paintings. They are made up of multiple layers of ink from the same block, printed over and over again until the block is no more. It reminds me of sand mandalas in that way – the material is destroyed in its making, but the ghost of it remains in the lino painting, and that becomes the piece shown to the world. The hollowed out lino carcass is then discarded.Instead of a printing press, I use my body to print. I want things to feel raw, from the earth; flaws and all, embracing scuff marks and fingerprints. As well as being printed using the body, the works often have bodily subject matter too – figurative, and often featuring a bloody colour palette with lots of reds, browns, fleshy yellows and pinks. Characters and motifs reappear, some with assigned and deliberate meanings, while others just appear because I want them there, and in those instances, I trust the flow. Not trusting the flow would block it.

What are you seeking to express in the act of creativity?

For me, trusting your creative intuition and just ‘doing’is a form of channelling something higher, whether that be something other or just a higher state of creativity or consciousness. When I try too hard to come up with a design, I know it isn't working. The best ones come out right away. They've often been living in my head for a while, months even, existing as a platonic form in my mind. Once the design is out in the material world, it's a scribble, then a drawing, then and a watercolour – and in its last iteration it is drawn onto lino with charcoal, cemented with felt tip and then a time-intensive, laborious process begins to make the lino-paintings. This involves carving and printing the block in increments using the reduction method, layering up thin Japanese paper with colour from light to dark until the final layer (usually black) signals the end, the completion.I'm often told that the work belongs in the same world. I like the idea of world building. I’m interested in the human experience and depicting that – womanhood, the sacred, the earth, pain, healing, the collective, the beyond, the unknown.

Where would you say your ideas stem from?

My ideas come from life – my experience. I feel things very deeply, and I use that as fuel to create. Emotional alchemy, I transform experience into story into the visual. I have always been in awe of women, womanhood, the sacred, and the divine. I grew up Catholic and remember always thinking as a child in mass, being shocked that ‘women priests’ were not a thing, the injustice of it all, and why wasn't anyone doing anything about it? Why was divinity only in the hands of men when everything about life and nature shows the opposite? In my work, I often blend an archetypal story from myth, folklore, and religion with what I am experiencing and how I see the world, and there it becomes a story, for the way I see the world can be the only truth I know. I think of the artist like St Lucia, offering up her eyes on a plate. In the recent show, it wasn't folklore at all as a starting point but the natural world – the life cycle of an eel. I use something that already exists – a myth, a story, and a life cycle – and then use it as a basis for making new connections, and creating metaphors and symbols.

How do existential concerns play out in your work?

Most people would agree that there is a lot more to life than what we can currently explain. I feel a great sense of wonder, awe, and excitement when moments arise where the true unknowable nature of the universe reveals itself, and the mysteries of life are brought to the surface, even if just for a moment. As Socrates once said, ‘All I know is that I know nothing.’Since I was a teenager, my work has always been drawn to the same core themes: life, death, and rebirth. I think a lot of that has to do with dealing with the hardships of life and then spiritually, mentally, and emotionally 'rebirthing' oneself. But, of course, I am also thinking about the nature of being and what lies after and before. I think I have traits of being omnistic; I believe there are truths and wisdom to be drawn from many belief systems. There are patterns and connections, reappearing symbols and motifs that tell an overarching story cross-culturally and the archetypal stories that have played out since time immemorial is a reminder of the interconnectedness of humanity.

Tell us about works in the Brooke Benington show....

The new show at Brooke Benington is called ‘Nostalgia for the Mud,’ and I was inspired by the life cycle of the eel (Anguilla Anguilla). The eel has a very enigmatic and mysterious life cycle and was also a significant part of English society for hundreds of years. They were one of the country’s main food sources and were also used as currency—you could even pay your rent with them. Now, they are critically endangered. The mysterious nature of the eel has dumbfounded great minds throughout time, including Aristotle and Freud, who tried in vain to solve the ‘eel question’: where do eels come from? To this day, we have never seen eels mate in the wild. The answer is fascinating: all eels are born in the Sargasso Sea and make an epic journey to the rivers and mud of Europe and America before returning to their birthplace. Their biology changes drastically along the way. The riddle of the eel’s life cycle and their journey reflect, to me, that of the human soul. We are all born from the void and to the void we shall return, but not before undergoing physical, emotional, and spiritual metamorphosis. Thinking of eels as the human spirit in this metaphor—the way that eels were used as food, then currency, and even rent reminded me of the corruption of the human body and mind under capitalism, and their endangered status in the climate crisis.

The subject matter of the work often seems dark. Do you believe it is only by looking at the darkness within ourselves that we can evolve and transform?

Some people do have that reaction to my work. I am never purposely trying to make it dark, but I know it can come across that way. I have always been attracted to the dark, the underdog, and the misunderstood. There is beauty in darkness. I am a big horror film fan; I love the rich, subversive, fertile nature of the genre. I think the only way to grow and evolve, as a human is to inspect that darkness inside us, whether that is trauma, memory, and parts of our being – whatever. There is a piece in the current show that speaks to this idea called ‘Stuck in the Mud.’ A couple of years ago, I came across a medieval illustration of a mandrake and noticed it was attached to a dog via a chain. Dogs were used in olden days to pull out mandrakes because, due to the plant's humanoid shape, it was thought to let out a scream that would kill if heard. This intrigued me as dogs or wolves are a recurring motif in my work. There is a character in my work called the Loba – a girl riding a wolf. Sometimes the wolf has human hands. For me, the Loba is a symbol of the civilised veneer and the primal nature within us all, the conscious and the unconscious, ego and shadow. With this symbolism in mind, I thought of the dog (the shadow self) pulling out the mandrake from the mud, like trauma from the subconscious. The dark things we bury deep must be looked at, inspected, and understood for us to ultimately heal, grow, and be free. I wrote a text that was included in the piece that relates to this idea: “Pull out your mandrakes, rip them from the dark earth, release them from the chasm deep and feel the chain tighten one last time.”

Find out more about the current exhibition at Brooke Benington here