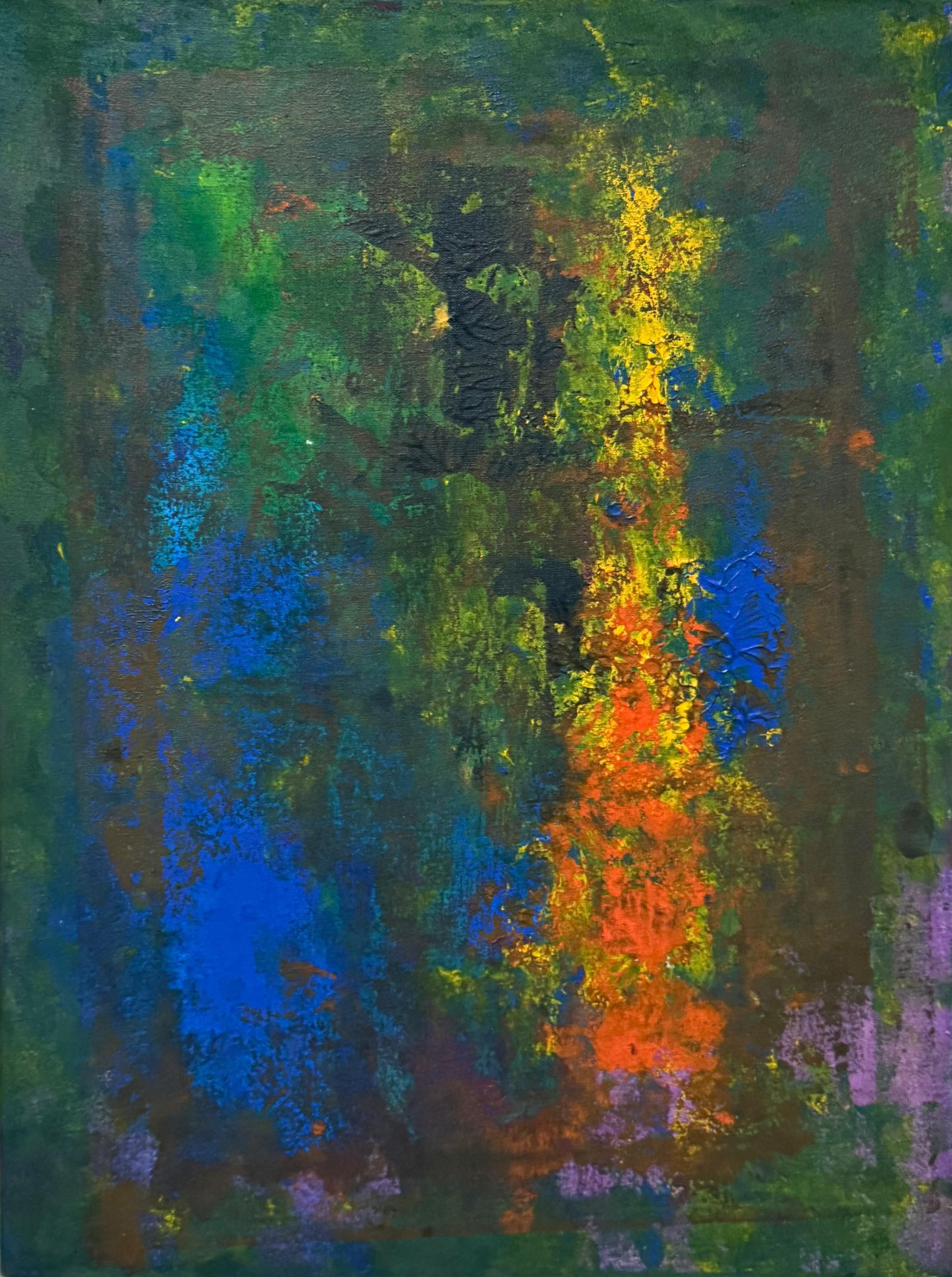

The British artist Winston Branch (OBE) cuts a distinguished figure in the canon of contemporary art, his generation spanning career brilliantly illustrating the profound limbic space that fills the void between thought and expression. His current retrospective at the prestigious Cahiers d’Art, titled The Luminous Gesture, offers a comprehensive exploration of his unique artistic journey, featuring works from the early 1980s to the present day. It marks a significant return to France for Branch, who last showcased his work at the 12th Biennale de Paris in 1982, representing the rich cultural tapestry of his homeland, Saint Lucia. The exhibition invites you to witness the evolution of a visionary, whose approach to abstraction embodies a unique interplay of form and feeling, inviting contemplation through spontaneous, sometimes perhaps even chaotic, gestures. His keen mastery of colour is evident upon every single canvas, all of which are imbued with an emotional vibrancy that invites the viewer to experience the pure essence of being. In this interview for House Collective, the revered septuagenarian, who has work in the likes of Tate Britain and The V&A discusses the genesis of abstract painting, and provides a window into an artist's on-going journey – one that promises to illuminate the paths of those who seek to understand reality, beyond the shadows on the walls of Plato’s cave.

Why as an artist were you drawn to abstraction as a mode of expression?

Well, I think the word abstraction comes from the Latin, and it means ‘taken from’ or extracted from, and, really, I'm always taking from something when I am painting. It’s not about an avoidance of representational painting, but it is about undertaking a process of unlearning, rediscovery and reinterpretation. When you look at lots of paintings, they all come back to one thing – the symmetry and the way it is designed upon the canvas. There is always a fundamental foundation, because, whichever way you put paint on the canvas, there's a lineage of structure. What I have always tried to do is use painting in its autonomy, which means you are not using painting as a vehicle for a certain canon, or as a symbolic language to illustrate a feeling. It is about the purity of the experience – there is absolutely nothing in front of you, except how you feel.

When did you first become aware of that desire for autonomous purity?

It was when I was working in New York. I had won a Guggenheim in 1976, and, for the first time, I was around people who were really dealing with the physicality of painting. At that time, I was trying to move away from the audience projecting their own narrative onto my thing. And, you know, we would all meet and have a drink and discuss why we were painting – were we painting against war in Vietnam? Were we painting against social conditions? What was painting actually about? These were existentialist painters, dealing with the amorphousness of nothingness – for the first time, the narrative was the painting. And that was a kind of turning point, because, up until that time, most painting from the European tradition had been narrative based. It was all about ‘tell me what it's about’, rather than people actually looking and seeing. American painting was confronting all of that with, ‘What you see is what you get. How are you going to deal with it?’

Was existentialism a philosophy that spoke to you all?

Well, you know, I could give references to Jean-Paul Sartre, and the importance of books such as ‘Being or Nothingness’, or Simone De Beauvoir’s ‘The Second Sex’, and I suppose it did feel that there was a moment in literature when there was a place that everybody of a certain age found a common ground. We certainly had a commonality. I don't know if people are reading like that so much today – people tend to talk more about ‘self’ than ideas now. I think, in general, we need to listen more and talk less. I mean, when people said silence is golden, it took me a long time to understand what that meant. But what it means is that we don't listen to each other. If you are having a conversation with someone then the key is to listen to what they say and respond to what they say. But what happens, most of the time, is that before you finish what you are saying, the person you are talking to already has a rebuttal, because they're not really listening to what you're saying – they want to get their point across. You have to listen.

What's your definition of beauty?

I don’t know. I mean, the canon of beauty? I have no idea. The act of listening and reflecting is an act of beauty, in a sense, because it contains a sense of being the most real one can be. I think beauty is probably a moment of intuitively responding to something that you have not yet defined. I have spent long durations of my life by myself with just paint and a piece of paper for company, and it’s always exciting, because I never know where it'll end up. I don't think about existentialist angst when I am painting. I don't think about the world coming to an end. I was a child of the sixties; I was at the protest marches. I've seen it all. I'm not going to pontificate about how the world should be, and should not be. What I would say, though, is that I would prefer people to be kinder to each other, to listen to each other, to try to get a better understanding of each other. Because we are all ‘of the' human race. That's what interests me. We have more in common than we have that defines us as separate. But we like to point the finger and cast the first stone, don't we? To truly embrace what we don't know takes a lot of courage.

Portrait of the artist by Cedric Bardawil. The Luminous Gesture is at Cahiers D'art until May 30th