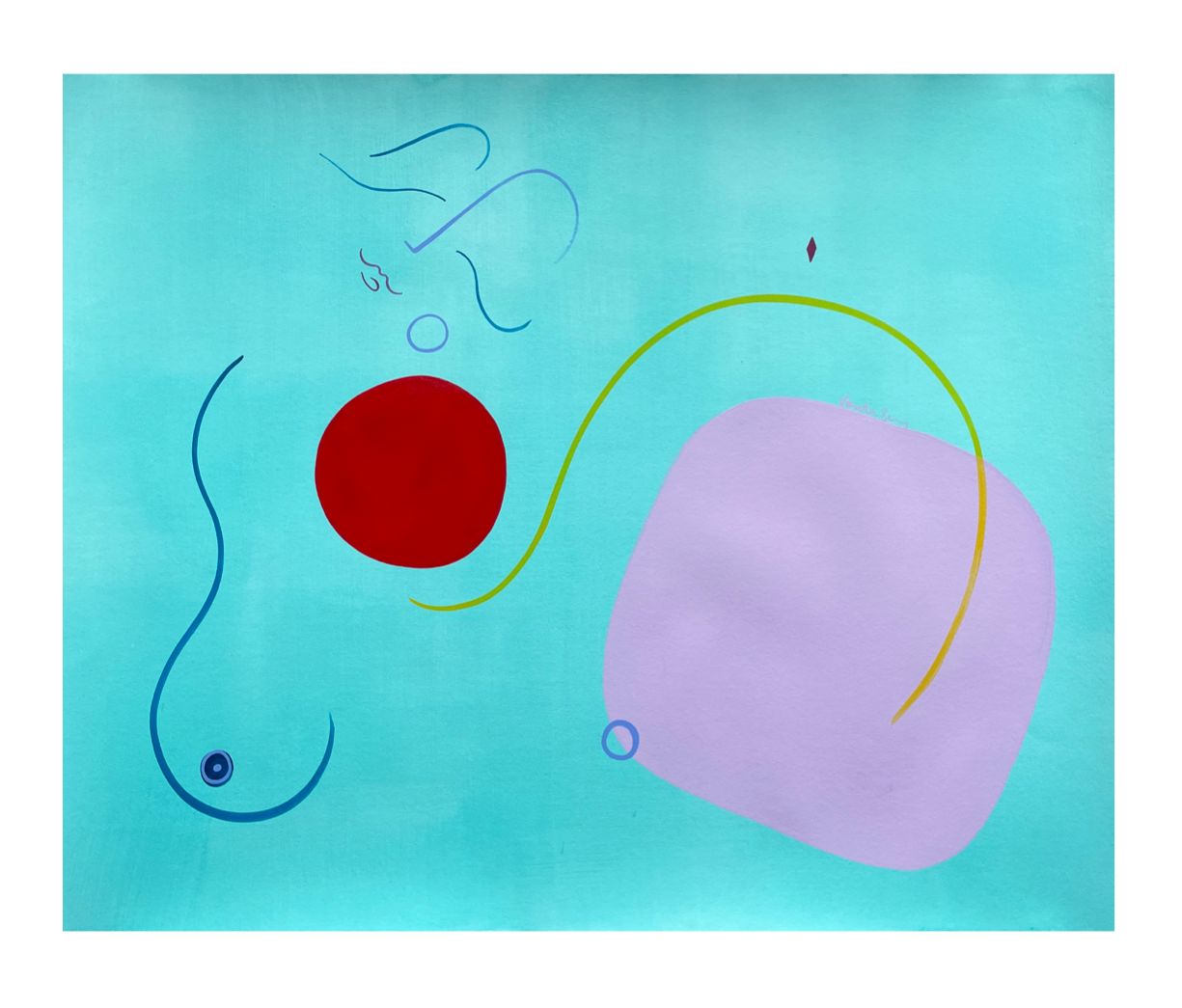

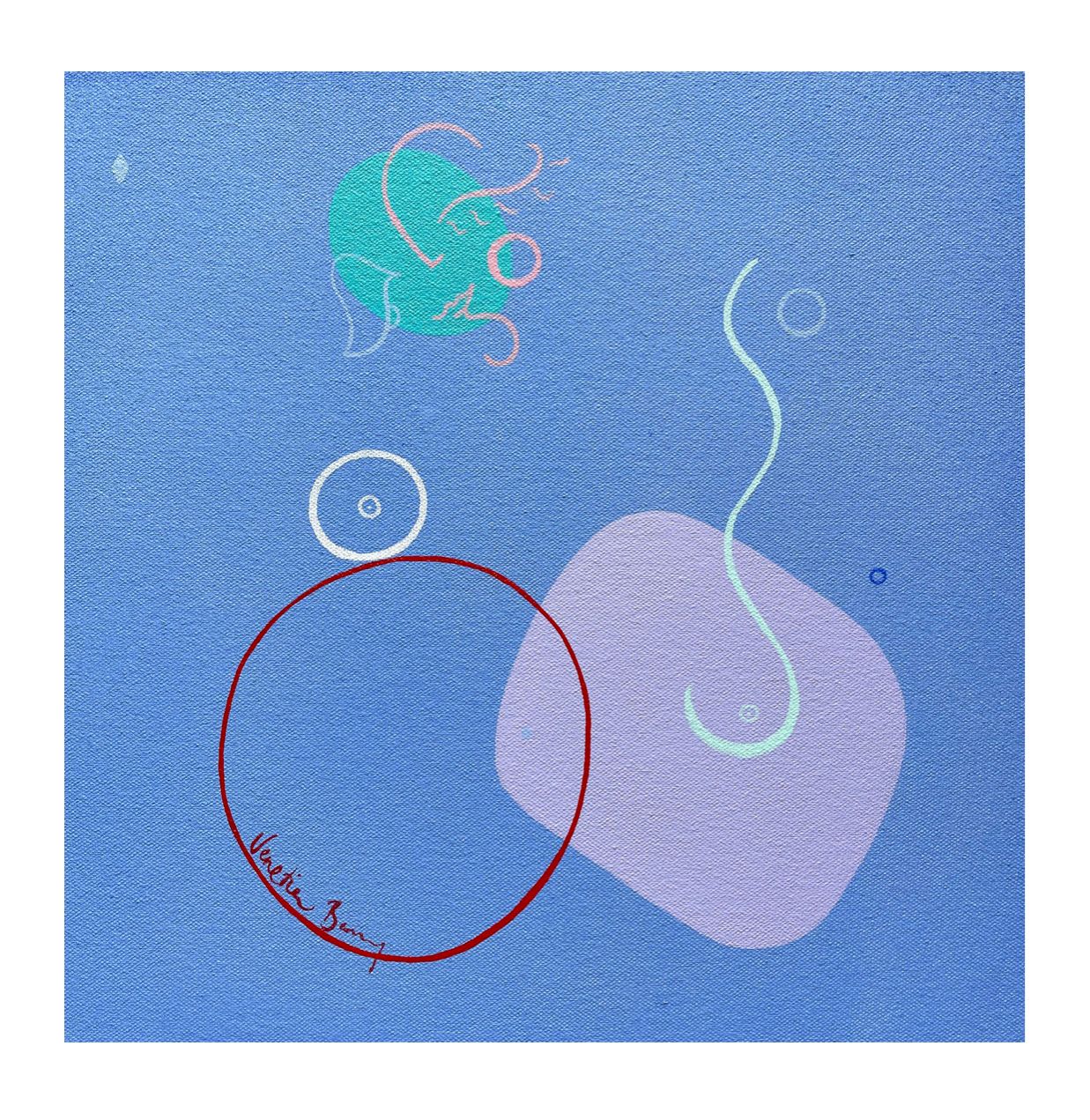

Venetia Berry is a young London-based artist whose work seeks to explore femininity and contemporary womanhood, and her ethereal free-flowing abstract depictions of the female form have attracted the favourable attention of the likes of designer Alex Eagle, who had the foresight to exhibit Berry at her London studio early in her career, The Saatchi Gallery, and contemporary art titans Hauser & Wirth, who invited her to contribute to their Elephant Family group show. The love is more than deserved. The talented graduate of the Royal Drawing School forwards a unique aesthetic that has shades of both Matisse and Miró, without ever feeling expressly influenced by either, and there is something thoroughly modern about her often bright colour palette – which reflects the vivacious and positive personality of its creator. Here, the artist, increasingly recognised as an ascendant star of her generation, talks to Collective Culture about de-sexualized femininity, reclaiming the male gaze and why beauty does not have to be synonymous with a lack of substance.

What would you say are the core concerns of your work?

My work is all based around creating a feeling of femininity, whatever that means to whoever is looking at it. It has evolved from being based around body positivity, or lack of it, which has often been my case, to being focused around mental health and my own struggle to find a feeling of calm within myself. They say that painting is like keeping a diary, and I am beginning to see that now, as certain artworks take me through the different landmarks in my life. The running theme throughout the last few years has been femininity, my relationship with it and also the expectations of it within society. My work is now becoming more and more abstract as I strive to represent a feeling and to bring out a feeling within the viewer. I am intent on creating an artwork with harmony and balance within. I also think I rely on my practice more heavily than I realise for my mental health. One of the main meanings behind my work is to represent my own search for peace within myself. I have tried many different routes to tackle my anxiety, but painting has always been the constant that calms my anxieties and quieten my mind.

How would you describe yourself as a painter? What tradition would you say you are working in?

My route as a painter has proceeded along the very well trodden path of beginning my career with painting from life, and slowly getting more abstract. I started my career working solely in oil paints, which I became less tolerant to as time evolved. I began to have headaches every time I worked from the harsh chemicals involved with oil painting. After a chance meeting with Tracy Emin, she advised me to move onto acrylics, as the quality now is much the same. So I did! And I have been happily working in acrylics ever since, loving the fast drying time, which allows me to work at a pace that suits me far better.

Why do you focus upon the abstracted female form?

I would happily move to another subject, if I had the urge. But I still feel there is so much more to explore when abstracting the female form. As a woman, I have always enjoyed the aspect of reclaiming the female form from male artists of art history. Their work is beautiful in its own right, of course. I just think it is important to show the female body from the female perspective. I have never painted the painting I exactly want to create, which I hope never changes, as otherwise I would have nothing to strive towards.

Who would you say is your greatest inspiration?

Without a shadow of a doubt it would be Helen Frankenthaler. She has inspired me so deeply for years. She was an abstract expressionist and only recently has her work started to receive the critical acclaim it so rightly deserves. She works in large pools of spooling colour – colours bleeding into one another – and she creates harmony, balance and depth within her work. They are often based around creating the feeling of being in nature, and they feel very transformative. I really could look at her work forever. She was the inventor of soak stain, a painting technique where the canvas is unprimed. I have been using this technique in my most recent works and the feeling of the work does feel and look different.

How do you think ideas about beauty are changing?

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. This notion that love and emotion can affect how one sees things fascinates me. Beauty is subjective, and so is art. Something that one person resonates with, another will not. As a typical people-pleaser, it is important for me to take this notion through life and within my work. The realities being that you only have yourself through everything, so you may as well try to be true to yourself in whatever you do. Beauty within art was seen in the past as too ‘feminine’. A woman’s work would be beautiful, a man’s spectacular. Helen Frankenthaler was criticised for making her work too beautiful. After having seen her current show at Dulwich Picture Gallery (on until 18th April 2022), I would agree, but in no way would I see this as a criticism. I think beauty is now being embraced again within contemporary art. Work can be beautiful and still have the same depth of meaning behind it. In my own work, I suppose I do strive for beauty, however, I don’t necessarily word it this way. I strive for balance, harmony, depth, colour, meaning, abstraction – amongst others.

What would you say are your key concerns in your representation of women?

My concern when representing anyone who identifies as female is to feel like I am not trying to push my own life experience onto anyone else. My life experience is unique, as is everyone else's, but I am also very aware that my experience has been overwhelmingly privileged as a cis-gender, white female living in the UK. I want women to be able to look at my work and find something of themselves within it, not the other way around.

How is your practice evolving?

I am currently working on a new body of work for an exhibition. I have been working with soaking and dying linen with paints and inks. This method encourages an element of chance and lack of control, something that is so important to embrace. It can often lead to happy accidents. For these works, I have been abstracting the form further, in the attempt to create a feeling as opposed to directly communicating a shape or body. I would love people to walk away from my work thinking about their view on what it is to identify as female, or what femininity means to them and what that might mean. For example, in the past I have had straight men telling me that my work is very sexual. In fact, it is quite the opposite, I aim to de-sexualise the female form and delve deeper into character. Women have so often been sexualised in the media and art, so this comment is understandable, and also represents the world that said straight men have grown up in. On the other hand, I have had woman expressing to me that my work has encouraged their own body positivity and empowered them.

You can find out more about Venetia Berry here.